I insisted on learning as much as I could. In doing so, I would become a thinker, and that meant being worldly. It meant being different. I would wrap myself in my trusty green quilt, and I would pore over every interesting video that was suggested to me. There were some on art and film. Then there were others on music, culture, history, horror… I didn’t watch every single video that was recommended to me, of course. I would instead sift the selection down to a specific few. Finding the best videos meant finding the best channels, and only then did it mean that I could learn something substantial. The hours of poring my screen would eventually lead me to find that one perfect channel on YouTube, one that I would always return to again and again, with a heart full of love.

His videos would start, more or less, the same way – music playing, his voice resonating so clearly, like the voice of God piercing the air of some great open wilderness, images slowly coming into view from a black nothingness – and the only choice you have is the choice of listening and watching. Then, the text would appear. Nerdwriter1. I had come across his video essays by chance, and so, like most things with chance, I had deduced it to be fated. Kismet. The first video of his that I watched, the one where he had explicated Diego Velasquez’s Las Meninas, bringing meaning to every aspect of the painting, down to the bare bones of the canvas, left me with my jaw in my lap.

I was – in short – astounded. The thesis of the idea of the piece, the history of the painter, the subjects in the painting, the recurring theme of threes, the explanation of depth, and the perception of it to the viewer had left me silent with awe. It was exemplary.

Then it got me to thinking: the viewer… the watcher. The watcher… the spectator. The spectator… The voyeur. I didn’t quite understand the concept of voyeurism from the spectator just yet; at the time, I was more focused on the feeling of the things I consumed as opposed to their meaning. That’s not to say I didn’t understand what the word voyeur meant. It just so happened – at least concerning me and my understanding of art and this world – that things seem to always make sense much later. When I see a piece of work, I would frequently ask myself, as I do now: “How does this make me feel?”. Then only would I study the intent, its meaning.

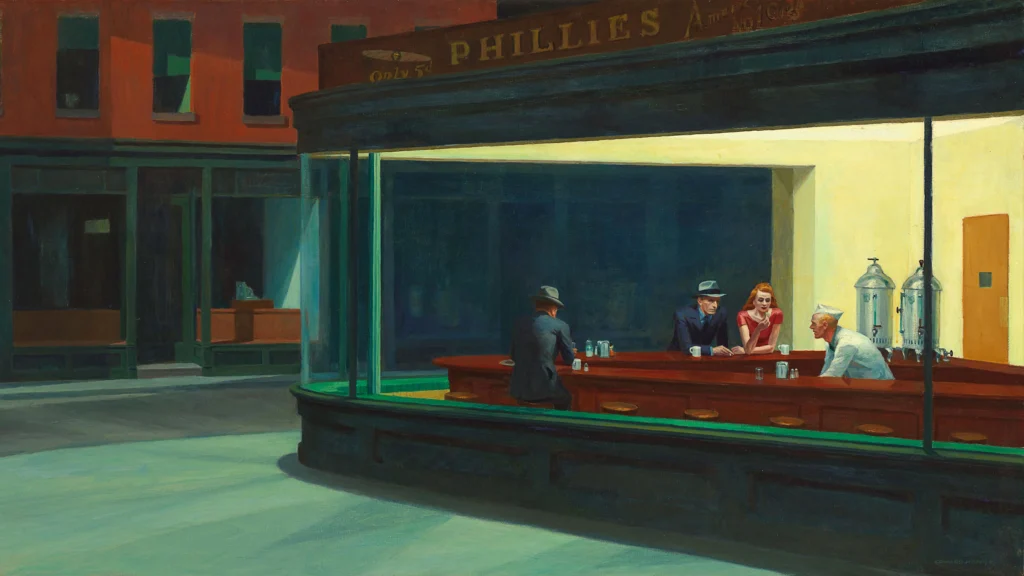

Nerdwriter1’s exposition of Las Meninas had me yearning for more of his ideas. How could I take what I had learned from him and imbue my own ideas into it? After all, isn’t that what learning is all about? Taking what is, and then making it better. The student eventually succeeds the teacher. ‘Tis is life. In digging through his archive, I came to watch his video on Edward Hopper. “Hopper’s Nighthawks: Look Through The Window”, it read on the title. I clicked play.

By the time the video came to completion, I had something blooming in my heart – a newfound love. A newfound interest. It was Hopper. I had become in love with Edward Hopper and all of his works. A realization as such leaves you giddy, lightheaded even.

Other people can make you fall in love with other people and other things. Not falling in love in the literal sense of the word – where you get hitched and settle down and have babies.

But rather falling in love for who they are and what they bring into the world. To fall in love is to teeter between admiration and contempt. The former is a given. The latter is a choice.

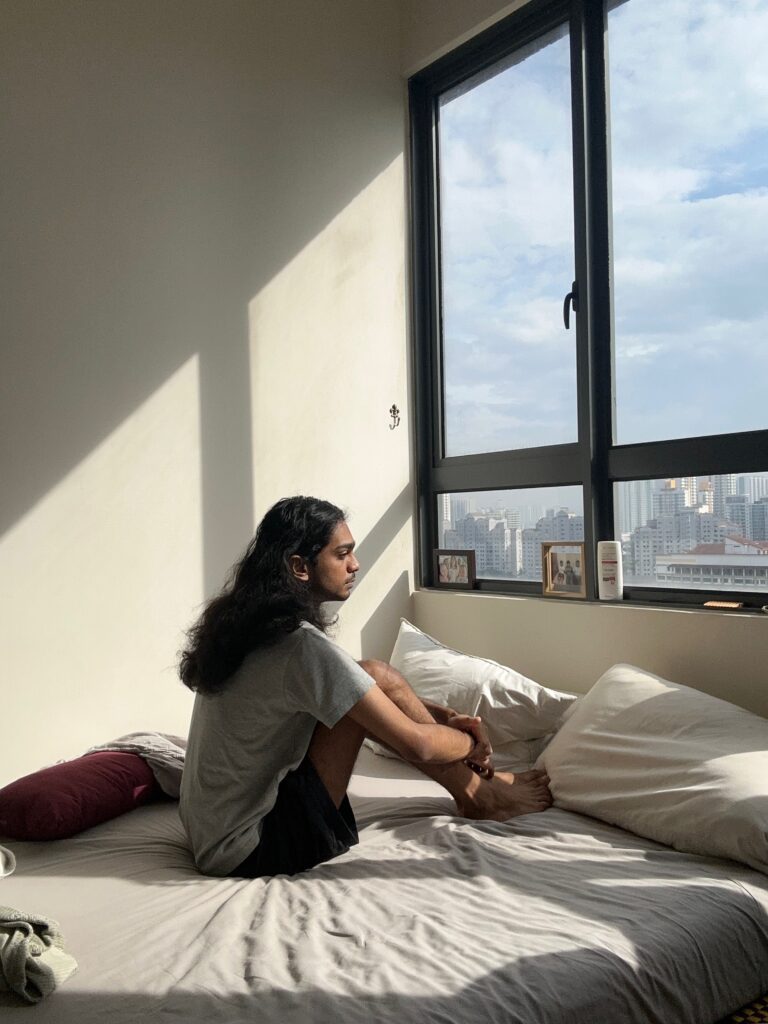

The video essayist dissected Hopper’s most renowned work – Nighthawks. The painting, as is all of Hopper’s paintings, is alive, breathing, and inviting. A portal with a great big highway-sized sign on it, a sign only privy to those akin to understanding vulnerability, nostalgia, and those, especially with a secret loneliness in their hearts – urging its viewers to leap in, headfirst. Years later, when I would grow my hair out, so very long and heavy, the weight of it inching down to my hips, I would sit before the big open windows of my bedroom and recreate Morning Sun. The video that I had watched shifted a perspective to my understanding of art, the contents of it seeping into the ebbs of my brain, sinking itself into me – allowing a new, varied point of view to grow and comprehend.

A great change took place on that day, making it a special one. I knew of such profound changes happening in books and movies and music, just never in my own life. It was a visceral feeling. It would come to my understanding, a few years down the line, that such monumental changes would always be a recurring theme in my life. This would be like something of a prophecy – change being the constant; things you come across now only making sense later, and art acting as a pillar that I would continually lean my back on. A makeshift bed I can find myself at home with. Superstition aside, for most, this is just what growing up is about.

*

Almost three months ago, my life would once again fracture. Another great, monumental change. I would once again experience some degree of a metamorphosis, and eventually, once more, come of age. I, like you, will always be coming of age. This is something that will never end, never escape us. Here is how it began: At 7:30 AM on a Friday morning, sometime in late June, an email would find its way into my inbox. It would read, “Dear Pravin, STATION is delighted to announce that we will be participating in Frieze Seoul in September 2024 with a presentation of works by Nadia Hernández, Nell, Tomislav Nikolic, and Tom Polo”. I would end up reading the email at 10 AM, when the sunshine had finally made its way into my room, pouring itself onto my face, and forcing me back into the land of the living.

Having not heard of such a gallery before and never having heard of the artists being represented, I supposed, then and there in bed, with crust in my eyes from a night of rest, that this was meant to be. A few days of pestering my editor later, and then a few weeks of back and forth with one of STATION’s curators, the interview was set. I had asked Alia – my editor – to choose the subjects. Tomislav and Nell had stuck out to her. I knew there was something there. Trusting Alia has been a fun process. It is like jumping off a ledge and not knowing what awaits you at the bottom. All you have to know is, you’ll eventually make it out alive and better than when you first started.

*

Like most of the interviews I had done for magazines, I was set to do this online. I had suggested going to Seoul and attending Frieze, a means to meet the artists, speak to them, immerse myself with the art in person, and finally have an excuse to see Seoul. The idea of traveling to see art was especially thrilling. The idea would not see the light of day. A lack of funding meant doing it online – a happenstance that I didn’t mind at all, as I didn’t have to leave my bedroom (a space that also happened to be my office). Tomislav and I would begin a correspondence via e-mail a few weeks into August. In an effort to set up a suitable time to have a conversation with him and his art practice, I would shorten his name – a means to make things more casual. Tomislav would then correct me, explaining that he would rather me address him by his full first name. “No offense taken at all. I am used to correcting people, especially in Australia”, he would explain in the thread after I had profusely apologized. I did not mean to upset the subject prior to the interview. The guilt loomed over me for some time like a bad cough. In talking to him a week or so later, our conversation would start with Tomislav seated in his studio.

Light is streaming into the room from what I can assume is a skylight. Having just woken up prior to speaking to him, my eyes still adjusting to the brightness of the day and the computer screen, it seemed to me that Tomislav had a halo forming around his head. “I’ve read your questions and they’re very thorough. I hope I’m able to answer them as honestly and succinctly as possible. I tend to get a bit nervous when I’m being interviewed”, Nikolic explains, cutting the threshold between us both with a sharp, searing knife. I let out a sigh of relief. I assured him that the both of us were going to be fine, concluding that the artist and I would be emerging out of the darkness together, hand in hand. “I don’t really like talking about my work. I’d much prefer the work speak for itself. But context helps when you’re meeting new people, and bridging that gap allows for new friendships to blossom”, he answers when asked to talk about himself and his work. I smiled to myself as he answered me. So many artists now insist upon meaning, insisting on explanation, and robbing the viewer of individual understanding.

Then, out of what felt like sheer irony to him, The artist began speaking about himself, doing so with a smile the entire time. “My background is Croatian. My parents were born in Croatia, and they had emigrated to Australia with my sister, who was three years old at the time. I was born not very long after that”. As he navigates the past, he meets himself in the present – a concurrent theme in his life and his work. Language and identity act as an important thematic tool for Nikolic’s work, work that is intrinsically tied to his past, his present, and his possible future. When he uttered his first words in English, the artist was five years old. “When I think about it, it is sort of unusual for me that English isn’t my first language. But I remember, and the remembering jolts me back into my body. English is not my first language, and it’s not like my Croatian is any better either”. There is a complex layering in the artist’s identity – being Croatian, having an Australian identity, and one of the self with his queer identity. These personal elements find themselves in his work, where layers and layers of colors fall into even lines, creating an almost kaleidoscopic, breathing entity, imploring the viewer to jump into it headfirst. Each painting is decorated with a title; some are long, and some are precise. All tell a story. It is dependent on the viewer to decipher it.

“I don’t know if I answered the question.” Nikolic chuckles and covers his mouth. We speak on the dissonance in one’s identity, drawing allusions from my own life to further iterate the point. He understands. “I still get it now, this feeling of not being in place. I grew up in a small but close-knit Croatian community. The first-generation Croatians that had settled down in Australia still carried certain practices and traits, traits that I saw when I went to Croatia in 1994”. The visit was jarring, stemming from the fact that the war in Croatia had just ended while one was still occurring in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Upon arriving in Croatia, Nikolic understood the displaced feeling he’d felt while growing up in the Croatian community back home. “There’s a lack of subtleties in the Croatian community in Australia, the same one that I had noticed when I visited Europe then. It’s affirming to see the deviation from the typicality of the Anglo-Saxon ways of communicating and thinking”, the artist explains. But in his rumination on the subject, he concludes that he belongs to neither here [Australia] nor there [Croatia]. “I’m straddling the borders of these two countries and cultural and societal ways of doing things.”

In his youth, the artist explains that he was unaware of the adaptation of the Australian Indigenous culture into the general consciousness of the Australian nation. He shares that the practice was something he understood and praised – a part of the Australian identity despite the issues the Indigenous people continue to face. In contrast, his Croatian identity is one that is passed down from his parents, something not practiced as a commonplace where he grew up. “Immediate. Communal”, he says. We pivot and start to talk about his art. I asked him, “You’re a first-generation Croatian in Australia, and you pursued a career in the arts. Immigrant families typically frown upon such ‘unstable’ career choices. What was that like?”.

He affirms my question, explaining that it was certainly frowned upon by his parents. He adds that his intent to becoming an artist was not one of consideration. His youth was spent appeasing his parents, feverously studying while making, enjoying, and reading about art in his own private time.

“I knew I really liked art. The interest I had in the subject affirmed my decision in wanting to pursue an education in art at university. I had dreams of working as an art curator or an art historian”, he shares. But Nikolic’s dreams would fracture in some way, leaving him to fend for himself. It was around the time of his tertiary education that the artist decided to pursue a degree in fine arts history.

To his dismay, however, he would not be able to meet the requirements – explaining that there were no art educators at the Catholic high school that he was in. “It would have been through correspondence,” he says. “There was no teacher. I would’ve been in a classroom alone, and I would have had to submit my work via mail”. Nikolic was then left with two options: to move to another Catholic school or to move out of his family home to support himself. He chose the latter. “My time at the Catholic high school was a hard one. I was facing a lot of bullying and was having a hard time with myself as I was coming into my queerness. When I brought up the idea of transferring to an arts high school, my parents were unenthused and unsupportive. So, I moved out”.

It wasn’t until years later that Nikolic began painting and developed the possibility of becoming an artist himself. It started at a live drawing class that he had taken with his friends. That is when the idea bloomed into a reality. “We had a similar-ish background, and we all loved making art. My friends and I then started exhibiting our work, and someone who I was unfamiliar with had come up to me at one of the exhibits and was interested in purchasing one of my pieces. That’s when it dawned on me that I could be doing this as a career”. He reminisces about his early twenties, detailing it to be a juxtaposing experience of equal parts joy, pain, and struggle. Upon his departure from his family home, Nikolic took on jobs to support his love for his artmaking. “Many such cases for a lot of us in the arts who are not born to rich parents,” I say to him.

He agrees. The emotional and physical labor that the artist took on to support himself in his early 20s and 30s would eventually take a toll on him. He explains, “I had a number of different full-time jobs that I’ve had throughout the course of my life. It’s really fresh for me still, but I stopped working for people in the last eight years and have taken all of that time and effort and poured it into my art”. There was a period when he waited tables, worked as a waiter, then as a pastry chef, had a stint at an event production company, and then became an executive at a designer furniture retailer. All the while, he maintained his stance as an artist, pouring whatever time he had into his creative work.

“When I was working at restaurants and bars, I found it to be chipping away at my social life. The hours were brutal, and you didn’t have time to socialize outside of work. When I was working at the event production company – a part-time role that I had secured – I found myself having more time to create my art”. It is true, it seems, that many such cases are for many creative people. After concluding his time at the events production company, Nikolic found a role as a gallery manager, one that he explains to have been fruitful and beneficial. Meeting seasoned artists and creators gave him insight into the varying differences in their art practice. “After nine years – all the while I was working on my work in my studio – I found it slightly difficult to speak about my work. The focus was put on other creators, and I took on the role of gallery manager. As such, I placed my work in the background. The experience was very fruitful, but buyers, artists, and other art people only knew me as a gallery manager. So, I did what I thought was best for my career, and I left”.

Right after, Nikolic took on a full-time role at the designer furniture retailer. “How did you manage full-time jobs while keeping your art alive? It’s a vicious cycle”, I queried. He nodded and agreed, explaining that it was indeed a lot of work that needed to be done. “I had the desire to realize my work. I was flowing with ideas, and that furthered my intent into actualizing my ideas into reality. It was all hard work though”, he adds.

Ultimately, the artist made the sacrifices he thought to be right to birth his ideas into the world. And with the sacrifices that were made, there were repercussions. His friendships, health, job opportunities, and social life bore the brunt of it. “It wasn’t a good time for me then. I was devoted to my studio sessions, and that took around forty hours a week on top of my full-time jobs. I would leave work and head straight to the studio and stay there the whole night – returning home to have dinner in between. I felt like I was in a deadlock and was not able to say no to things because opportunities were coming my way. I’m in a position now – a privileged one, of course – to be able to devote my time to my art and only my art. And I’m in a good place to be able to say no to things if I am not able to commit to it”.

*

Since speaking to Tomislav almost three months ago, and sitting on this article for just as long, the artist has since sent his book to me from Melbourne. The chartreuse-colored book now sits by the foot of my bed, neatly arranged under a copy of Petra Colin’s Coming of Age.

Since speaking to him also, I have returned from my holidays in Japan and my yearly pilgrimage to Penang. I think the hesitation in completing something – especially for me – is very much rooted in the fact that I don’t really want that thing to come to an end. Speaking to Nikolic was a gift, something that was given to me, as though the stars were aligned just right; a means for me to understand something deeper. I peer through the archives, the conversation of him and me from ages ago when my hair looked exactly how I wanted it to, and the artist looked like an angel. I fast-forwarded to the part where he talks about his artistry, where I explain my allusions to his works looking like a Rothko painting.

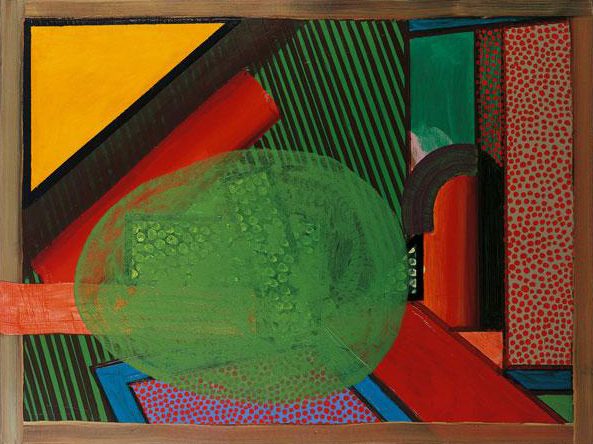

He affirms my beliefs. Nikolic’s work is of his own, but his contemporaries like Jacqueline Humphries and Howard Hodgkin– whose works carry different emotions through different use of brush strokes and techniques – are present. It is not only traditional painters who inspire the artist. He mentions Barbara Hepworth’s sculptures, which greatly motivate his work. “It is important to look at these artists’ works – be it historical, modern or contemporary – in galleries or museums as it is very inspiring. When I conceive my work, the whole body is resolved before I fabricate it”. Every detail is thought through. The size of the frame, the colors used in a painting, if a glass panel is to be added… everything amounts to the final piece, and it all carries meaning. What does the spectator see, and ultimately, how do they desire it?

I go to his Instagram page, and in the process of doing that, I roll around in my bed and knock over a glass of Yakult-matcha concoction onto the floor. Green blotches are scattered and splashed across my canvas-colored sheets. I smile. I look at my phone and don’t have to scroll too far to find Nikolic’s painting called “looking from a window above it’s like a story of love”.

It is like a scene out of Luca Guadagnino’s Suspiria. A glowing, red, beating heart thumping in 2D. Cascading around it are colors to contrast the red box; the beating heart. I remember what he said to me about his process. Coating each piece with layers and layers of paint to create the illusion of depth, each layer of paint containing marble dust. Heavy is the painting that sits in its frame for the world to spectate at. I look at it with my rose-colored glasses. I yearn to touch it and observe this painting in its golden enclosure. “The frames are part of the art piece, too. I work with fabricators to come up with specific frames for the pieces that require it. Some of the pieces take months to complete. The drying of the paint is tedious, so whilst working on one piece, I am working on others in tandem”.

DUP DUP. I think of the heat of the Dubai desert. Sandy is my desire for this painting. I wish to place my lips on it, to kiss its sandy texture. It is thumping its beating heart for me. The artist had released the images two weeks online after we had spoken, and I had looked at it again and again, all the while I was in Japan, my ear firmly planted on the chest of another, listening to their beating heart.

*

When I first started watching Nerdwriter1’s videos, I was thrilled to see how much love he had for the artists he spoke about. While away, I revisited his Edward Hopper videos for research and, in turn, found one on Gorgio de Chirico – an artist obsessed with surrealism and the metaphysical. As I was strolling around the town of Kobe, I found myself at the city museum, and lo and behold, there he was – de Chirico. The pieces were beautiful and open, wild and nonsensical, like a dream. I look from the left of the past to the center of the present.

I think of Tomislav Nikolic, probably in his studio on a Wednesday night, probably at home, curled up on the couch watching television. I spoke to him recently via text. He was shocked at the current political state of the world, and to that, I relate. I’m at odds with the circumstances of so many things at the moment. I observe the vastness of his paintings from so very far away, in my bed in Kuala Lumpur.

I take a deep breath and think of Hopper and de Chirico and Rothko, and of the vastness these paintings provide, and how similar they are to one another and all the while not similar at all. And of the feeling each piece creates within me – a deep stirring, a great gurgling. I burp out marble dust and wake up from my dream. I smile and think of Tomislav Nikolic. Kismet. Fated. An artist I revere. A mentor I wish to work with someday, a great figure to learn so much from.

His paintings are created for the desire of the viewer: sexual, breathing, layered in meaning, and ultimately reserved for the singular viewer. Like a body primed and ready for the picking. But it is singular in meaning for it is dependent on the individual. So, each piece changes but always remains the same. It is always, however, breathing.

I exhale once more. I taste the grittiness of marble in my mouth and hear a thumping coming from my locked phone screen. I look forward to seeing what more he has coming. I tuck our interview away onto a blue hard drive I call bump drive. A ghost floats in the background. Nell is calling.