With borders shut and resources stretched thin, the COVID-19 pandemic has led Malaysians to search for a scapegoat amidst a period of uncertainty, which in turn has targeted the most vulnerable communities in this nation. The increase in xenophobia and hate speech coupled with refugee boat turn-backs and immigration raids led to the #migranjugamanusia online campaign in May protesting against the harsh treatment of migrant workers and refugees. It sought to create a united voice in humanising their stories while educating people to see them as human beings who are just like us.

The Transcultural Lullabies Project pairs five narrated Rohingya and Malay folksongs and lullabies, unified with a patterned artwork by Sharon Chin as “one small bridge for the immeasurable distance and pain between our peoples.” We hear from Rohingya poet Mayyu Ali and Malaysian artist Sharon Chin in a conversation about their audio-visual project regarding their thought process and experiences in highlighting the two cultures – for in the end, music plays a universal role in our respective communities that have hopes and dreams, and we have a lot more in common than we think we do.

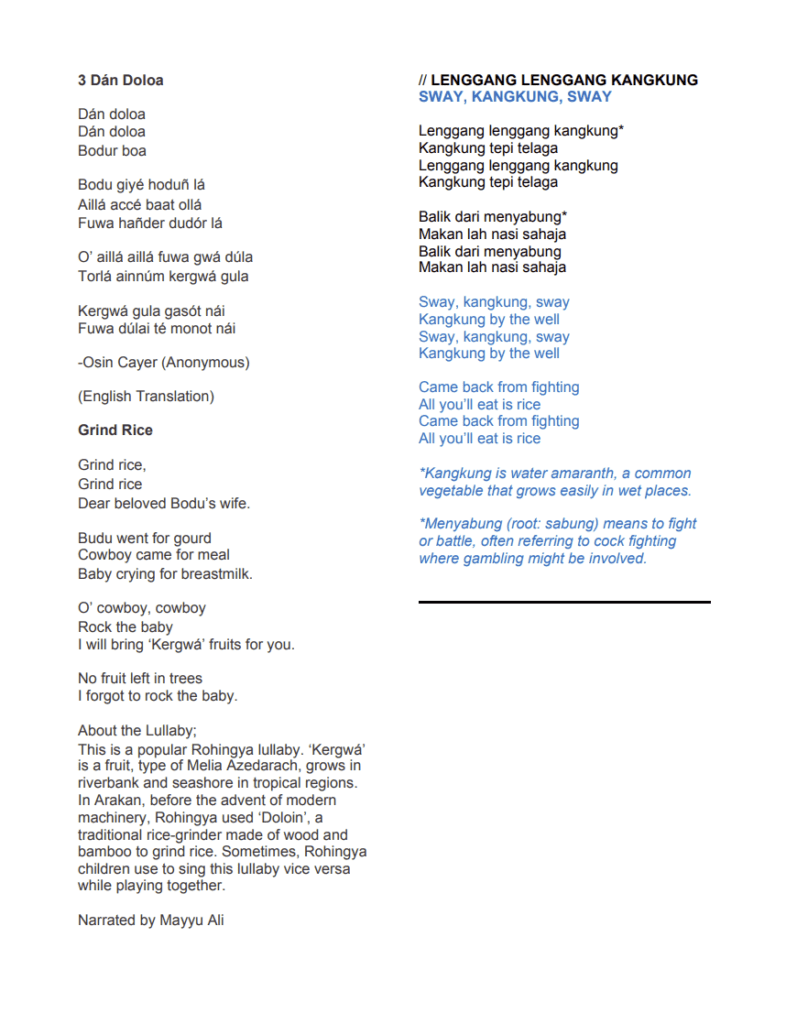

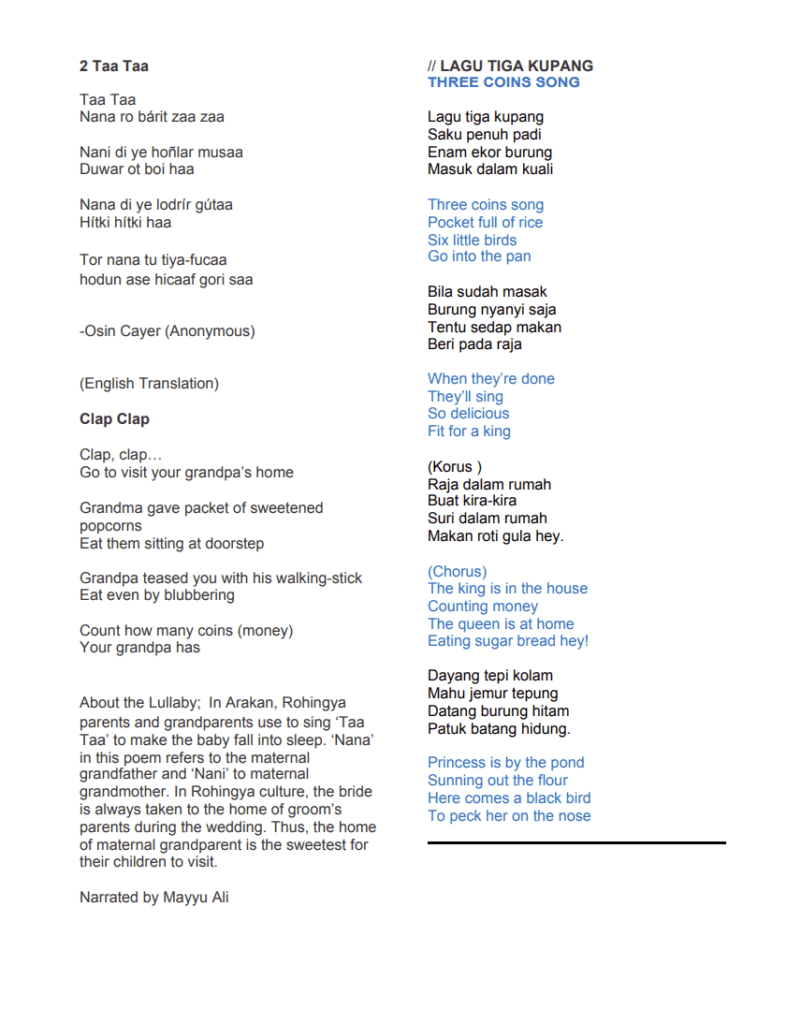

Rohingyar Sálon (Rohingya Dishes) & Ikan Kekek (Sea Fish)

Taa Taa (Clap Clap) & Lagu Tiga Kupang (Three Coins Song)

Dán Doloa (Grind Rice) & Lenggang Lenggang Kangkung (Sway, Kangkung, Sway)

Dokin or Aalu (Potatoes in the South) & Tu Bulan Tu Bintang (The Moon, The Stars)

Jiva (Jivan) (Life) & Nenek Si Bongkok Tiga (Old Granny Three Humps)

HELLO! COULD YOU TELL US A BIT ABOUT YOURSELVES?

Mayyu: My name is Mayyu Ali and I am a Rohingya born in Myanmar. During the violence in 2017, the Myanmar military burnt my home and village. My parents and I escaped to Bangladesh, where I am now a refugee in Cox’s Bazar. In 2019, I published my debut book ‘EXODUS’ and established ‘Art Garden Rohingya’, the online website that revives Rohingya literature, arts and culture.

Sharon: My pedigree says visual artist, but I’m really a mongrel who does all kinds of things – contemporary art, writing, production design, illustration. I was born in PJ and grew up in malls around the Klang Valley. Ten years ago I moved to Port Dickson. I live here with my partner, two rescue cats, and an overgrown garden.

HOW DID YOU COME TO COLLABORATE WITH THIS PROJECT?

Mayyu: Sharon and Nabila (from Arts Equator) reached me through an email saying that they were looking for Rohingya artists and found my artwork online. I was excited and said yes on the spot wanting to build bridges between two different cultures. We selected five folksongs that have similar perspectives. Sharon illustrated some patterns on those folksongs that are incredible. Working with her is solidarity. I enjoyed working on this beautiful project.

Sharon: Arts Equator asked me to do something COVID-19-related for their website. I knew of Mayyu’s work through his website and The Art Garden Rohingya, a platform for Rohingya art and poetry that he co-founded. Arts Equator facilitated our collaboration. We started with a three-way voice call, then email and text messages.

THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC HAS EXACERBATED MALAYSIA’S UNJUST TREATMENT AND DISCRIMINATION TOWARDS REFUGEES AND MIGRANT WORKERS, CULMINATING IN THE #MIGRANJUGAMANUSIA ONLINE CAMPAIGN IN RESPONSE. WHAT WERE YOUR AIMS WITH THIS PROJECT?

Mayyu: It’s a nightmare the way Malaysians are treating refugees, including my fellow Rohingya. My aim with this project is to bring the attention of the Malaysian people to my fellow Rohingya refugees in their country. I want them to see refugees as human. I want them to embrace the light of humanity. We’re not just refugees. We are people. We have our own culture and traditions. We want the world to stand by our side till we return to our homeland in Myanmar and enjoy our rights as all other ethnic groups of people in Myanmar.

Sharon: Yeah, Covid-19 has us stuck at home, hooked to our screens. The distorting effect of media is just exponential. Maybe the dehumanisation of the Rohingya is a projection of our own failure to be human in this merciless age of industrial capitalism. My aims… I don’t know. I wanted to give something. A drop of rain.

WHY ARE LULLABIES AND FOLKSONGS SO IMPORTANT IN ONE’S HERITAGE?

Mayyu: We seek refuge in the light of arts and culture and find resilience even after the disappearance of the written form of our language in the face of wars during the ancient times, the aggression wars during the British colonial era, and now in the hands of the dictatorship in Myanmar. There are Rohingya lullabies and folksongs that have been passed from one generation to another through oral tradition.

When I was young, my friends and I used to sing folksongs while playing, which is one of the sweetest memories for a Rohingya in Arakan. Before going to bed, our grandparents and parents used to tell us traditional folktales and lullabies. These stories created a warm atmosphere to our bonding and togetherness since the very beginning of our lives in Arakan.

Sharon: They are part of an oral tradition passed down for generations. There’s information in there about where we came from, and where we might go – if we’re willing to listen. For example, how do we reconcile the lyric ‘Budi yang baik rasa dijunjung’ (in the song Ikan Kekek) with our actions towards migrants? Can we sing those words with a straight face and clean heart? If we claim these songs are still part of us, then they hold us to a higher standard. Otherwise, we should abandon them.

HOW DID YOU GO ABOUT DOCUMENTING THE LULLABIES AND FOLKSONGS OF YOUR PEOPLE? WERE THERE ANY CHALLENGES?

Mayyu: The longer we suffer in the hands of the Myanmar government, the more we lose touch with our culture and tradition. Over the last five years, I have been documenting Rohingya folksongs, folktales, proverbs, old poetry, prose, and other artworks. The elderly group in the Rohingya community is the main resource of those ancient lullabies and folksongs, and I go from door to door in Cox’s Bazar’s refugee camps to record and document what they sing. However, the pain of decades-long suffering has agonised their minds and their memories are being forgotten. Exile not only fades away the light of Rohingya culture and tradition, it also forces us to adapt to the mixed culture and tongue of the host community.

I have compiled 50 Rohingya folksongs that have been passed down since ancient Arakan, which will hopefully be published internationally early next year. It is presented in three languages: Rohingyalish, English and Burmese. Its documentation and preservation are the best gift of legacy that I could ever pass on to the future generations of the Rohingya community.

WHY DID YOU CHOOSE THESE SPECIFIC LULLABIES AND FOLKSONGS? WHAT WERE YOUR REASONS BEHIND THE SPECIFIC PAIRINGS?

Mayyu: There are many Rohingya lullabies and folksongs, and we chose those specific five songs to pair with Malay ones that have a similar sense of contexts in order to give the importance of trans-culture to people.

Sharon: At first, the plan was to illustrate Rohingya songs only. When we first talked, Mayyu asked a question: Will it only be Rohingya songs? It made me pause. That was the turning point that led to the idea of pairing Malaysian and Rohingya songs, so they could ‘stand side-by-side’ in companionship and solidarity.

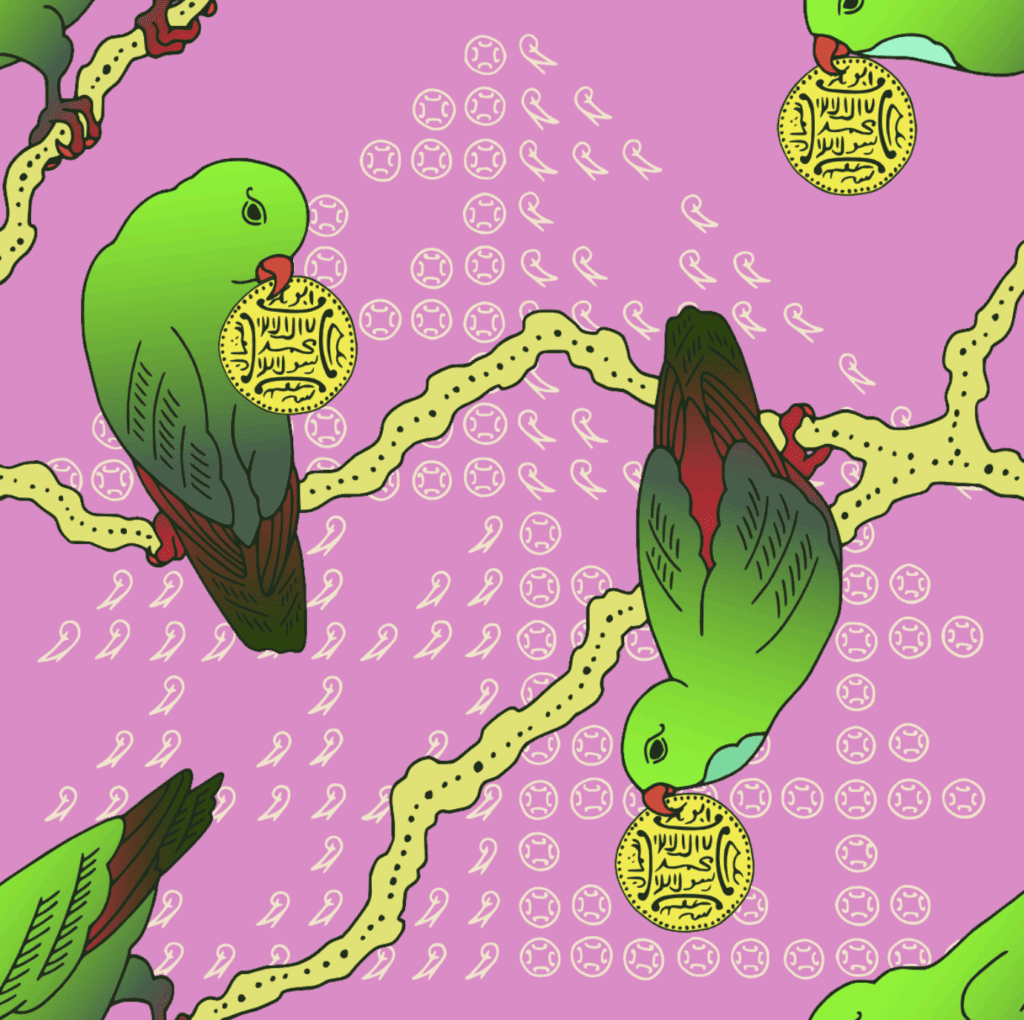

I did the pairings, just following my instinct. Some were because of similar images – Rohingyar Sálon (Rohingya Dishes) & Ikan Kekek (Sea Fish) both reference two kinds of fish. Others were paired for contrast, like Jivan (Life) and Nenek Si Bongkok Tiga (Old Granny Three Humps).

WAS IT CHALLENGING COMING UP WITH THE ARTWORK TO BRIDGE THE TWO CULTURES? WHY DID YOU SPECIFICALLY CHOOSE TO USE PATTERNS?

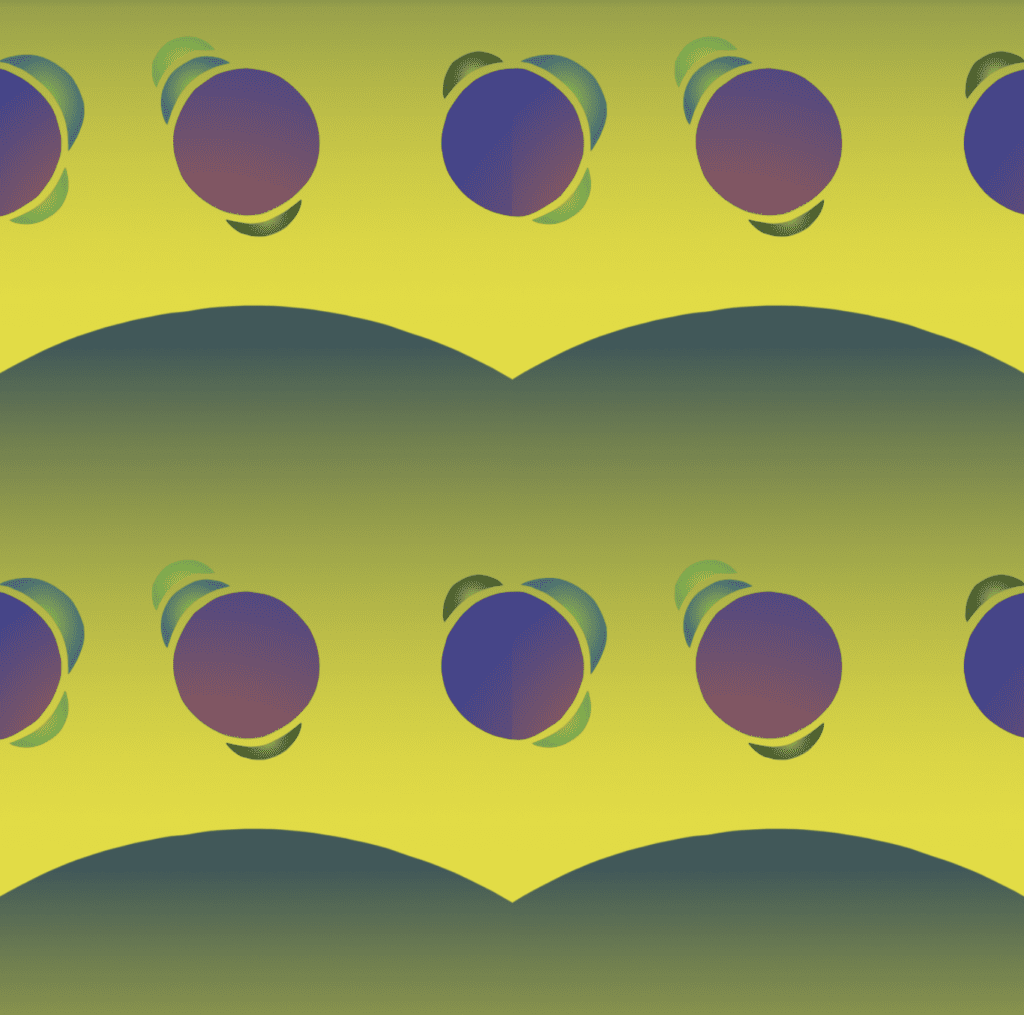

Sharon: Yes, it was a challenge. It’s about expanding the notion of one’s self, one’s culture, to embrace another, but still respecting and distinguishing the other. That’s a work of the imagination, to show how cultures coming together creates a new space that is incredibly rich. No one has to give up anything. It’s a paradigm of mutual increase and prosperity.

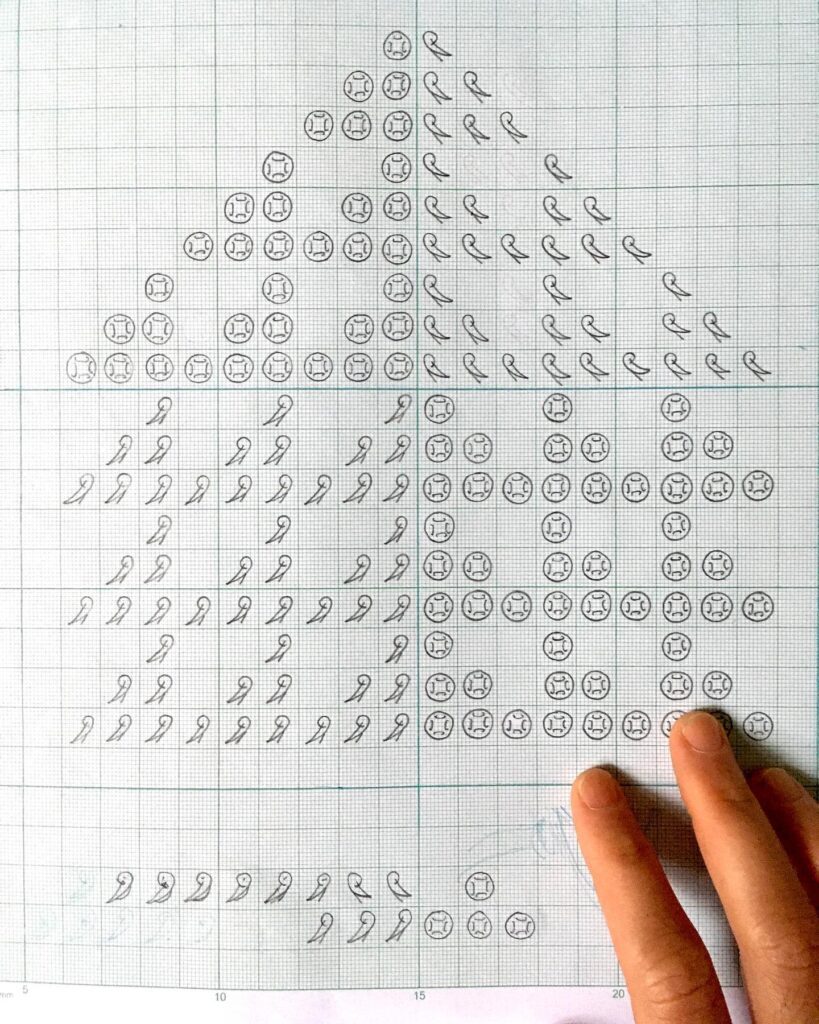

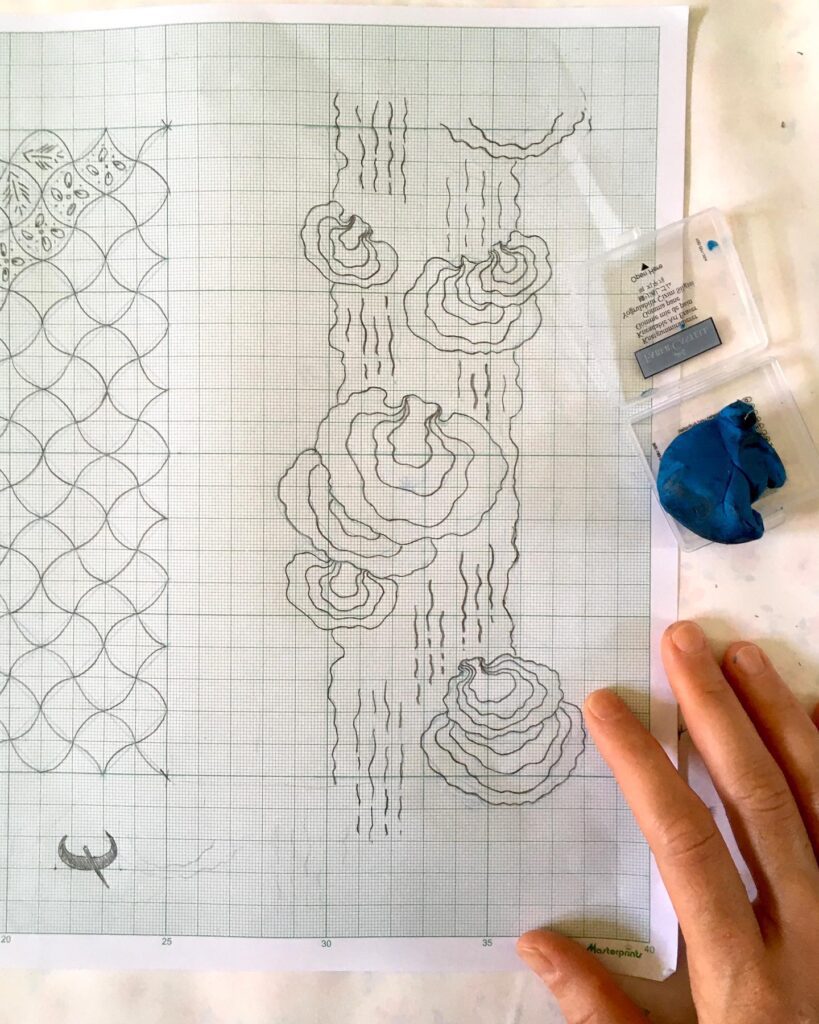

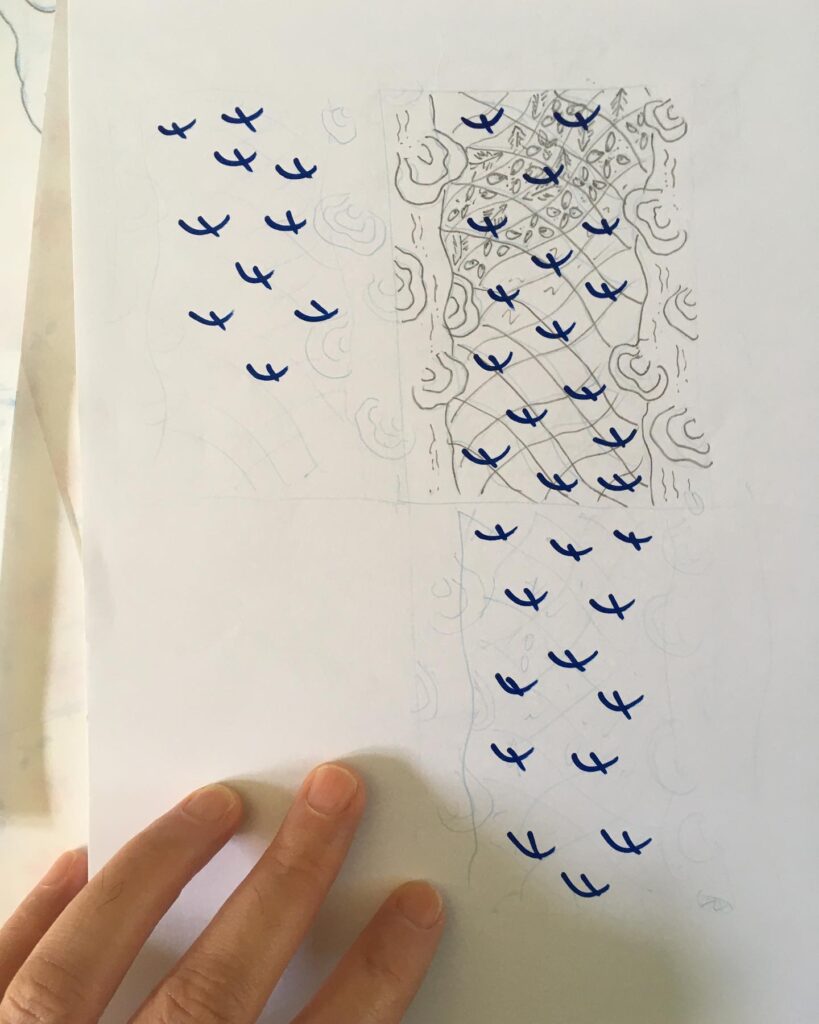

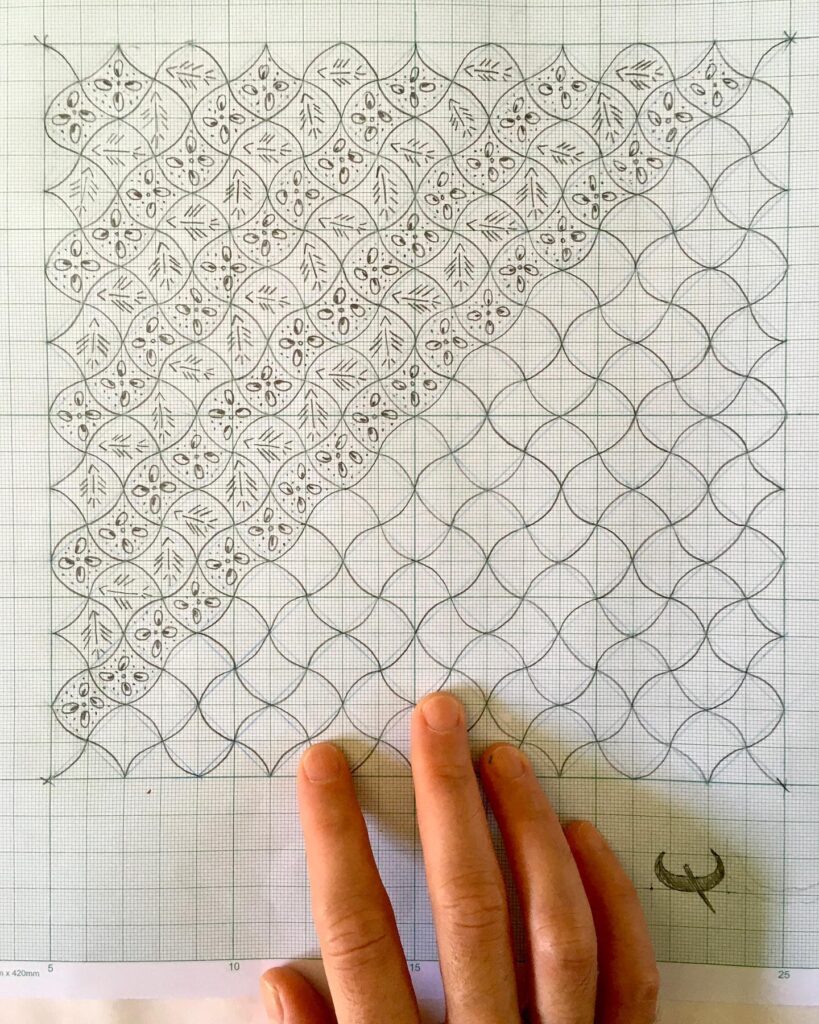

I chose patterns because they are like the visual equivalent to folksongs in our region. Even if we didn’t study art, we all know how to ‘read’ the ‘meaning’ in patterns because they’re part of our traditions through batik, weaving, and carving.

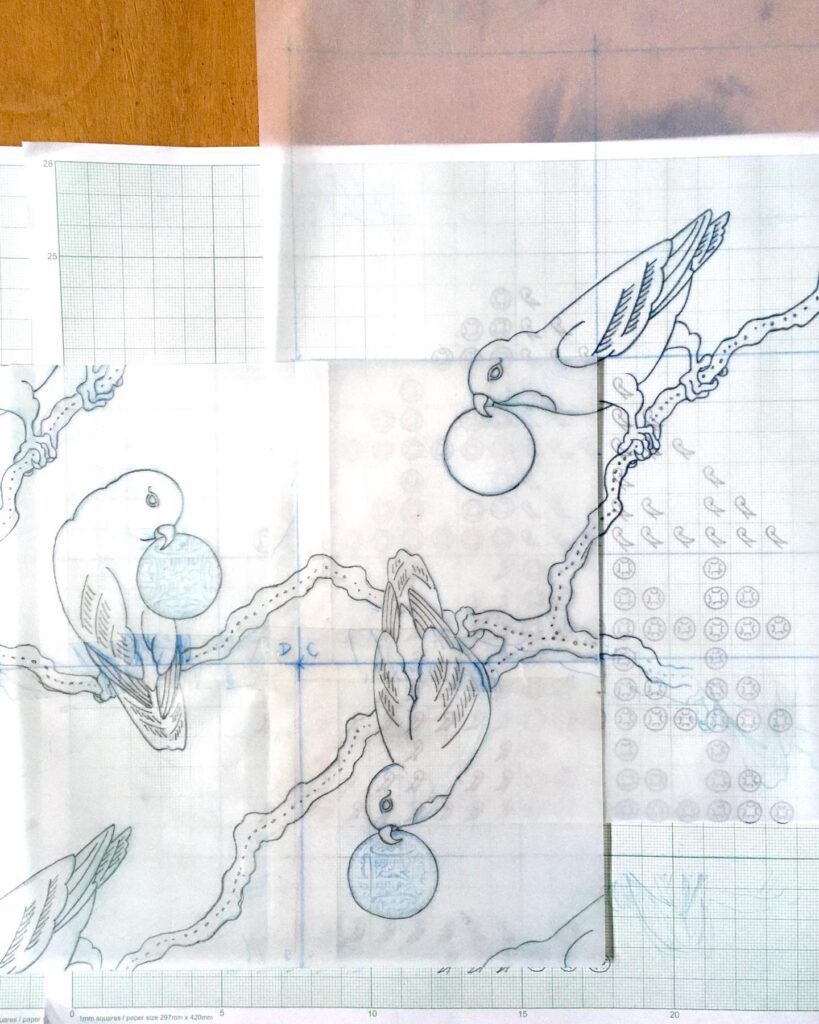

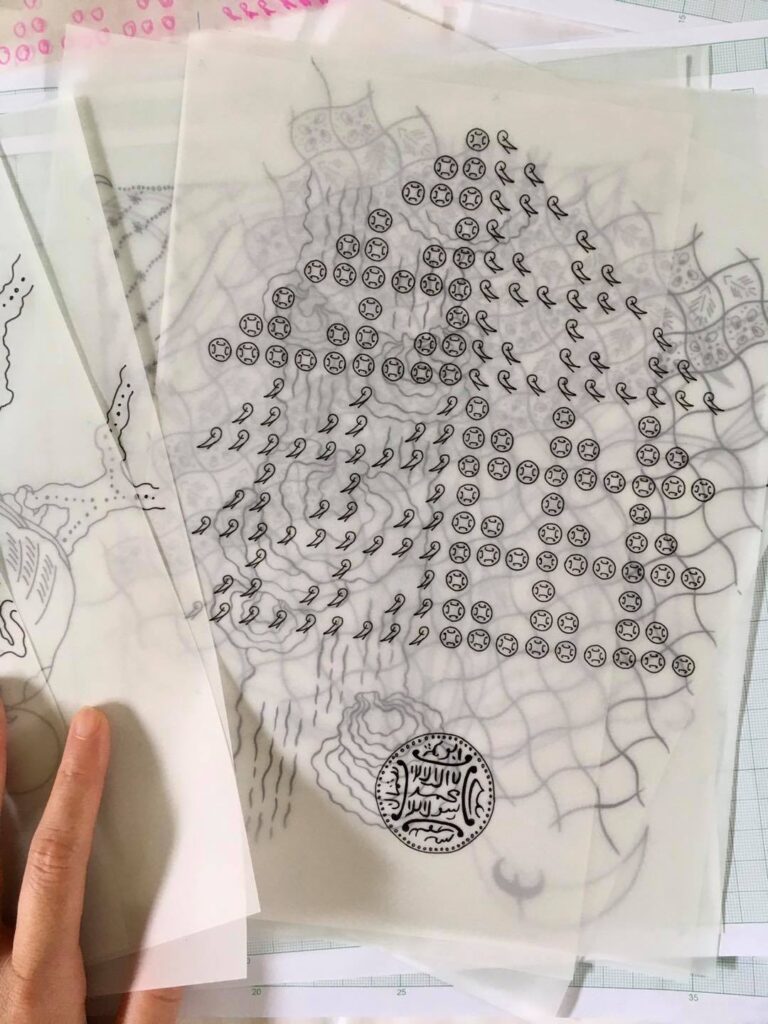

WIP

FINALLY, WHAT DOES THIS PROJECT MEAN TO YOU AND WHAT DO YOU WANT PEOPLE TO TAKE AWAY FROM IT?

Mayyu: As I said before, for me this project means ‘building bridges’. We are not just refugees – we have our own culture and traditions. I want Malaysians and the world to see as human. All we want is to return to our homeland in Myanmar to save lives and to enjoy our rights – but now we need your solemn ‘human solidarity’, not mistreatment and ignorance.

Sharon: Firstly, this project means trust. Artists often come with good intentions, but we can end up further ghettoising or instrumentalizing others to make ourselves look noble. I’m grateful to Mayyu for his trust in me and this project.

Secondly, I want Malaysians to look at the truth of who we are. For example, if we know how we responded to Vietnamese boat people in 1978, we will understand that the roots of our xenophobia go back into history. It’s not just a matter of the issue of the day, but one of identity. How we treat others reflects who we are, and how we relate to each other, and to the land. All the old myths are clear about the fate that awaits those who turn away strangers in need. We live in a land of plenty and we must strive to be worthy of it.