Filmographers far and wide have understood the efficacy of a cinematic medium, in exaggeration or hyperreality to convey narratives that critique the social, economic, and political implications of a nation.

Anthropologist Terence S. Turner wrote, “Man is born naked but is everywhere in clothes (or their symbolic equivalents).” Bodily adornment, however frivolous a business it may appear to some, is for the culture, as Durkheim said of religion, la vie sériuse (a serious matter). Evident in subcultures like the goths and the punks, the dress is one of the most specialised in shaping and communicating personal and social identity.

Through these two statements, the point is clear: the homogeneity between film and costume to tell a story is an obvious one. Just as obvious, is Malaysia’s favorable film genre: Melodrama. A genre that through its fantastical imagery and expressive characters gives us a means of seeing and understanding the world of its time. Jins Shamsuddin’s Tiada Esok Bagimu is no stranger to that. Released during Malaysia’s peak liminality into modernity in the early 1980s, the film tackles the goals of westernisation while trying to keep in line with the Malay and Islamic National Identity. Like each shot in the movie, each dress is semiotic of the times presented.

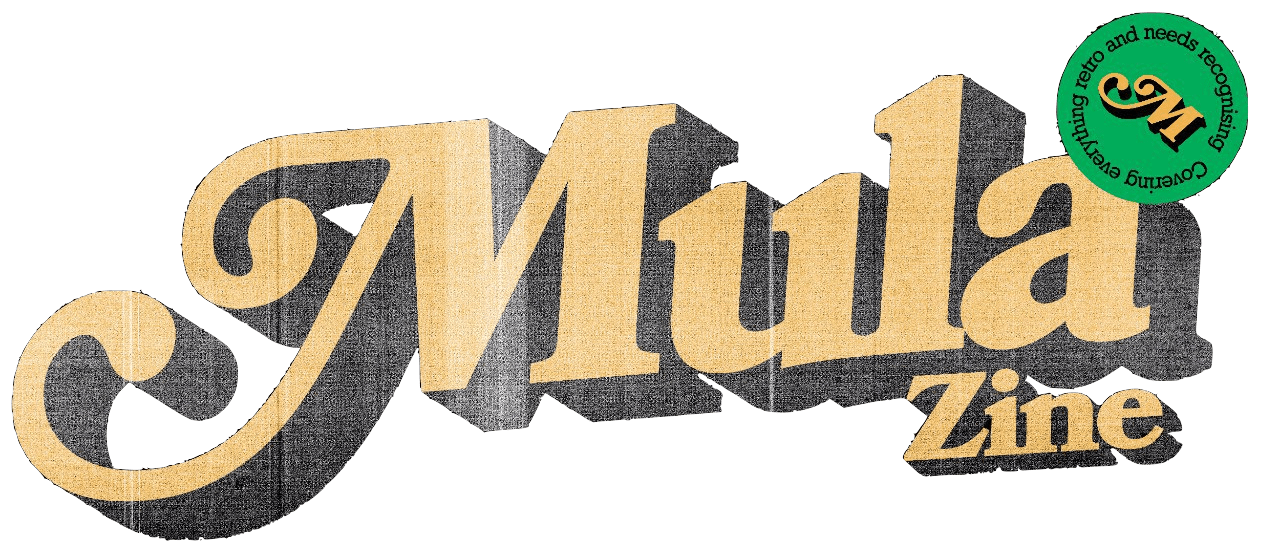

In true 80s fashion, the film is painted in pastel hues of soft pink, blue, and orange tones to convey a collective cultural expression. Tiada Esok Bagimu projected a new image of glamour and beauty for Malaysia’s capital, Kuala Lumpur while critiquing the very structures of westernisation. The 1980s was a time for Malaysia’s growth on a global scale and the feminist ambition for an independent woman should be noted. However, the film Tiada Esok Bagimu stays true to its melodramatic roots where men and women are stereotyped into colour categories to convey their specific roles. The film’s main character Noraimy along with her female counterparts is often dressed in pink from the very first 5 minutes and later throughout. The men of the film namely her father and brother Amir are often dressed in blue perhaps to point out the blatant fact that they are men. Colour theory is common in semantics: pink is soft, gentle, and feminine while blue is stable and secure.

Using colour theory to dissect the meaning of each clothing, we also see the colours of Islam show themselves through pinnacle moments of the film: when Noraimy wears a green dress in her first scenes to proclaim herself as a gift from God brought to bring her father happiness and a second chance after the killing of his first daughter, also ‘Noraimy’. We see Amir wearing yellow for the first time when he goes to comfort his sister who has run away from home after a series of terrible events (finding out she’s adopted, being raped, and the subsequent break up with her fiance), through a western lens it could be alike to greeting a sick friend with yellow flowers. Noraimy wearing red getting out of her red car when she learns that she is an adopted child– red signifies courage and bravery.

As the film progresses, its attempt to reveal the weaknesses of the Malaysian upper class (a family of lawyers, architects, and a minister) is evident. At the beginning of the film, we see Ghazlan sporting a shirt and trousers when the secretaries at his office make a comment about him always staying late at work. He later arrives home for his daughter Noraimy’s birthday and accidentally reverses his car on to her––a critique of his mixed priorities, westernised lifestyle, and neglect of tradition that has resulted in an unfortunate event.

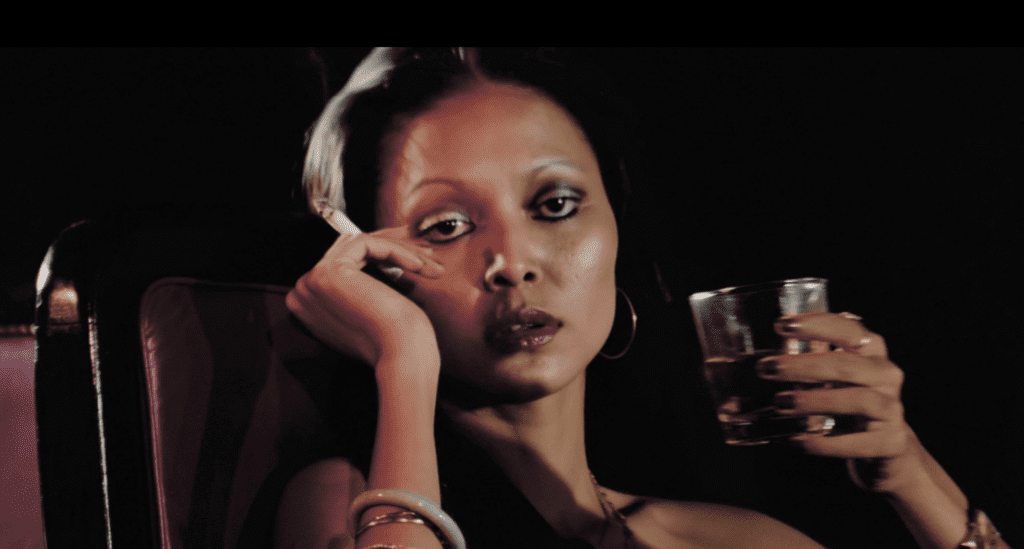

Later, throughout the movie, after he goes blind as a punishment from God for his mistake, he goes back to a more traditional dress. He even lectures his son (who’s wearing flared trousers and a tucked-in flowy shirt) on the importance of sticking to a national architectural design etiquette instead of adopting a modern one near the end of the film. His glamorously dressed daughter on the other hand, who sports 80s trends of almost there eyebrows, striking shimmery eyeshadow, and bold pink lips, gets raped many times throughout her life but more central to the film, by a minister at a party whose priorities, like her father, in the beginning, are also adrift.

The last 30 minutes of the film brings Noraimy to a Kampong in Taiping, a less-developed site in Malaysia. The end scene shows Noiramy in an Islamic dress making a revelation about her life and shows her willingness to give up her life as a daughter from a rich family for a traditional life in a poorer one. The scene again, emphasizes the superfluous nature of wealth and modernization without faith and tradition.