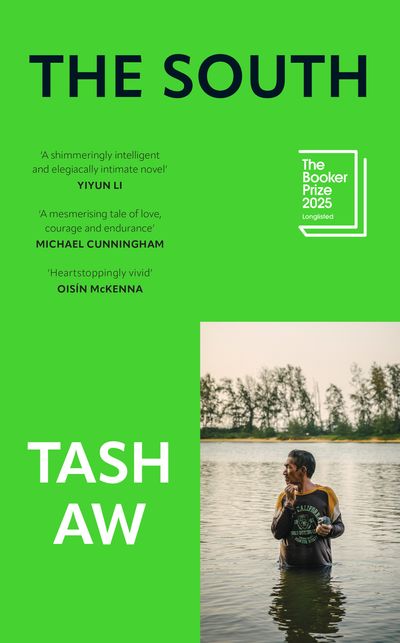

Even from inside the cafe, our conversation is interrupted by al fresco-dining valley girls lamenting, with a kind of American sadness, their summer pilgrimage slipping away (at least, they’ll always have Paris!). Aw admits his preferred cafe is a smaller, local spot a couple doors down, but this felt more appropriate for our meeting on a Monday morning. It was a few weeks before the announcement of the shortlist for the Booker Prize and Aw was in the running for the third time. He had made the longlist twice before with his debut novel, The Harmony Silk Factory, and The Five Star Billionaire. But his latest novel, The South, has garnered even greater critical acclaim.

The book follows the Lims, a middle-class, Malaysian-Chinese family, as they return from their suburban lives in the city to a derelict, rural farm in the South. Central to the novel is Jay, a precocious teenager grappling with the demands of his father’s expectations and his budding sexuality. His parents, Jack and Sui Ching, offer little recourse. Neither do Jay’s sisters, Lina and Yin, both older and preoccupied with their own lives. At the farm, familial relations are further strained by Jack’s half-brother, Fong, who manages the land along with his son, Chuan. If each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way, the Lims are stifled by an absence of communication, a deadly silence.

On this occasion, their trip to the South is markedly different; the passing of an elder relative has brought questions of inheritance to the fore. “You have this piece of land that is really worth, in modern terms, not very much,” Aw explains. “But sentimentally, you know that it’s bound up in other people’s expectations, desires, hopes and failed ambitions.”

It is a classic literary premise. Aw cites Anton Chekov’s “Uncle Vanya” and “The Cherry Orchard” as sources of inspirations, but also the epic works of Rohinton Mistry and Vikram Seth: long-drawn sagas that capture a historical period through the vantage point of one family. The South seeks to stand in this lineage. As the first novel in a planned quartet, Aw abandoned his ambitious plans to write an 800-page epic and adopted a different structure to tell his story which will meet the Lims at different stages.

The novel is as much a coming of age bildungsroman as it is a striking portrait of a country in crisis. Aw deliberately omits the place and time in which the story is set, but any Malaysian would be quick to recognise the South to be Johor and the year 1997 when Asia was struck by a financial crash.

After buying into the vision of a new post-Cold War global regime, Malaysia embraced the alleged triumph of liberal capitalism and focused its economy toward export-driven industrialisation. The Malaysian project–what Aw describes as “getting educated, buying a car, becoming homeowners”–was in motion. But by the middle of 1997, the fantasy proved to be a farce. The Thai stock market collapsed; like wildfire, the economies of Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines caught on. “There was a real sense of fragility… that we were just victims, a small country against the tide of global economics,” Aw recounts. “Reality couldn’t keep up with our dreams.”

He captures the distinct anxieties of the crash through the Lims’ grievances: unintended victims of a failing financial system. Jack complains that “our stupid currency is worth nothing these days, the Americans are screwing us, we can’t afford a new car,” while pointing out the government’s pitiful attempts to blame external actors: the IMF, the West, George Soros (actual statements made by the former administration). “Light a match and the whole country will go up into flames,” Jay repeats across the novel. He is referring to the volatility of the economy but also quite literally to the weather. As a result of El Niño and widespread forest fires in Indonesia, a hazy fog fell upon Kuala Lumpur for most of the year.

When Malaysia subscribed to this new global order, it did so with an important caveat: free markets without personal freedoms. The two were treated in silos. After all, this was Mahathir’s Malaysia. And like many of his regional counterparts, Suharto and Lee Kuan Yew among them, he embraced the belief that individual liberty hampers economic growth. Human rights were branded neocolonial impositions of Western ideals and rendered incompatible with Asian values. For the Malaysian project to succeed, the government justified its rule with an iron fist.

While constitutional crises and political detainments became hallmarks of the Mahathir regime, politicians rested easy so long as the Petronas towers shone bright. It was a symbol of Malaysian hubris. Aw expertly weaves examples of basic rights being curtailed throughout the novel: discrimination on the basis of race, police mistreatment, censorship.

The bitter irony is that The South has had a lukewarm reception in Malaysia. Not for a lack of demand nor interest but rather, quite simply, because the book is not available on bookshelves. Much of the uproar has resembled an Orwellian kind of self-censorship: conservative keyboard warriors urging for an official ban on the novel. It was lambasted as immoral, too transgressive for an increasingly religious society. In the face of looming controversy, leading bookshops capitulated and discontinued carrying stock of the book.

I raised this with one independent bookseller who regrettably explained that the legal frameworks in place grant the home ministry absolute discretion to seize any books from their shelves. The absence of any appeal mechanism offers no due process. For a small player in the field, his slim profit margins could neither afford the controversy nor the loss of sales. It is nevertheless disheartening seeing the novel warmly celebrated across storefronts in New York and London while, in Kuala Lumpur, the book has to be discreetly pre-ordered, handed over a counter in secret exchange.

Aw scoffs at this outcry. “Whatever controversy there was, was very minor.” He has avoided addressing the backlash in previous interviews, refusing to platform his detractors. However, his frustration is visible when we speak. “It must have come from people who never actually read the book because in terms of queer novels, it is really, really soft. Almost to the point of euphemism where I questioned if I was being too timid.” This is not Edmund White narrating a passionate affair or David Wojnarowicz discussing late night cruising. Aw writes in code. The opening scene of the novel, where Jay and Chuan have sex for the first time, is ridden with metaphors. The act itself becomes obscure; it is hard to make out what is actually happening.

When Aw describes the boys, he envisions them huddled together, hearts palpitating. Or resting on each other’s chest, fingers tracing their bare skin. “I mean almost nothing happens… but you know, all love affairs when you are sixteen are all-consuming,” Aw explains. “No one just casually falls in love at that age.”

His ethos is to “create an emotional, intellectual and cultural space that other people can fill with their own version of how society can be lived or how it should be made. My work is about presenting what is right before us. If you are going to be uncomfortable about that, the problem is not mine. The problem is yours.”

He seeks solace in his fellow cohort of writers, many of whom he calls close friends. “I don’t think I would still be a writer if I didn’t have these friendships. I think it would be much more difficult. My closest writing friends are people who come from outside the traditional spheres of traditional writing,” he says. Among Aw’s inner circle includes writers Yiyun Li and Edouard Louis, human rights lawyer Alison MacDonald, and photographer Ian Teh.

Now in his 50s, Aw continues to write with daring conviction. His most recent essay tackles the aftermath of the violent racial pogroms on 13 May 1969 in Malaysia which claimed over a hundred lives. “There are numerous stories of what ethnic Chinese families did to survive on that long day and night of May 13—hiding in homes and shops belonging to sympathetic Malay neighbours, building barricades outside their houses, driving out of town in the dead of night without their headlamps on.” He was born two years after the riots, following which a new social contract in Malaysia was drawn. Unlike the founding vision of a multiracial, egalitarian country, the new agenda placed the ethnic Malays, the Bumiputera (“sons of the land”), at centre stage.

The othering of non-ethnic Malaysians established a de facto two-tier citizenship system. And yet, very rarely would Aw even hear about the May 13th tragedy or its political ramifications. “I became a writer because I wanted to put a name to these things. It was simply about providing relief by talking about them because I grew up in silence.”

When so much of the hostilities surrounding May 13th revolved around disputes over entitlement and ownership, Aw radically imagines what it would look like for a Malaysian-Chinese woman to become a landowner. Sui Ching, who legally inherits the land from her father-in-law, seems to understand this significance. “One day I will own a piece of this earth,” he tells her. “Somewhere in the world, and never have to move again, I will die there and my bones will sink into the soil and I will become part of what belongs to me.” The land was purchased following WWII; it is barren and in decay. However, for an immigrant family in Malaysia, a place to call one’s own acquires particular importance.

The day before we meet, hundreds of thousands of protestors assembled across the Channel in support of Tommy Robinson’s far-right Unite the Kingdom march. A few weeks prior, Keir Starmer welcomed Isaac Herzog to Downing Street as Israel rained bombs on Gaza. Closer to home, Anwar Ibrahim’s government continued its challenge of a recent Court of Appeal decision which strengthened free speech. How should writers respond to an increasingly hostile political landscape? Is there an onus for them to do so?

“I have a real incredible admiration for activists out in the street, actually putting their bodies on the line. But somehow I think writers are complementary to that. Our role is specifically to speak and not shy away from shame,” he says. To this end, writers have historically taken arms through literature. Most recently, the genocide in Gaza has spurred an outpour of important work: Isabella Hammad on student protests and reading amidst a genocide, Mohammed El-Kurd on the palatability of Palestinian victims, Tor Krever’s dedicated international law review on Gaza. Aw has also joined this chorus in expressing solidarity with Palestine. “We have the most influential writers and thinkers in the world battling against a scandalously inequitable system and yet, nothing seems to be changing. What you have is this growing sense of powerlessness and nothing can be done. That is the greatest thing that we have to be aware of. The fight is never over.”

In his own way, Aw fights through fiction. His stories become sites of resistance and imagination. When much of queer literature has focused on loss and grief, at the end of the novel, Aw defiantly dares to envision its antithesis, queer joy. Two boys dancing: euphoric, in the open, without shame. He makes clear Jay and Chuan’s relationship can bloom outside of Giovanni’s Room, if only for a fleeting moment. They are given a happy ending, which sadly is still revolutionary, even more so now perhaps than ever.