When I think of a new year and what it brings, it’s little forgivenesses, its secret hopes like flowers smothered in a curled fist, there is a child in me who thinks: Bliss. A clean slate. Fresh beginnings. This, of course, is an illusion. ‘So much of any year is flammable,’ the Palestinian-American poet, Naomi Shihab Nye, writes in “Burning the Old Year”. ‘Quick dance, shuffle of losses and leaves, / only the things I didn’t do / crackle after the blazing dies.’

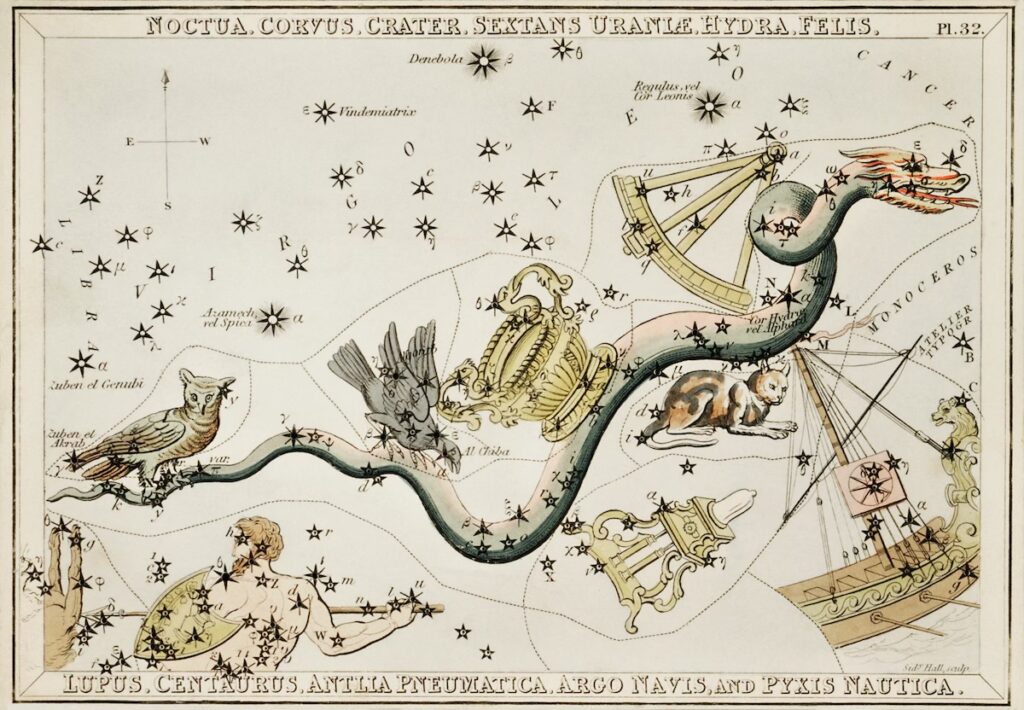

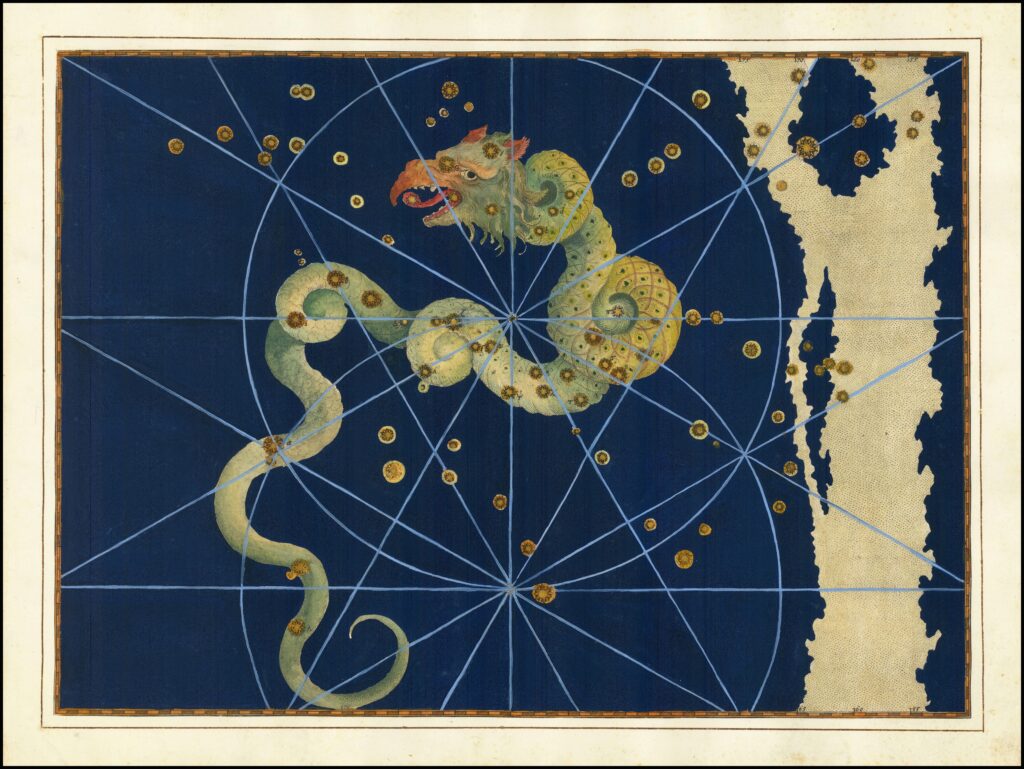

I know it is the year of the dragon because my family is full of them. I grew up with two: my father, a wood dragon born in 1964, and my sister, a metal dragon whose flame was ignited in the embers of an old century by the light of a new one. Whenever they disagreed, my mother would always say her two dragons were fighting, and that’s how it felt: the promise of fire and smoke crisping the air, a tension that could singe snow.

The Lunar New Year, if you’re following the Chinese calendar, falls on the second new moon after the winter solstice. It’s a different date every year, one that marks the end of winter and beginning of spring. As I research this essay, I learn new things. The word “lunisolar”, for one: ‘of or concerning the combined motions or effects of the sun and moon’. That “lunar new year” is a bit of a misnomer because some celebrations across the world fall on different days of the same year, depending on their adherence to the Buddhist, lunar, or lunisolar calendars. That naming this time of the year can be politically inflammatory; that even in the midst of celebrating the same event for the same reasons, we slip into our propensities to territorialise and lay claim, to bicker over definitions and etymologies. That we are creatures of conflict, which I already knew.

Dragons stir the imagination because they sit on that seductive threshold between beauty and terror. There is something silken and cunning about them. They spit fire. They dwell in deep gullies and sinister caves, on the tips of perilous mountains. Sometimes, they even emerge from the depths of the sea. Maybe one of the best things about them is that we don’t know if they really exist, which means they can be anything we want them to be. We can project onto them rage and destruction; depthless passion and burning desire; secret threats that lurk in the dark with forked tongues. In a way, from the moment they alighted upon the human psyche, dragons were a manifestation of our fears.

Every good origin story has its monster, and in Chinese lore, the spring festival’s beast is the nian. It’s not a dragon, but a lion with the body of a dog and long, sharp teeth. Legend has it that on the night of the second full moon, the nian would descend upon villages, leaving a stream of dead bodies in its wake. But people soon found out that, like all monsters and men, it was also afraid. They learned that the nian didn’t like the colour red, and would scamper away from loud noises. This monster’s fears are allegedly what spawned the enduring tradition of hanging up red paper lanterns and donning crimson clothes, of setting off firecrackers and swaying to the thrum of the lion dance. Was our initial celebration of this time of year rooted in how we conquered fear, I wonder, or how we began to rely on another’s?

As I know it, at least, the nian barely features in how we celebrate today. Even as we perform the rituals and honour the superstitions, I don’t think many of us are basking in the monster’s ancient defeat, or worrying about warding it away. The Lunar New Year has metamorphosed into a time for loved ones to knit themselves back together momentarily, to eat and drink to good health, joy, and prosperity for the year ahead. From a celebration of fear, it has become, quite beautifully, one of community. Still, it’s fun to know that tradition has some meat in it, mythic or not.

Nearly all of my Lunar New Years have been spent with my mother’s family. They cluster into one amorphous bottled memory that feels preciously stoppered against the passage of time. It is memory characterised by the warm duvet covers in my grandparents’ study that I share with my siblings, by how my grandfather fusses over the air-conditioning to make sure we’re comfortable. It is my grandmother’s steaming bowls of savoury porridge in the morning; my grand-uncle’s dragon fruit jelly at the reunion dinner, where all of us are squeezed in at the kids’ table well into our twenties, a fate my youngest aunt only escaped after having her own children. It is the muggy heat of visiting the fish farm my grandmother’s brother once owned and doesn’t talk about anymore—the loss of a floating world a heavy one to bear. It’s the glass of the miniature aquarium in one of the apartments we always visited, a coldness I clung to in order to avoid making shy small-talk with relatives I hardly knew. It is the lalang grass we waded through outside my great-grand uncle’s house to pose for an annual family portrait; the faint, marbly musk of the columbarium where we paid our respects to my great grandparents.

I thumb through this memory album on the cold years I’m not able to spend with my family, like this one. The stitious side of me wants to lean into the rituals: to peel the oranges, put on the red, light the firecrackers, toss the yee sang, sit down to a meal with people with whom I share common ground, if not yet love. I want to do all of these things, and in the doing, to think about the why. To remember the myths that birth these rituals and how they cling to them still, even if not everyone remembers. To consider all the precious things the year gives and gives, the things we send back out to it in return.

Maybe there’s something in the image of a flame that refuses to be put out—that stays buried in a dragon’s throat for the precise moment it needs to arise—that plays sentimental tricks on the imagination. There is a beautiful poem by Jane Hirshfield called “Counting, This New Year’s Morning, What Powers Yet Remain to Me” that I’ve been thinking about recently. It begins with a question posed to us by the world, asking what we can make and do to change its brokenness. I feel somehow that it is talking about dragons. The poem’s last few lines read:

Stone did not become apple. War did not become peace.

Yet joy still stays joy. Sequins stay sequins. Words still bespangle, bewilder.Today, I woke without answer.

The day answers, unpockets a thought from a friend

don’t despair of this falling world, not yet

didn’t it give you the asking

This year, I want to light a candle that will not burn on both ends. A flame that doesn’t presume to wish for prosperity before it takes stock of the riches surrounding it. That holds grief’s hand without turning away from joy. That leans into the asking, sits with the question about what we can construct from ashes. I don’t know if I believe in fortunes told or withheld, in the idea of one specific destiny. But I do believe in spirit and soul, in the way the vessels that house them are borne and battered through insurmountable hurdles every day, and how still, we tend the flames, keep the fires burning. A match that’s mishandled has the potential to burn down the world, but fire is also what keeps us alive, warm enough to keep asking the question, to fumble for—and perhaps one day, muster—an answer.