A pixel fallen into,

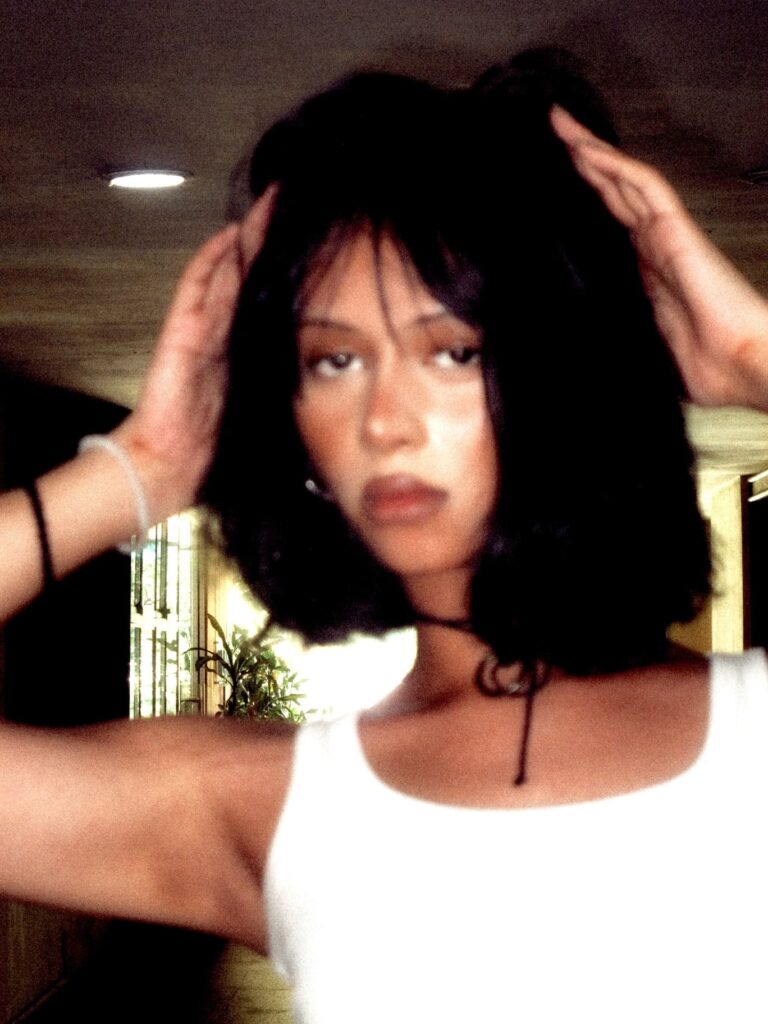

Beautiful, lean, hair cut with a knife, and the sonic-chic look composed of a small black blouse, and a choker made of ribbon, bowed.

She covers her mouth, “omg, I’m nervous!” screams out of a Bose headphone set.

Lidia Chatura is in the Zoom box.

“People know me as an artist.”

The room softens while the cursor scrolls upward to land on wings emerging in nude, fully grown hair sweeps across to hide their face; a feminine slim is drawn down to a modest phallus.

“I’ve always been drawing and making art,” she says stripping her father’s workbooks bare to enshrine them in doodles, of a child’s hand switching tabs to… “Oh, I’m also a model, a new model. I just started modeling a few months ago. And it’s been okay. It’s quite slow, but it’s okay,” epileptic flashes spray in pink across the screen.

“HELLO BARBIE!”

Currently, Lidia works as a model, retail associate, artist, and aspiring musician.

I first came across Lidia on Twitter (X) where she boosts 23k followers. There, she is openly Ms. she/her trans girl extravaganza eleganza but on Instagram and to a local audience, she blurs the lines of what it means to be a Woman. She tells me, “Some people cast me in shoots without even knowing I’m trans but I’m aware of my privilege to pass.”

who said transgirls cant have a BOB?😍 https://t.co/CxgLivPclI pic.twitter.com/Sa8Qil7tLD

— ليديا ꩜ (@222xen) July 20, 2023

I think it was Simone De Beauvoir who wrote, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.”

In the simplest terms (and to avoid plunging into the quagmire of theory), De Beauvoir consolidated that gender was a social construct. This is to say, a woman can only become a woman after birth by submitting to a language of rules which establishes a sense of identity. Later, Judith Butler would build on De Beauvoir’s theory by declaring gender as performance in Gender Trouble (1990).

Lidia entered the stage of womanhood with long waist-length hair; a poignant infliction of femininity in most societies, and definitely in a Southeast Asian/Malaysian context. She explains, “When I first started experimenting as a flamboyant gay boy in high school, I would dress more feminine by wearing wigs with a t-shirt.”

And well, hair is contentious whether it’s on your scalp, under your pits, or grazing your crotch; it is an archetype of any given identity; i.e. scene girl’s bird nest or school principal-cum-butch pixie cut.

It was for Lidia when she was finding her footing as a woman; at the beginning of her transition Lidia’s natural hair was very short, “the one thing I always fantasized about was having long hair like a princess. I didn’t cut my hair for 4 whole years. When it reached my butt, I felt pretty like I was at my peak. I felt like a woman with my long hair. I felt feminine. It was important. It made me feel comfortable.” But when I look at the woman staring back at me, she adorns a bob. And since our last chat, Lidia has cut shorter, sometimes sporting scarves or knitted beanies to cover her hair entirely.

Hair is a negotiation for Lidia; between dealing with historical constraints of feminity while creating new realities for herself. However, unfortunately for me, her chop wasn’t really a Britney moment… Still scary? Yes.

“At first, I was afraid, what if I looked like a man? What if I didn’t pass anymore? What if people start calling me slurs?”, she admits.

By the time she pulled the trigger or I guess, snipped her scissors, Lidia was already comfortable with her position as a trans woman. More so, Lidia’s transness wasn’t really about moving from one end of a ‘precise’ gender binary to another because as she says, “I never really cared about that.”

For her, transness is about daring to step outside of the confines, to grasp her autonomy, and of wanting more possibilities than the ones forced upon her. Trans as in transcend.

It makes sense then that her trans ‘awakening’ from a gay boy to a trans girl was propelled by musicians SOPHIE and Arca– “I was listening to SOPHIE and it just hit home. It felt like something and that moved me. Then I found Arca and she was talking about being both trans and non-binary. It made me question my position because everything she said resonated with me. Her music made me self-reflect.”

In an interview with i-D Magazine in 2020, Arca reflected on her journey of self-discovery, “I see my gender identity as non-binary, and I identify as a trans-Latina woman, and yet, I don’t want to encourage anyone to think that my gayness has been banished. And when I talk about gayness, it’s funny because I’m not thinking about who I’m attracted to. It’s a form of cultural production that is individual and collective, which I don’t ever want to renounce.”

In the same interview, she discusses the concept of her Kick series, a collection of 5 studio albums, “The first image that comes to mind when I think of the word ‘kick’ is a prenatal kick; that instance of individuation, that unmistakable moment where parents realize their baby is not under their control but has its own will to live, its impulses that are erratic and unpredictable, separate to their own. I think later we have a hard time distancing ourselves from authority and disagreeing with the top-down system that we perpetuate. So this is celebrating the moment of disagreement that is an expression of feeling alive. The baby doesn’t think about kicking, it kicks because it’s a vital impulse: no malice in it.”

For Lidia, these discoveries occurred during the height of 2019’s lockdowns. She says it felt like she was living in an alternate reality of being trans and non-binary all at the same time; she was owning her plurality online and amongst friends but eventually, as the saying goes, all good things must come to an end.

“When I stepped out into the real world, I felt the pressure. I was like fuck being nonbinary, I want to be a CIS woman. I want to have surgery. I felt the pressure to make myself look as feminine as possible. For safety reasons too so I wouldn’t get hate-crime… I needed to blend in.”

It’s been a lot of covering, uncovering, recovering, and uncovering again for Lidia. Today, she mostly expresses this through her drawings.

Her work features cyborgian creatures, feminine centaurs with robotic legs, female bodies with wings, and Michelangelo’s Greek penis.

In ecofeminist Donna Haraway’s The Cyborg Manifesto, she describes the cyborg as a “hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as creature of fiction,” that occupies a liminal space.

Lidia’s drawings are the classical prototype of this liminal (non)duality, not quite human yet not quite horse, yet not quite machine. Her work transgresses essentialism and disrupts the hetereocentric regime of the so-called ‘natural world’. She says, “I’m trying to normalise the trans body. That’s my artistic motive at the moment and I don’t think it’s a crazy idea.”

It is only the beginning of this epistemological warfare–of what it means to be and not to be all simultaneously… Maybe my school principal’s butch pixie cut doesn’t have to mean she is an anachronism of the patriarchal-misogynist complex, a failed sad copy of man but rather, a part of a new feminism where performativity contradicts realness and agency challenges production.

[EXEUNT]

Creative Direction by Alia Soraya, Jordan Chan & Pravin Nair

Pictures by Jordan Chan & Pravin Nair

Styling by Pravin Nair