Reflecting an island deeply rooted in the history of ‘drifting,’ the 4th Jeju Biennale explores, ‘The Drift of Apagi: The Way of Water, Wind and Stars’ capturing the complex internal world of Jeju Island, South Korea—its people, migration, and the rapid developments shaping its social landscapes. The concept of Drift in Jeju is liminal—existing between the island’s distinct yet intertwined identities.

In the midst of their contribution to the exhibition across various venues on the island from November 26, 2024 to February 8, 2025, Malaysian artist James Seet and Sabah collective Pangrok Sulap sat down with Mula to discuss the creation of visual documentation to avoid forgetting. Inscribed or in assemblage, these works allow patterns and connections to surface; a memento mori for drifting into something.

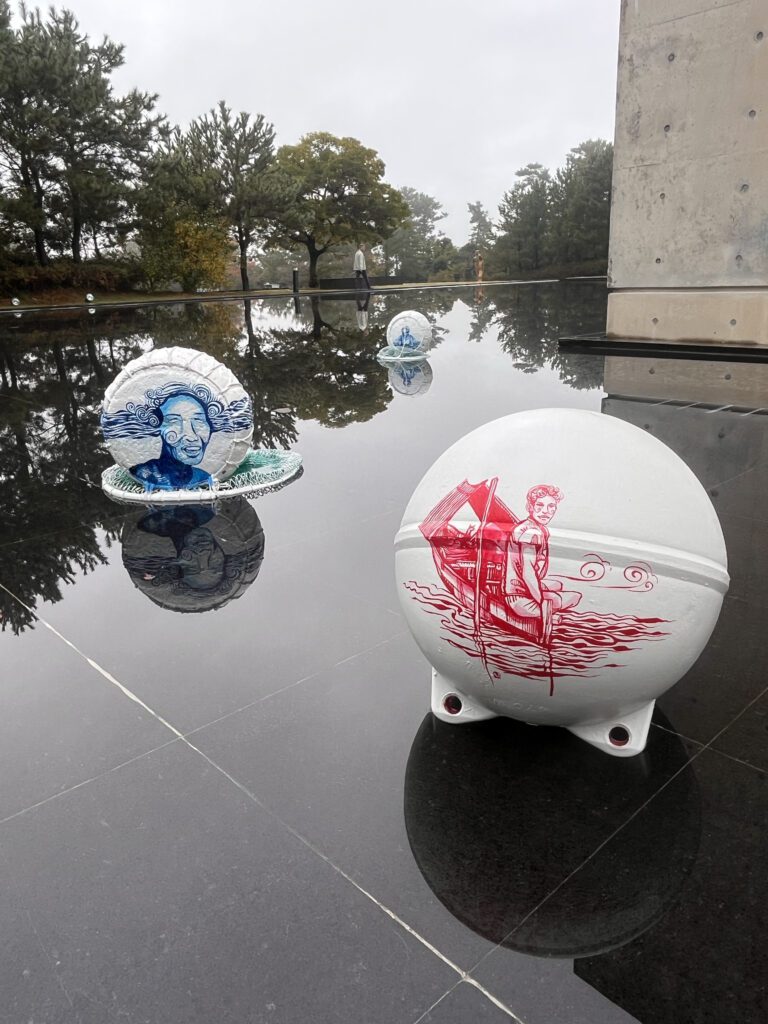

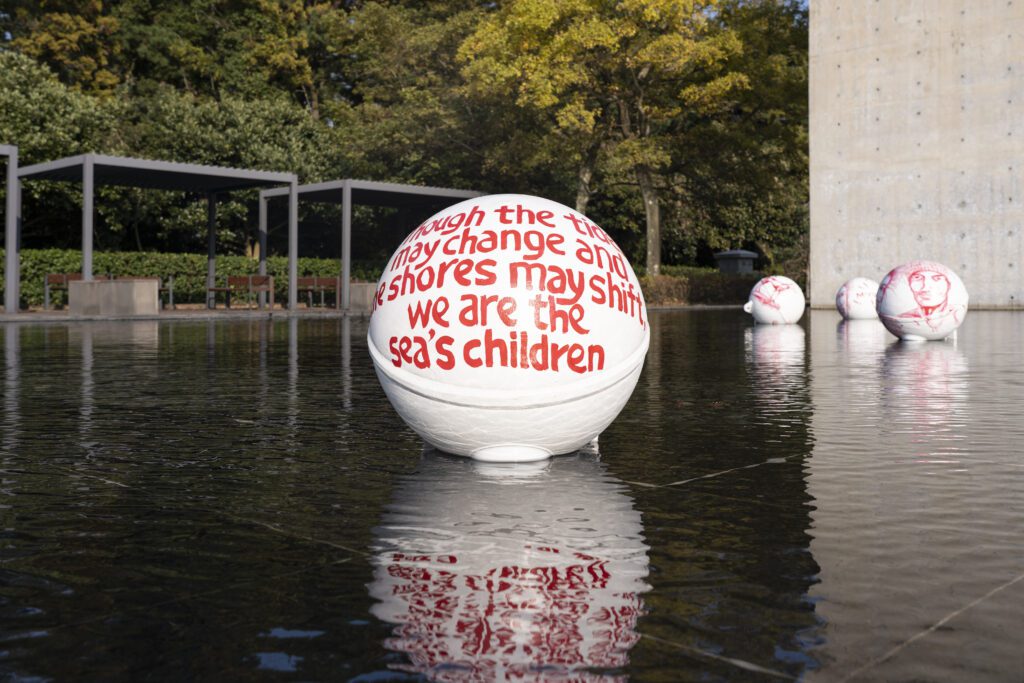

James Seet’s “Between Waves: A Dialogue in Red and Blue” features painted buoys that float across the water like time capsules in two colours– red and blue– colours in common between the Malaysian and Korean flags that symbolise the shared resilience and harmony of the communities Seet spent his time with: Haenyeo women of South Korea and Orang Seletar of Malaysia.

Haenyeo, Jeju’s female divers are known for their centuries-old practice of free-diving to gather seafood such as abalone, sea urchins, and octopus without modern equipment. This tradition, passed down through generations, is a emblem of strength, resilience, and cultural heritage. In 2016, the Haenyeo’s diving practices were recognised by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage. Beyond their diving skills, the Haenyeo are revered as key social figures in Jeju Island’s communities—a way of life that is now at risk of fading.

Likewise, Orang Seletar, the indigenous people of the Johor Straits in Malaysia have relied on the ecosystems of water for survival, changing against their watery landscapes where boundaires between land and sea blur to create a life of adaptability. Seet creates a link by juxtaposing these two communities. The artist showcases their shared reverence for the sea but also about the different ways to live together. Seet reflects, “I am realising, we may be separated by land, but we are connected by water.”

Seet tells a story about the dolphins who warn the Haenyeo of dangers in the water or the weather. He then tells me about how dogs are integral to the Orang Seletar way of life, a perfect symbiosis between species and nature. There is a dialogue between these two cultures happening– it’s why he placed Haenyeo’s actual buoys (taewak) against Orang Seletar’s scaled-up fishing buoys. These buoys float close together, far apart, toward and not just away from, highlighting a holistic way of living where water represents the continuous flow of time. A flow that carries fragmented memories and promises, defying a sense of permanence while still holding onto what has been and the potential of what is yet to come. The buoys are in constant motion, water shaping the landscapes it touches and the lives it sustains.

It is both ephemeral and eternal, always in flux, never existing fully in one state. Water, like life itself reminds us of our impermanence, our connection to the earth, and the cycles that continue to overlap, never entirely separable. Seet says, “They are so in tune with nature so they don’t harm the environment. Actually, you know in the name of ‘progress,’ we often harm our environments more.”

Also focusing on this sense of connection within the concept of ‘drift,’ Pangrok Sulap, a Malaysian collective of artists, musicians, and activists, created a woodblock print series titled, “Honor the Past, Treasure the Present” through their own personal and cultural lens, reflecting on their experiences as artists from Sabah and Borneo.

Since their formation in 2013, the collective has used woodcut prints to amplify social messages, focusing on rural life, endangered traditions, environmental issues, and themes of human rights and political corruption. With a strong DIY ethos, their slogan, “Jangan Beli, Bikin Sendiri” (Don’t Buy, Do It Yourself), underscores their commitment to self-expression and grassroots empowerment. For Jeju,the artists created seven woodcut panels that explored the island’s agricultural practices and heritage with each panel delving into different aspects of Jeju life while examining the intersection of tradition and modernity.

Their work is a tribute to both the past and the present, capturing how local communities in Jeju honour and preserve their culture, something they felt was lacking in their own country. The collective draws parallels with indigenous practices in Borneo, particularly types of shamanism, which holds deep cultural significance for them. They emphasise the importance of experiencing a place firsthand rather than relying on internet research, as direct engagement helps bridge the gap between theory and reality. Their approach is rooted in respect for both the cultures they encounter and their own, ensuring that their work honours the traditions and histories of all involved. Pangrok shares, “We’ve been working together for over a decade, around 13 years now.

Our roots are in the underground, punk rock scene, and we come from a radical movement before we became artists. We embrace anarchism and the DIY spirit, believing strongly in self-expression and independence. We chose woodcut as our medium because of its historical association with propaganda, which aligns with our belief in using art as a tool for social change.”

When asked about incorporating shamanistic rituals into their work, the collective reflected on the differences between the practices in Jeju and Sabah. While they didn’t visit the shaman communities in Jeju, their research revealed a joyful and celebratory approach to Shamanism there, contrasting with the more solemn, ritualistic practices in Sabah. Despite these differences, both cultures share a belief in animism and a deep respect for nature, with sacred sites like Jeju’s Hallasan and Sabah’s Mount Kinabalu. They felt that the spirit of Shamanism, as guardians of nature, resonated in both cultures, influencing the way they approached their art.

Connection is at the heart of both Pangrok Sulap’s and James Seet’s contributions. They embody a rich exchange between tradition, modernity and cultural preservation. Through buoys, woodcut panels and a collaborative approach, the artists celebrate and honor the unique traditions they encountered in Jeju and beyond. As Seet shares, the goal is for the younger generations to view their heritage and its relevance in today’s not as something fading, but as something to embrace and keep alive. They hope their work helps bridge gaps, opening conversation about how we can preserve traditions in a rapidly changing world. For the collective, the art itself serves as an invitation to engage and reflect, leaving space for interpretation while celebrating the diversity and richness of cultural identities.

Pangrok says this culture is important because it is the very foundation of identity—it shapes our language, music, food, and philosophies. It’s important because it binds us to our roots, defining how we experience and interpret the world. In their words, without culture, we are nothing; it is through culture that we maintain our authenticity and connection to our heritage, whether in Malaysia or Jeju. Culture transcends boundaries, even the spiritual, and creates a sense of belonging wherever we are. As they express, “When you meet someone from your homeland abroad, you instantly connect, knowing that shared culture is what unites you”—a common language, a shared taste, and a deep understanding of the world through the lens of your traditions. It’s this connection that shapes everything, from our identities to the very way we engage with the world around us.