If there’s one thing that I really enjoy doing besides being immersed in a really good story, is that I love telling one. And since I’m being given the time – and space – to tell this story, to that, I will. Let me start at the beginning, with my editor and an album that changed the narrative of how I viewed everything I created with my bare hands. Sometime in the middle of a hot March evening, I received a text message from my editor, who needed some help with a pitch deck.

“Prav, can you help me out by re-wording this? It just needs to be easy to understand.”

The task at hand was simple: articulate existing points, simplify everything, and make the pitch deck engaging. I didn’t mind doing it. After all, I had nothing special going on at this point in time. When March rolled around, I had left my job as a copywriter in an advertising agency and decided on focusing my time as a freelance writer instead. For as long as I could remember, I had felt like a fish out of water the moment I graduated. Having unwittingly taken on a degree in Marketing (that I found to be disinteresting) at the behest of the adults paying for it, I felt like a wrongly placed puzzle piece in a larger picture.

I had always intended on pursuing a degree in literature or in English and thrusting myself into a life of storytelling. But the thesis of life is never as you wish it to be. Not everything falls into your lap like a fairytale or a Disney movie. The fact of the matter is hard work and constant pestering of individuals can get you somewhere. And that’s how I got here, writing this essay on how one should Come Home, and Eat.

Now That I’m Done, Won’t You Come Home and Eat?

The day had finally come for me to meet Chloe, the production manager for the play. After a series of long-winded text messages from my end and planning, I was ready to meet the woman managing the play. Now, you’re probably wondering why I’ve been insisting on eating at home. Let me quickly clear the air before I begin preaching my story. Titled “Come Home and Eat”, stories are strung together and brought to life from thin air.

The creative process of making something exemplary out of nothing, whilst not unfamiliar to the creative scene, affirms a shared sentiment upheld by creators alike – art and creativity will always persevere. When given the space, time, and opportunity to create, wonderful outcomes present themselves. This is especially apparent with Come Home and Eat. I had decided to take the bus the day I was supposed to pay Theatresauce a visit. And in true fashion to my life, nothing had worked out the way I had intended it to. I began my day by attending a sample sale (as we all realistically do) and decided on taking the train to KLPAC as it was the most, obviously affordable solution. Having picked up my lunch (with a side of RM3 mangoes), I marched toward the Ampang line at Salak Selatan and hopped aboard the train.

This was when things decided to go downhill for me. At this point in time, I had been taking multivitamins that were upsetting my stomach, the train lines weren’t working all the way leading me to take a bus to KLPAC, and the walking (which I didn’t mind) was unbearable with the haze and heat of the day. But when I did finally get to KLPAC, I was greeted by Chloe. Warm and welcoming, she led me through a series of back doors and flights of stairs until we finally reached a room on the top floor. As we finally sat down and began our little chit-chat, I began to notice how prepped she was as a production manager. Walkie strapped to her waist, phone buzzing away with texts from artistic director, Kelvin Wong and the tapping of both our feet.

“Tell me a little bit about yourself”, I asked her. She responds eloquently.

“Hi. My name is Chloe Liew. I’m 23 this year and I’m a contemporary music graduate. I’m currently working with Theatresauce as a requirement for my internship and I have been tasked with managing and assisting two productions. One of them is “Come Home and Eat” and the other is “They All Die at The End”. Each of these plays is brought to life through devised plots”.

Not knowing what this term meant, I asked, “What do you mean by devised plots? Could you explain that a little further?”

She explains simply and astutely by saying that the members of the play essentially come in with the least number of ideas – in some cases, almost nothing – and begin to build a storyline together. The plot of the play is tethered together by stories, ideas, and experiences are brought together. In the case of Come Home and Eat, the actors and artistic director, Kelvin Wong embedded their personal experiences into the plot of the play. “Would you say that this is more so a collective process?”

I asked her. She affirms my question and adds that the ideation process was not limited to the actors, but rather welcomed the ideas of everyone else who a part of the show was. Breaking the devised plot into the four phases that Theatresauce employed to birth Come Home and Eat, Liew explains, “We begin with building, sculpting, chiseling, and the final run-through. We had a total of forty stories that we had collated over time since beginning in January this year. Wong had to make the decision on which one’s stayed, and which had to be chiseled away.”

Liew explains that her time at Theatresauce was more than she could have asked for. Beginning her internship in January in a performing arts company was a step away from the typicality of her life. Being a contemporary music major, who specialized in vocals, the leap into the world of theatre, while daunting, felt almost natural to her. Looking at her performing her tasks from an outsider’s point of view – where she dealt with media personnel, ticket sales, managing props, and food items, and even showing me around while being able to answer all of my questions – I couldn’t help but wonder that maybe she was born for this role. Before I could finish interviewing Liew, our conversation got cut short by a series of rapping noises on the door.

“Is there someone we’re expecting?”, I asked.

“No. Kelvin isn’t here yet”. Liew replies.

She heads to the door and opens it to reveal no one standing in the doorway. That was when I learned of the hauntings that took place in KLPAC. While there’s not much about it online, Liew stories me about how things get flung around, unexplained knockings on doors, and eerie noises being heard by actors, stagehands, and production crew members. I didn’t want to dwell too much on the idea. It wasn’t that I was spooked, but rather had a sharp aching pain in my belly and an assignment to finish. It just so happened that Theatresauce’s artistic director arrived at that very moment.

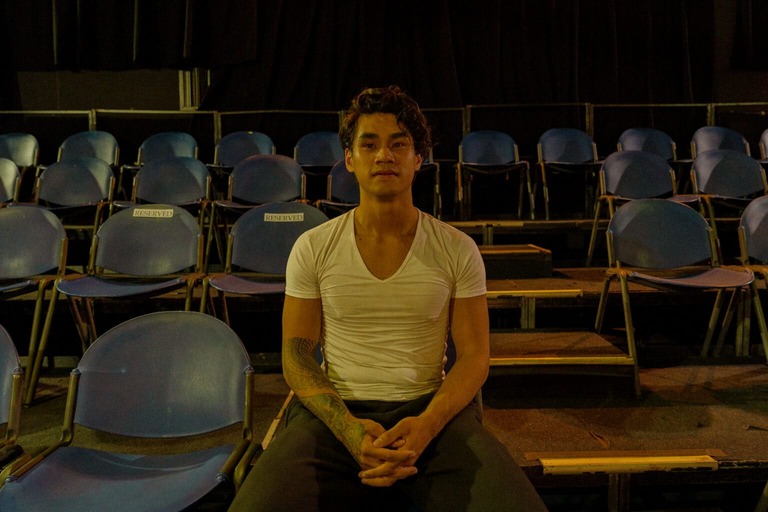

So, we both packed up and went to the entrance to greet Kelvin. Dressed in a polo tee and turquoise shorts, Kelvin was breathless as he walked into the event area. Following him backstage, he suggested I sit in with him while they did their final checks. It was, after all, opening night. There were stakes at hand and everything had to be perfect. Witnessing the entire run-through with lights, sound, music, and graphic visuals on screen, I was wowed by how collaborative it truly was.

“Add a question mark here”

“Jaz, can you change the order of this?”

“This one right, can you put f-ing disgusting and put an arrow pointing to the guy?”

“Oh, this might not work, can I suggest something like this instead?” replies Jaz, the projectionist designer. And with that, Wong agreed to the idea, and they progressed forward.

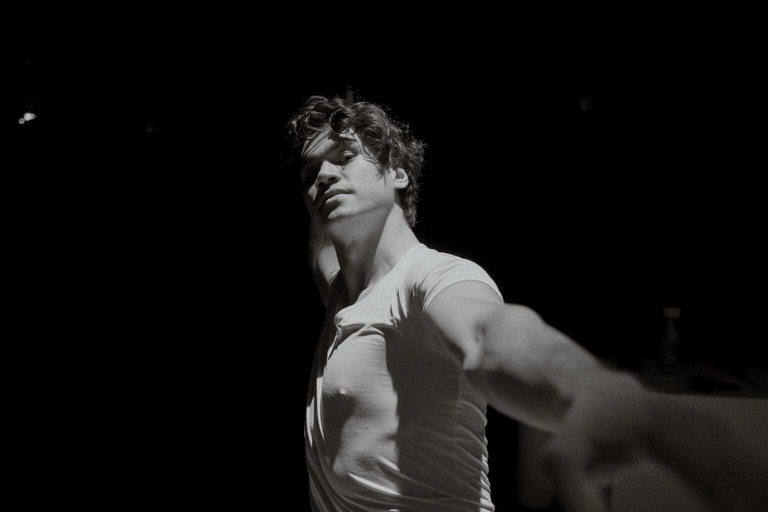

As I sat there in the dark hall in silence, watching the last of the prep work take place before me, the actors of the play began appearing one by one. With no opening night jitters scattered across anyone’s face, I was sure that the play was going to go well. And come Sunday afternoon, when I finally sat down to peer into what Come Home and Eat was really about, I understood why everyone bringing the play to life remained calm and collected.

On the day of, I was invited to Come Home and Eat

Arriving at KLPAC on the 13th was smooth as it could be – my Grab driver took an excruciatingly long route to the venue. Having kept Yasmin – my friend and videographer, and Haziq – the photographer at the venue waiting for 20 minutes, I apologized profusely as we pulled up. Having figured my way around the backstage area, I ushered my two partners to be acquainted with Liew.

“How was the show on Thursday?”, I asked Chloe.

“It went really well. This evening we’re going to be playing our last show before we move on to the next play”, she responds.

I was glad to attend the matinee show – purposefully chosen so that I could have

- enough time in the evening to pack my bags for my trip

and

- and stay away from large crowds.

Only the former took place. Even on a lazy Sunday evening, the hall was filled, leaving only a few seats unoccupied.

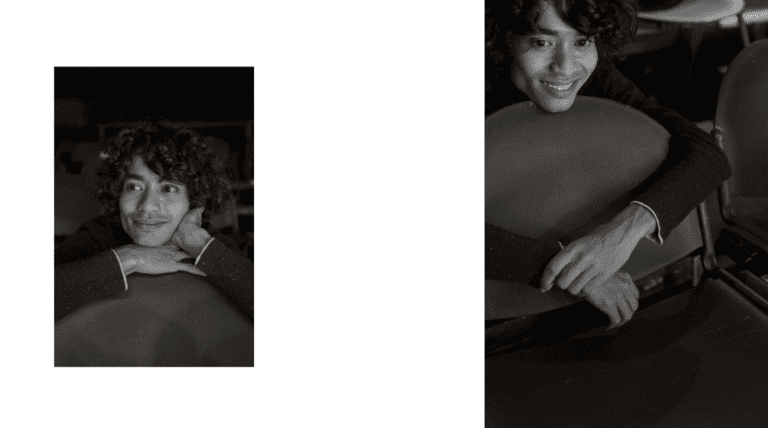

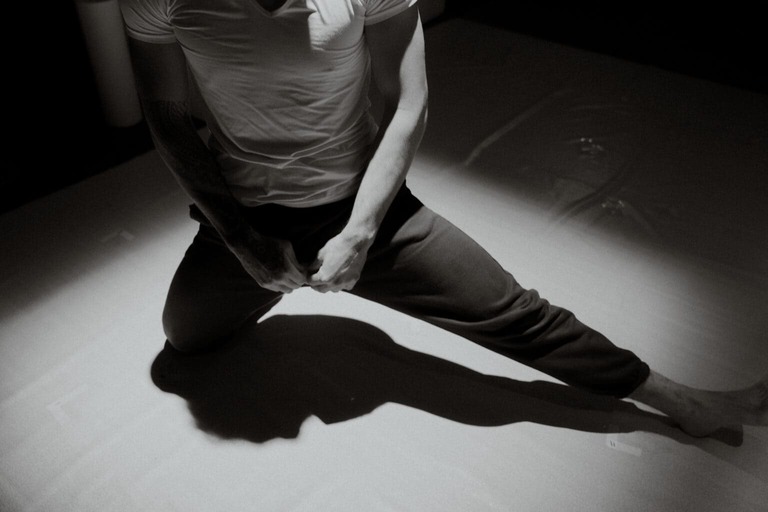

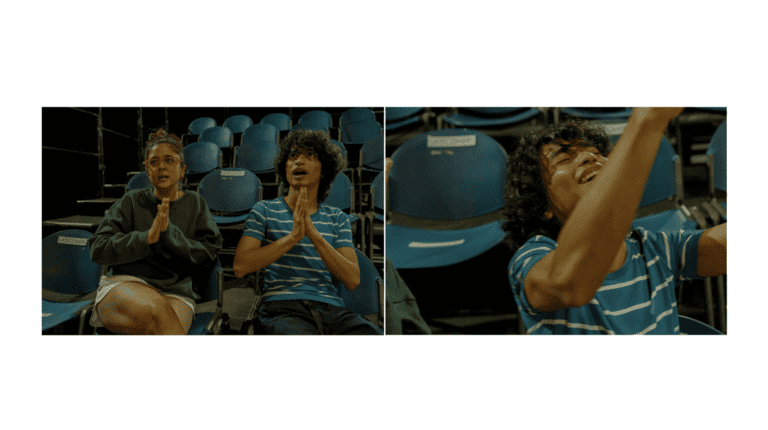

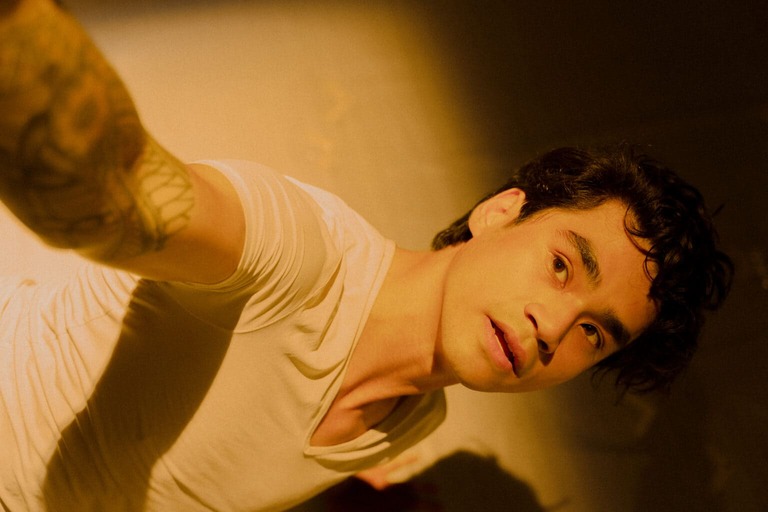

Before we took our seats, Haziq, Yasmin and I went around the stage and seating area, introducing ourselves to the actors and having their pictures taken. Trying to set a cool and calm ambiance for the photoshoot, the actors, had no qualms about being turned and posed in a multitude of ways. Pliable as they were, I was now beyond excited to see what they had in store. at 2:45 P.M., the Mula crew left the stage and went back out to the box office to once more queue back to our seats. As the audience members filed into the nearly full house, the lights dimmed to spotlight the seven actors seated on the floor by wooden blocks resembling tables. With food splayed out before them and solemn looks on their faces, a bell rings and they all lift and make way for their first scene. The play begins with something hitting close to home: my apprehension of speaking in Tamil out loud in public.

A legal editor by day, and actress by night (and on weekends), Kamini Senthilathiban steps out on stage and begins her monolog on her disjointed relationship with the Tamil language. But before her voice echoed through the hall, we were greeted with a projection – Wordle style – on how one should be ordering items at a banana leaf restaurant.

“Anne, rendu appalam yeduthuttu vanggeh?” were the words etched on the screen. Accompanying it was the words written in Tamil scripture and a translation in English. “Brother, may I get two applaams (pappadams) please?”

This is how her story goes: On Pongal morning, Kamini stood around the Paanai (pot) with her immediate family members waiting for the rice to come to a boil. As the moment approached, she couldn’t find it in herself to utter the words her family members were cheering on. “Pongalo Pongal”. When questioned by her mom, she simply stutters and drops the conversation entirely. This is a feeling and ineptness I felt while seeing a story so familiar to me. Growing up in an English-speaking family. That meant my communication skills in Tamil were abysmal. While I am able to speak it, as fluently as I am able to today, I am stumped by the fact that my conversational skills are not up to par. That was what Kamini followed up with – a feeling of embarrassment with not being able to communicate in one’s mother tongue.

But then, she follows up with her mothers’ black Halwa and how with each passing year, though never getting it right, her mother’s perseverance served as a guiding emblem to always keep trying, even if it meant that you weren’t good at it. This “almost” diasporic sentiment was one I have held close to my heart. Belonging – and yet – somehow never being fully allowed into the club. Sneers, laughter, and the ever-so-snide comments about how I sound “white” while speaking in the language that is my birthright left me with the need to silence my voice, tying my tongue in my mouth, and abandoning it. But like Kamini, and like the ever-effervescent Samantha Jones from Sex and The City, I say, “If I thought about what every bitch was saying about me, I would never leave my house!”. And just like that, like Kamini, I tried again.

As the play went on ascending, touching on subjects surrounding Western tourists plaguing Southeast Asian streets with their very prejudiced comments on our delicacies, audience members were halted to reconsider an alternative to our apparently, “gross” cendol or oily and greasy curry noodles and Nasi Lemak. Presented as the second story by Sharanya Radhakrishnan, Nabil Zakaria, and Ryan Yap, the theatre hall transformed from Kamini’s kitchen into an aircraft cabin. Donned in scarves around their necks, the three actors vocalized their opinions on Western prejudice towards Asian delicacies whilst visiting, say, Malaysia for instance. As the monologue dies down, we are kindly greeted with a tongue-in-cheek dig toward Singapore. “If you had this much to say about our food, we hope you enjoy what Singapore has to offer”, is what I can loosely recollect Sharanya saying.

With each passing minute, stories developed, peaked, and seamlessly slid into the next one. With topics of eating disorders being discussed by Yap, an entire monologue narrated by Zakaria in Malay on his growing appreciation for food and the relationship mother, a first chicken POV of it being slaughtered and made into Hainanese Chicken Rice by Nicholas Augustin what truly shook the shook me by force were the two monologues done by actresses Nephi Shaine and Farah Rani. Slid between the flight scene and the one discussing eating disorders was Shaine and Rani’s take on the strained dynamic between a worried mother and her queer daughter. What stood out this piece of acting was how the two actors remained silent, making dumplings, while their older counterparts argued on screen. As portrayed on the screen above the actors, Rani (mother) and Shaine (daughter) took on their roles and perfectly tiffed on screen like any and every other parent-child relationship. Happening on her brother’s (Yap) wedding day, Shaine decides on revealing to her mother that she will, once and for all be returning back home to Kuala Lumpur to begin a career in teaching.

Shocked and appalled, Rani bursts into a dizzying state of both anger and disappointment.

“Girl, you don’t get it, Michelle Yeoh had to leave Malaysia only then she could make it to where she is today!”

“What nonsense are you talking?!”

“There is no place for you here”

These were the words I could recall Rani saying to her supposed daughter. Hurtful as it is, and as accepting as she was to her queer daughter – wanting her to carry on a relationship with a woman in California – I couldn’t help but wonder about the strained tenacity in which parents communicated with their children. While I never had a perfect relationship with my mother, words, and sentiments like these were thrown around day in and day out. As Rani and Shaine continued their argument on screen, the real-life individuals continued making dumplings. You know that saying about how Asian parents can’t say that they love you, but instead will cut fruit for you to show affection? Yeah, that’s what was happening here. As Shaine’s “brother”, Yap, went out playing soccer, a grumpy Shaine was forced to stay at home to make dinner with her mother. Not much is said or implied as to why – but a lot can be heard if one uses their eyes to listen and understand.

Questions pounded through my mind.

“Did she have to stay at home ’cause she’s a girl?”.

“It’s no wonder she looked so annoyed, my God”.

“Hey look, her mom is being nice, she’s patiently teaching her daughter how to fold those dumplings”.

In the end, on-screen, both mother and daughter ended their conversation in the typical Asian household screaming match and the ever-familiar, “Don’t come back home, you don’t belong here. I don’t want to ever talk to you again.” These words are familiar to me. An experience like the one I had just watched, took place, word for word, in my own life. Moved I was, by how similar things can be, how stories repeat themselves and then, like magic, become so different when it’s applied to the next person.

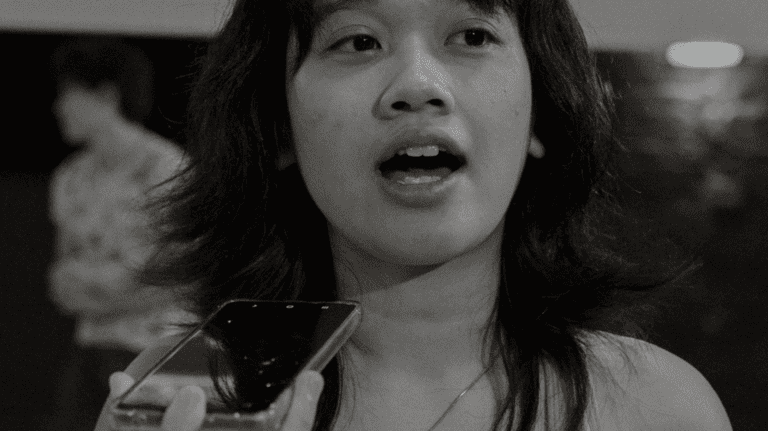

Ending the play, Rani takes centerstage with a monologue on solitude. Having lost a close friend, she narrates the past, painting memories by using hand gestures and setting scenes through a descriptive manner of language. And there I was, sitting there, and realizing, I was yet again, relating to a story. The stories of loss and the ways one grapple to make sense of things. How memories stay floating in time, living on in spaces and serving as shrines for what once was. Right before we are brought back into reality, Rani reads from her phone, citing a message that was delivered by her mother. As I recall, it went on like this, “Girl, come home and eat lah”. As I had “the” moment of realization when individuals noticed the use of the title in the movie/play (I had a similar one when watching Cat on a Hot Tin Roof), the cast members pulled up and gave a bow. As Yasmin and I left our seats and headed home, I couldn’t help but wonder about the conversation that I had with Wong hours before opening night.

Recorded entirely on my phone and on paper, I skimmed through the audio file first. Listening to the 15-minute conversation between Wong and I revealed how I had a part to play in the play after all – just now how one usually does. In the grand scheme of things, as Wong puts it, creation is a natural part of the human condition. As we shared our personal experiences with each other, I came to learn that Wong’s true passion was being realized day in and day out with his commitment to Theatresauce. First partaking in theatre when he was in college, Wong intended then to pursue a degree in the performing arts – an idea that was shut down by his parents instantaneously. Unencumbered by this reality, Wong then pursued a degree in psychology and to placate his interests in the meantime, he founded a theatre club at his university. Eventually establishing himself by approaching the founding members of KLPAC, Wong was offered to become a director in residence. Eventually moving on from said position to work on Broadway and pursue his studies in the performing arts, Wong shared that he found the need to come home.

Listening to the director speak, I couldn’t help but admire his perseverance in pursuing a craft that he found to be, loosely putting it, his calling. “Ever since I was a kid, I loved cooking up and creating experiences for those around me. It’s funny and endearing that this is what I do now”, he says. Before we wrapped up our conversation on Come Home and Eat, we talked about the need to create and persist through change. Having troubles and tribulations around my own career as a writer, I asked what he thought about it, and this was what he has to say:

“Love what you do. Your time will come. We can say that we love the things that we do, but in reality, you need to re-evaluate the reality of things, when shit gets tough. Ask yourself, if you love what you do, and that is how you will find success in your field. Hard work is necessary too, but loving, well that’s the thesis in doing what you love.”

On my time away recently, I began thinking a lot about what Wong had to say and how the people in my life, my editor, especially, have been the reason behind me loving what I do. I have never seen myself as a creator, a maker of things. I remember our first conversation happening almost five years ago, how I eagerly insisted on publishing a poem and after a few edits, it went live on the website. I have been steered by the mariners in my life, namely my editor, Alia. Coalescing the sentiments to Come Home and Eat, where discussions of heavy and light-hearted topics all took place around meals, I began to see the need for community. I have come far in this life. From dust, I will pay my dues someday, but today, I’ll just reflect on the actors, their stories, food, and my love for my best friend, my editor, who has allowed me to find love in what I do.