Like Lippard, I Woke Up late, with no real birthright to awareness education. The social consciousness I gained from my parents was one of a religious sort to treat everyone with kindness. My revelatory experiences came after University, living in the first world’s third world equivalent when I immersed myself in London’s active art scene from 2016 to 2019. There I learnt the art of protesting and the term, reformative action, which surfaced again when I returned to Kuala Lumpur’s multiculturalism in 2020. I felt burdened by the social order’s naturally accepted prejudice. Like Lippard felt in 1984, “isolated art for art’s sake had no place in a world so full of misery and injustice,” I feel today… It is March 2024.

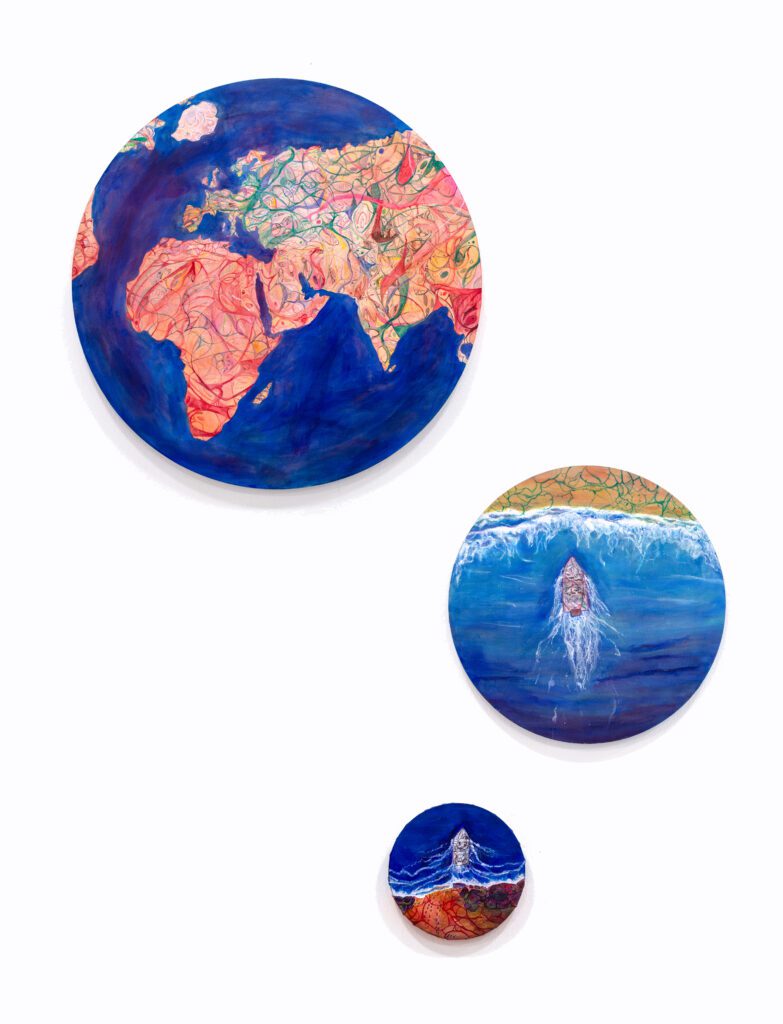

Portals of Longing assumes a liminal self, logging precarious transformations in spirit, and purpose, to animate the contemporary struggle of refugees in Malaysia whose lives are often considered peripheral to the city, the nation-state, and wage relation. Drawing on lived experiences in Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Palestine, Syria, and Myanmar, the Artists map dreams between worlds, grasping onto murmurs of history to uplift their culturally personal legacies. Fluctuating between moods and forms of movement unregulated by a state that accompanies their life in a ‘post’ world crisis,’ Portals of Longing channels the only sense that is certain–– yearning.

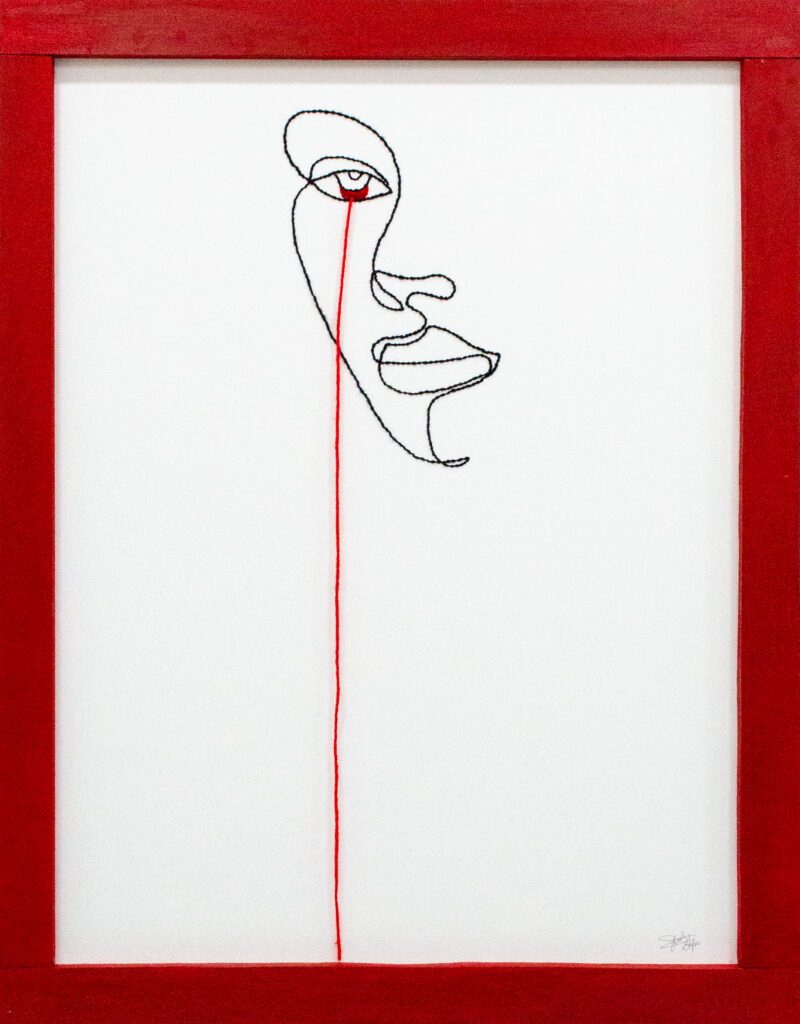

A woman waits for a son, a husband, and a brother to return in Nour Aldeen Salem’s painting, ‘Diaspora.’ Her black and white image caresses a belly mapped out in droplets of red for the far-away sites bottling up her only blood type. She symbolises, as Salem puts it, “the greatest suffering of all” in a world inundated with forced choices. In the artist’s home Syria, male counterparts often face compulsory military service, urging them to move elsewhere. Salem found out he had to enlist to fight in a war just 15 days before… His mother waits, for 10 years, hoping her son will visit.

I ask Salem if she has seen ‘Diaspora’– “Actually I didn’t show her the artwork because if she sees it she will cry much more,” he replies.

The international and legal definition of ‘refugee’ generally refers to people fleeing conflict or persecution for going against reasons of race, religion, nationality or political opinion of their country of origin. This act avails the refugee of his nationality and so, protection from the country. Still, in Malaysia, there is no formal framework for refugees and they are not legally defined nor, protected by law. This is to say, Malaysia exists as a legal no man’s land where refugees are vulnerable to exploitation and are often treated akin to undocumented migrants, vulnerable to targeted and official crackdowns.

For some of the 187,020 refugees and asylum-seekers registered with The UN Refugee Agency in Malaysia since February 2024, viability is neither here nor there. Being uprooted from their national communities implies a loss of one’s identity, culture and traditions, dissolving their sense of personhood. This leaves some refugees without agency and limits them to a bare life; in which the sheer biological fact of life is given priority over the way a life is truly lived. It could be said that the refugee’s limited existence is confined within the boundaries of a systemically defined ‘refugee’ existence.

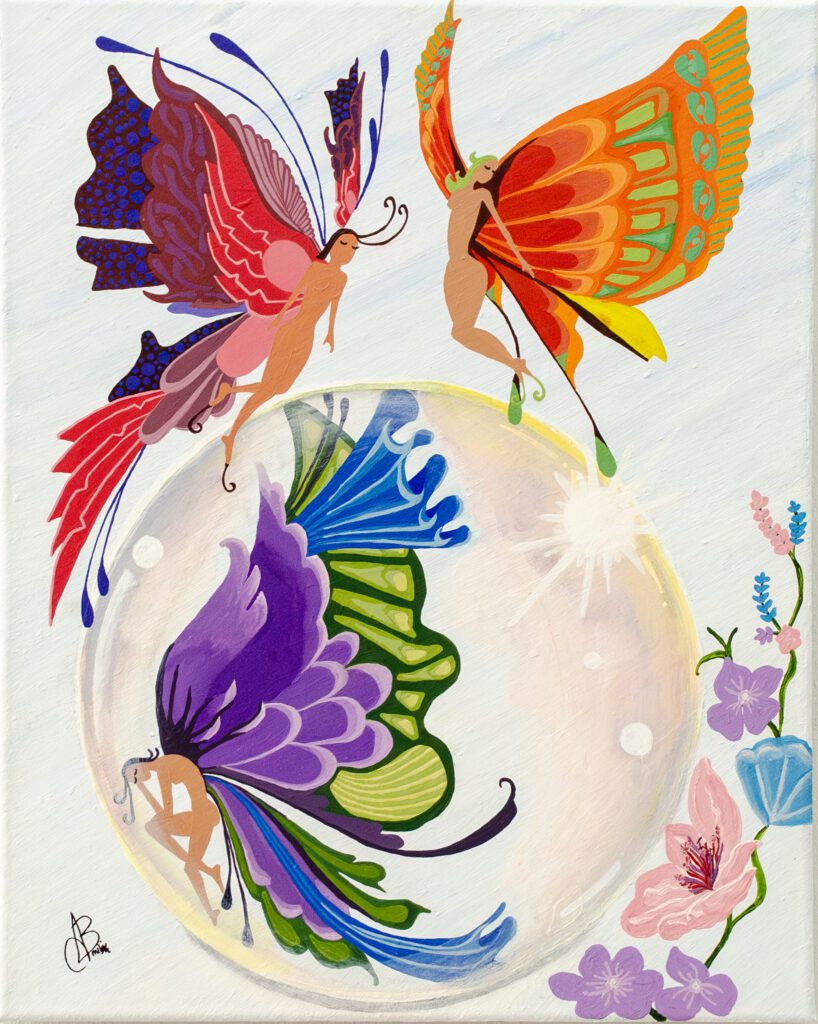

But Malaysia was the only country that would take Salem on such short notice even if that meant Salem had to give up his primary vocation in physics once he arrived. Instead, he learnt graphic design and now practices as a freelancer– much like the father-daughter artist duo, Abdurof and Reham Baydoun, artists of ‘Timeless Odyssey,’ who say freelancing is a sort of saving grace when 9-5’s are not an option.

Reham, an architect and her father Abdurof, an artist also paint a woman– one who is relentless in her pursuit to safe-keep national legacies while vying for tranquillity across borders. Carved in a traditional Syrian decorative design technique called Ajami, ‘Timeless Odyssey’ focuses on the migrant woman’s journey through the long history of human civilisation. A horse, flowers, mosques, and churches trace the intricate identities of coexistence. Birds of peace soar above symbolic landmarks like the Twin Towers to represent the artist’s journey to Malaysia. Reham makes a joke that the painting may seem “crowded.”Yet, it is in this beautifully illustrated chaos that we see the manifold experiences of a refugee’s life, even if bounded to a limit. In one way or another, the works in Portal of Longing are a visual documentation of a particular story. Whether a hero in Baydouns’ portrait of the woman or Ahoora Jenab Zadeh’s more fraught sculpture, ‘Crossing the Rubicon,’

An astronaut floats in the middle of four hands where an alien sits, facing this astronaut. Behind this astronaut is a perfected man who celebrates a victory– a 13-year transit through assimilation. Except, they are all in white. Zadeh’s ‘Crossing Borders’ reflects the many perspective’s of one man’s journey through migration but most of all, depicts the sense of alienation from not just his surroundings but his being as well with the purposeful use of white acting as a blank canvas of sorts, a void. Zadeh explains,“Becoming a refugee was a means to an end. We know we cannot return to our country of origin but when we enter here, we cannot help but be distracted by the fact that we are finally safe from the place we are running away from. We think we are safe because if we are running away from conflict if we are running away from persecution… But the longer we stay here, we realise that there are issues in and of being a refugee in Malaysia. That slowly chips away at the concept of hope as we know it.”

*

After I end the interview, I get into a Grab to head into the city. On my way there, I pass a football stadium with the words, ‘FREE GAZA’ spray painted across the field. Young children are carrying the Palestinian flag and my Grab driver is tuned into a radio station looping Islamic prayers for the women, the men, and the children being attacked. The disparity between historical narratives and personal experiences has never been more clear.

Portals of Longing escalates and intensifies the semantic gap between the representation of violence and the experience. As Zadeh tells me, it is not that people are not willing to understand refugees but currently, a limited widespread understanding of refugees permeates Malaysia’s social cognition. He says, “Sometimes when I mention I am a refugee, people’s initial response will be, ‘Oh but you speak English so well’ or ‘you’re educated,’ ‘you’re doing something with your life.’ There is an ignorance of being a refugee and the refugee experience as a whole.”

There is an intersectionality to these issues, to why we support and to whom we lend our support. The artist’s first-hand reporting helps dismantle biases, calling into question the materiality of being and the very real collateral of war; its people. As Zadeh tells me, “I want them to feel even, a semblance of my pain” because people rarely learn by listening, they learn by experience even if, through observation. Zadeh agrees, he doesn’t expect people to empathise but to cultivate sympathy through understanding one’s internalised level of pain that can sometimes only be expressed through the interiority of art.

Art is an expert witness.