But clothes play a more sinister and ponderous role in the film than just wistfully outlining the slender contours of Mrs. Chan’s loneliness. Velvet house slippers, snappy ties, ornate cheongsams, red coats—even delicate pink handbags with soft ruffles bring with them their own moments of sumptuous significance.

We might begin, rather unconventionally, with the ties. ‘That tie looks good on you,’ Mrs. Chan tells her boss, a kind-faced elderly gentleman who we soon learn is cheating on his wife. It is an affair that Mrs. Chan condones, and in fact, somewhat authorises: she parleys phone calls between him and his unwitting wife, transmits messages, and delivers surreptitious gifts between paramours. When he tells her this new tie is rather like his old one, she casually remarks: ‘You notice things if you pay attention.’

Does she refer here to the claustrophobia of Hong Kong, the palpable feeling of being watched that pervades the film? Or perhaps she is talking about picking up on the encroaching period of auto-decolonisation in Hong Kong, one alluded to near the end when Mrs. Chan returns to Mrs. Suen’s apartment, and the old landlady says, ‘It was so nice then, wasn’t it?’. Does she mean that she herself is growing steadily aware of her husband’s infidelity, beginning to notice things by paying attention to his behaviour? Perhaps it is then also a word of caution on her part, warning Mr. Ho to be more subtle in his infidelity if he wants to keep it under wraps.

It’s nice to think that it could also be a meta-cinematic comment, urging the viewer to note how painstakingly each article of clothing is selected, how specifically representative they are, and how wonderfully imbued with artistic significance. Wong, characteristically cryptic, and ineluctably ambiguous, leaves this remark open to interpretation.

When Mr. Ho changes his tie later, he tells Mrs. Chan it is because the other one was ‘too showy’. Her words, however casually meant, are heeded.

There is another memorable scene with a tie when Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan meet for tea. Sipping foamy drinks from cups the colour of mint, their conversation is stilted and polite, spurred mechanically on by the stir and tap of silver teaspoons. What seems like an exchange of niceties becomes laden with intent: he asks where her handbag is from, claiming he would like to buy one for his wife’s birthday, but in a different colour, she urges him, because ‘a woman would mind’; in turn, she questions him about his tie, saying she thinks it would become her husband. They exchange similar answers—that their spouses bought them on trips abroad—and marvel at this seeming coincidence. Then, the tea abruptly abandoned, Nat King Cole’s sultry, almost mocking song cutting off just as suddenly, the pair admit to one another that they’re asking only because his wife has the very same handbag, her husband the very tie.

Clothing, like with Mr Ho’s tie, becomes a traitor of filial disobedience, and perhaps also its signifier. One cannot help but recall how, when asking her husband to buy a tie for her boss’s wife and his mistress, Mrs. Chan tells him it doesn’t matter if they are the same colour—‘Who cares?’, she says smoothly, because after all, the two women will never meet. If your husband is consorting with your neighbour, however, it would matter; you would—as a woman—mind.

Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan’s perceptiveness, fervent awareness of their surroundings, and attention to detail are perhaps made manifest in the particular care awarded to their dress. Tony Leung is, as usual, resplendent with slick-backed hair and dapper grey suits, perhaps ever so stylishly creased in places. Maggie Cheung shimmers in sumptuous cheongsams, floral hues, and green checks fitting perfectly with the decadent decor of their small apartment block, almost too well. An act of camouflage, perhaps.

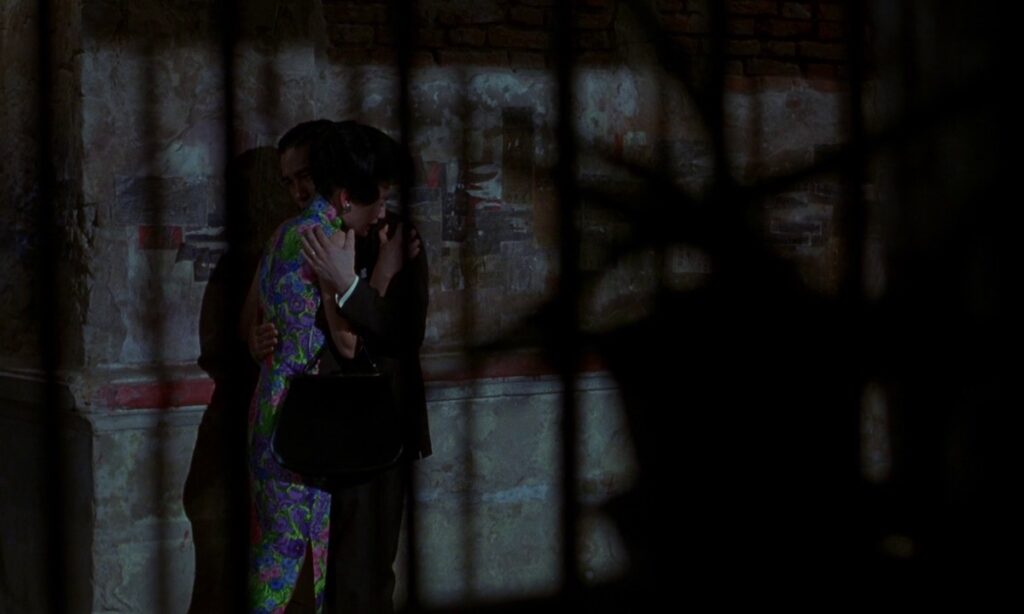

Their precision of clothing may almost be construed as a demonstration of the utmost conformity—of the upholding of beauty and culture, of appearances and tradition—in a tensely transitioning climate, both in Hong Kong’s political sphere as well as the microcosm of their domestic lives. It cushions itself nicely amid the almost unsettling habit the two have of imagining the courtship of their spouses, small gestures endowed with erotic charge, hands enfolding hands in taxicabs, backs pressed coquettishly against iron grills; rehearsing confrontations that never come to fruition. ‘Why did you call me at work today?’, ‘I wanted to hear your voice’; you almost think we’re being shown how they begin to fall in love, and then it is shattered with a ‘You’ve got my husband down to pat. He’s a smooth talker. Devastating. Adults playing dress-up.

Their own love story is much subtler, perhaps because so painfully conscious of the cliches they imagine their spouses, the encapsulations of everything they do not want to be to have used in the overture of their affair. Their story exists in the spaces between these cliches, in the brief snaps of sorrowful eye contact and brushes of rain-streaked hair. It exists in the absence of intimacy, the absence of desire being consummated. So much for Wong Kar-Wai is most fervently felt in what is not shown, what does not happen. In restraint. Perhaps regret.

In one scene, their loquacious landlady, Mrs. Suen, turns to her friends after Mrs. Chan has declined to dine with them once again, on her way to fill her thermos at the noodle cart down the road. ‘She dresses up like that to go out for noodles?’ she tuts disbelievingly, her hands sifting through mahjong tiles. Mrs. Suen’s comment, playfully said, nonetheless points to the lurking sense of watchfulness that pervades the film.

Mrs. Chan’s cheongsams, lustrous as they may seem, are incredibly slim-fitting, impossibly constraining, like the beautiful black heels she sways gracefully around in for the film’s entirety. It is when she veers from what almost becomes her uniform—albeit a lovely one—when she alters and detracts, that Mrs Chan is at her most free. Swathed in a daring red coat, she billows up the stairs to Mr. Chow’s new apartment in a fast-cutting montage, blending in this time rather dangerously with the trembling curtains, red as a lascivious shade of lipstick, or a provocatively beckoning fingernail. His apartment doused in the hazy purple light that gives it the quality of a Petra Collins photo shoot, spells risk and unfamiliarity, is almost bawdy in its decor. What happens there is remarkably chaste, however: the two of them pooling over his writing, trading ideas. The risk is shocking in its purity: two lonely strangers, united by an infidelity that is not theirs.

In a similar vein, when she finds herself in Mr. Chow’s room late at night, Mrs. Chan is compelled to spend the night when their neighbours return unexpectedly early, leaving them no time for her to exit his room without seeming suspicious. All that was going on within the confined space of the bedroom was that she was reading his manuscript; later, when ‘trapped’ there, they do not even share a bed. The next day, she slips out wearing his wife’s shoes, leaving her velvet house slippers behind so as not to attract unwanted attention or raise suspicion about the two of them. The slippers are a recurring article of clothing: they reappear later in Mr. Chow’s room when he moves to Singapore. Mrs. Chan leaves them secretly in his apartment, perhaps to remind him of their only night together, however innocently spent, and then, almost as an afterthought, ferrying them away again. ‘There’s nothing between us,’ she says, ‘but I don’t want gossip.’

The sensuality of the unfulfilled, the immensity of silent desire, and untapped physical intimacy, soars to a roaring pitch in moments like these. Wong Kar-Wai’s tour de force earns its rightful place among some of the twenty-first century’s greatest cinematic endeavours, enduring because of its beauty, its masterful simplicity, but above all, how it speaks to us universally. About what is said and not said. Done, and not done. Acted, and truly felt.