I find myself in the kitchen again, as always, my thoughts turn to you. How could they not? The way you rest so calmly, your soft flesh yearning for me to caress it below the warmth of tap water streaming down your shoulders, tracing every curve, drawing out your essence. I can almost hear your breath gack as I gently carry you over, to lower you into the simmering pot, your skin trembling just slightly as it begins to break down.

I feel your resistance, wanting to hold on just a little longer. Cluck cluck. But I know how to coax you, make you surrender, to ease under my touch. Once you give way, I’ll pick you up again, laying you down on the wooden board. I’ll take the knife, slicing through, slowly peeling back your layers, your skin will part as I continue to draw the blade over you– feeling your heat, the give of your flesh.

I’ll move deeper, using my fingers to slide along those soft lines of muscle and bone. Your bones– oh, your bones, love– are so cold, so fragile in my hands. I trace them, feeling their shape, their smoothness, their hollow strength.

Cluckety gack gack cluck.

*

I had hainanese chicken rice for dinner last night. It’s no surprise: chicken is the most consumed bird on earth, with around 23 billion of them clucking and gacking across the globe at any given time. And as the materiality of the earth shifts under the weight of exhaustive human activity to-be-fossilised chicken bones enter the planet’s strata by way of industrial-scale poultry farming– chicken meat, it’s cheap as hell. Cheaper than buying clay.

Cheap enough to have it as our permanent record, as in the geological record, the remnants of our time that archaeologists or aliens of the future will sift through to determine who we were and how we shaped our world. The chicken is suddenly this individual thing once more, a soul illuminated by teeth chomping down into it.

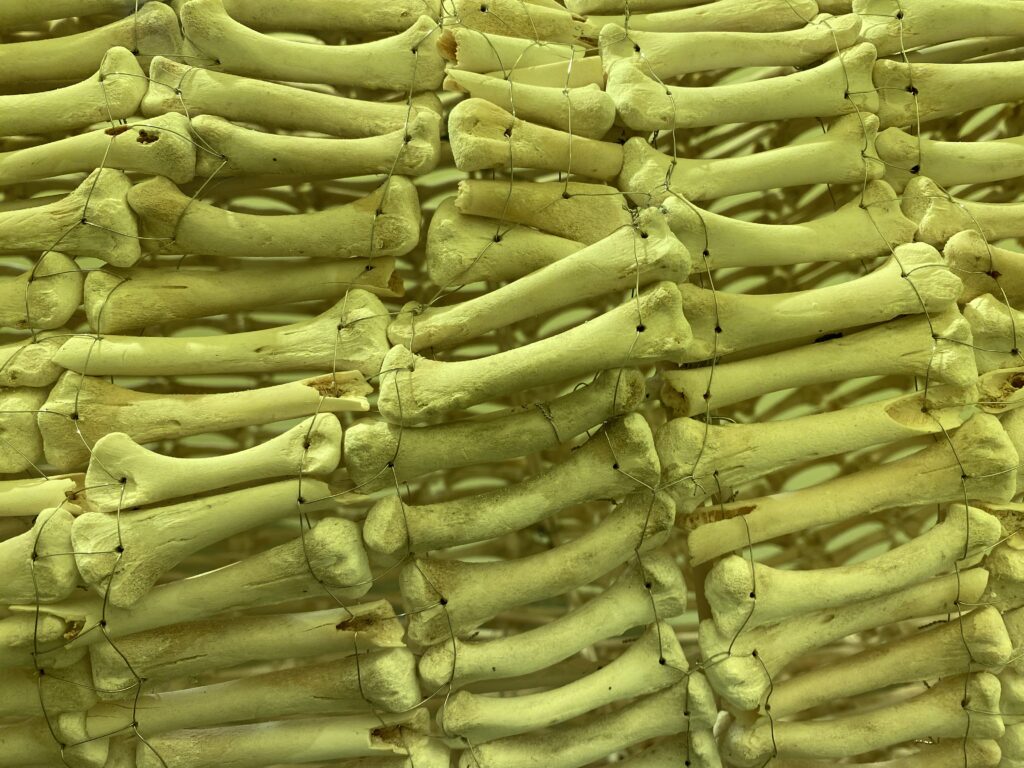

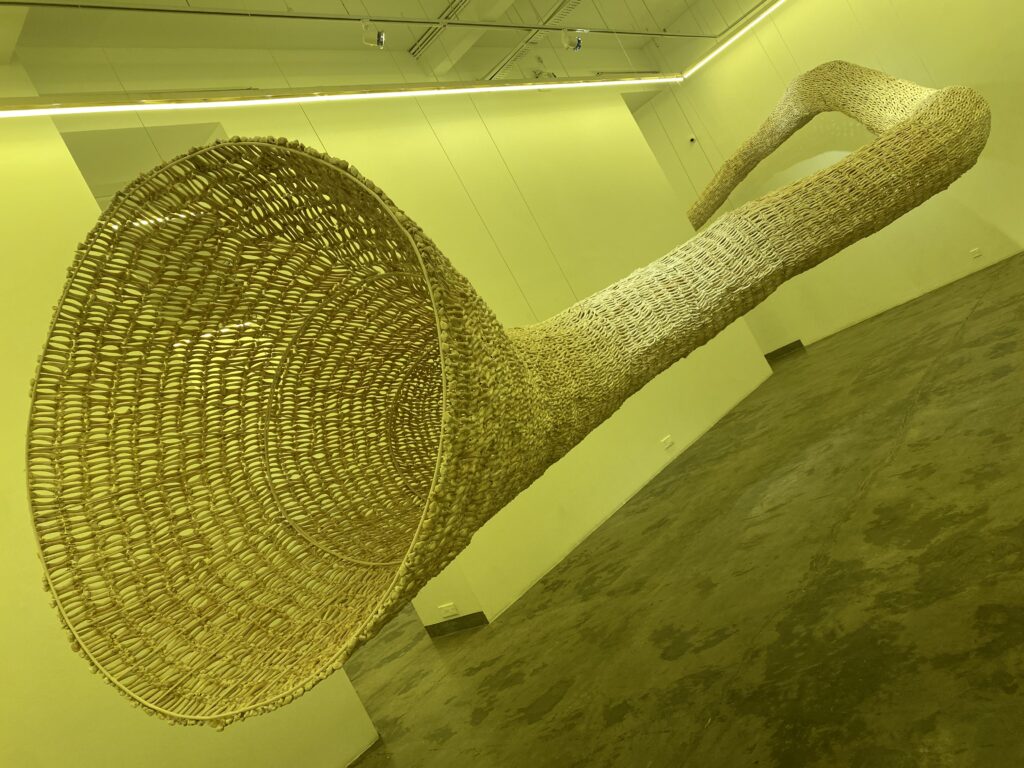

At A+ Gallery, Malaysian artist Adam Phong opens the door to a time warp. Bones hang suspended from the ceiling, coiled in wires. The lighting is tinged with yellow and I have to rub my eyes to make sure I’m not hallucinating the trumpet shaped sculpture drooping over me. Claustrophobic is my first thought. Fear my second. But mostly, there’s no time to think. Like my terminally online peers, I’d “prefer not to,” brain rotted from 24/7 capitalism, careening towards a meltdown. I am in fact, “mentally exhausted from dealing with the present, leaving (us) with no energy to imagine the future,” as the exhibition statement notes.

So I’m lucky that Phong’s exhibition– One of Our Fossils– curated by Bob Edrian, is naturally thought-provoking. Seven sculptures made of chicken bones are carefully presented to create a space for reflection, inviting us to imagine how future civilisations might interpret fragments of our existence. These bones are no longer just biological fragments but objects of history, charged with narratives, myths, and stories that reflect the intersections of culture and environment. The exhibition nudges us to feel out this absurd transcendence of time against our modern condition, reminding us of the fragile balance between permanence and impermanence. And, Phong is adamant about this: feeling things out…

When I try to photograph the larger sculpture alongside a smaller relic, the artist gently corrects me. He tells me to position myself in front of the piece as he’s intentionally left a gap between them, creating a space for telepathic connection—a ghostly transmission of meaning. Nothing is an oversight but an invitation for the viewer to envision what might lie between the two objects, to fill in the blanks. That’s when I fully understand, it’s all about imagination. We briefly discuss different could-be’s. “When archaeologists dig up old bones,” he says, “they’re just guessing at their meaning.”

I am reminded of an article I read a few weeks prior, about a research team who restored 14 of the 86 famous casts from Pompeii to extract DNA samples. In 79 AD, Mount Vesuvius experienced one of its most significant eruptions, burying the Roman city of Pompeii under a thick layer of small stones and ash known as laplli. As their bodies decayed, cavities formed that perfectly preserved their positions in their final moments. Since the 1800s, plaster has been filled in the voids and assumptions placed on the Roman Empire and its people. But with the advent of this new genetic analysis, findings completely contradicted previous beliefs. The study revealed that individuals previously assumed to be family– such as mother and her child, or two sisters– were not genetically related at all. This discovery challenges our assumptions about gender, kinship and social stereotypes. Also, it turns out the Pompeiians were far more cosmopolitan than previously thought, their DNA reflecting a mix of ancestry from across the eastern Mediterranean.

*

I make a joke: “chicken or the egg?” and Phong replies something about nature versus culture since the bones have been processed, cleaned and reassembled… He says something else about how “every bone has been touched by a mouth.” I try to continue this train of thought, to ask more questions, while I am still a little overwhelmed by the structures around me. “Do you know why chicken bones will outlast us?” He says that so much of fast-food involves chicken bones, when we eat it, the bones are wrapped back into the plastic they’re served in, before being thrown away and ending up in landfills– essentially they’re accidentally preserved.

He also tells me he was actually in Indonesia eating a lot of chicken himself, he was already collecting these bones before he read the scientific paper which inspired the exhibition. It was like he was preparing himself for an opportunity he did not know existed. And, I think the show reflects that. The experience feels organic. Phong was even careful to keep the project a secret from his parents and close friends because he wanted their experience to feel as such, organic and unmediated.

I still remember before walking into the exhibition, Phong turned around to ask me if I’d seen any of the works. I said no. When I entered my first reaction was to blurt out “Oh, wow!”

Phong’s work makes us reconsider how we leave traces of our existence in ways we may not even anticipate, like chicken bones ending up in our landfills and ultimately becoming a part of our future geological record. It’s ironic, what we consider waste can actually outlast us, leaving behind a record of our time for future generations to decipher. The artist plays with this idea of longevity, forcing us to revise the narratives we attach to objects and how those narratives are inherently shaped by our cultural and environmental contexts. So many of our assumptions remain in the present even if we (capitalistic societies) tend to obsess about the future and its progress. Our understanding can always be upended by new discoveries and tools. Phong’s work, much like the DNA analysis of Pompeii’s remains all these years later, challenges conventional wisdom and invites us to think about how we interpret the past with our present and future simultaneously.

One of Our Fossils is both personal and universal, connecting the fleeting nature of our current moment with the potential futures that lie ahead, in a haunting yet oddly comforting way. His immersive environment demands engagement. As he says, “science wants to discover, art wants to digest.”

One Of Our Fossils is on view till the 14th of December 2024 at A+ Gallery, Kuala Lumpur. Admission is free.