Accompanied by my most trusted equipment and confidante, driving past rush hour traffic, past headphone geared pedestrians, past construction crews, past the point of no return in the conversation of We Should Have Taken The Other Road, Is The GPS Glitching? and past 7, 8, 9 red cars on the drive to our destination. We reached the location and set on foot past a wide staircase, past a chaotic city, past trusting napping cabbies with feet outside of rolled down windows and arrived to the warm hello of one Badrul Hisham Ismail.

Up a pastel elevator and taking our shoes off at the door, the soft drizzle outside was no competition to the smell of coffee and serene surroundings of Badrul’s personal space. “I’ve lived here for six years now. Work with the other organisations I am a part of is done in the office but for my own work, even before the pandemic, I prefer to do all that at home”. Our interest in this personnel was piqued via the short films he has written and directed over the years, although the medium wasn’t always an obvious choice for Badrul. “At first I wasn’t thinking of doing any tertiary education because I wasn’t very good in school. I never had specific ambitions but I knew that I’ve always loved films. Like any regular Malaysian child when I was asked growing up what my ambitions were, I’d just say doctor though I think I should have said something easier. My whole former years of education was geared towards medical school which was, well, a disaster. I studied at a local college where I only lasted a semester before leaving. And then I was working, where I started to know a lot of activist groups so I started leaning into those kinds of works with NGOs. But even then I knew that I had to learn some type of skill. That was around the first time I heard of somebody actually studying film. Before that it never crossed my mind that it was something people studied how to make. I decided on a one-year filmmaking course at the New York Film Academy. You didn’t need prior experience or a portfolio. It was really just people who wanted to come and try to learn, so I did that.” After studying and working in production in the States, Badrul felt himself to be an unuseful participant in other peoples’ productions. “It’s a lot of craft work and you have to really understand what each individual person wants in their work. I don’t think I was very useful there and then. I decided to try and make my own small films before deciding to do my degree where I had a scholarship to pursue liberal arts at The New School.” Badrul’s tertiary background boasts all of this and a Master’s in urban policy from a university in Singapore. He is relaxed in a snug armchair across from me as he casually regards, “In my head, all these subjects I’ve learnt are connected to each other.”

Born in the United Kingdom to a father from Terengganu and mother from Bandung, then moving in and around Malaysia in his early years, having a diasporic history is a foundational fundamental for Badrul who embodies these questions of personal politics in his multifaceted works. “Including me there’s 5 siblings and I’m number five. None of my siblings were born in Semenanjung Malaysia and they all have a very worldly attitude in their approach in things. I grew up in Kajang but I experienced it through the kind of movies we would watch and books that we read. We’re now all in very different fields but whenever I want to do any weird things, I’d always have their support by letting me do what I need to do and not have to conform in any way. My mother was a mak andam and she did tailoring jobs but no one in my family actually saw that as creative or art work and was viewed as more of a side job. Nobody in my family came from an art or creative background and it wasn’t in our thinking to work in the creative industry or to produce our own work. Even so, literature was something that was always appreciated in the household. My parents used to send my siblings and I to small state libraries where we’d spend our time. Because of that, we were all really into story-telling and building on fiction but never to make a career out of it. When I reached the age of really thinking about my own ways, I knew that I should study film which had less to do with whether I thought I could do it and more to do with the fact that I liked films enough to know that I wouldn’t hate learning more about it.”

Upon returning to Malaysia, Badrul joined efforts with IMAN Research during its budding stages. “It’s a small organisation, there’s five of us so it’s flexible in that sense. We do a lot of research with interest in political climates”. Also the co-founder and content editor of print journal Svara, Badrul notes “Svara actually has to do with Zhongshan building. Nazir, who runs Tintabudi, opened up in Zhongshan. I hung out there quite a lot where we often had conversations about literature and publications. I actually published another short zine that only lasted one issue with another friend of mine. After that, Nazir and I discussed a collaboration on a publication that could be something more than a one-off edition. At that time, he was already talking to Hafiz Hamzah who has been his own publisher with Obscura. When the idea for the three of us to start something together came around, I thought, why not?”. With film, Badrul tells us that this is a venture he does independently. “I’ve been making my own short films for a while. I know that’s something that’s not easy to do full-time because the kind of things that I want to do are not really market-friendly. So I knew that I would need to be doing other things for revenues and then whenever I have a chance, I do these little projects here and there. Which is how I’ve been operating with filmmaking for the past, close to 10 years”.

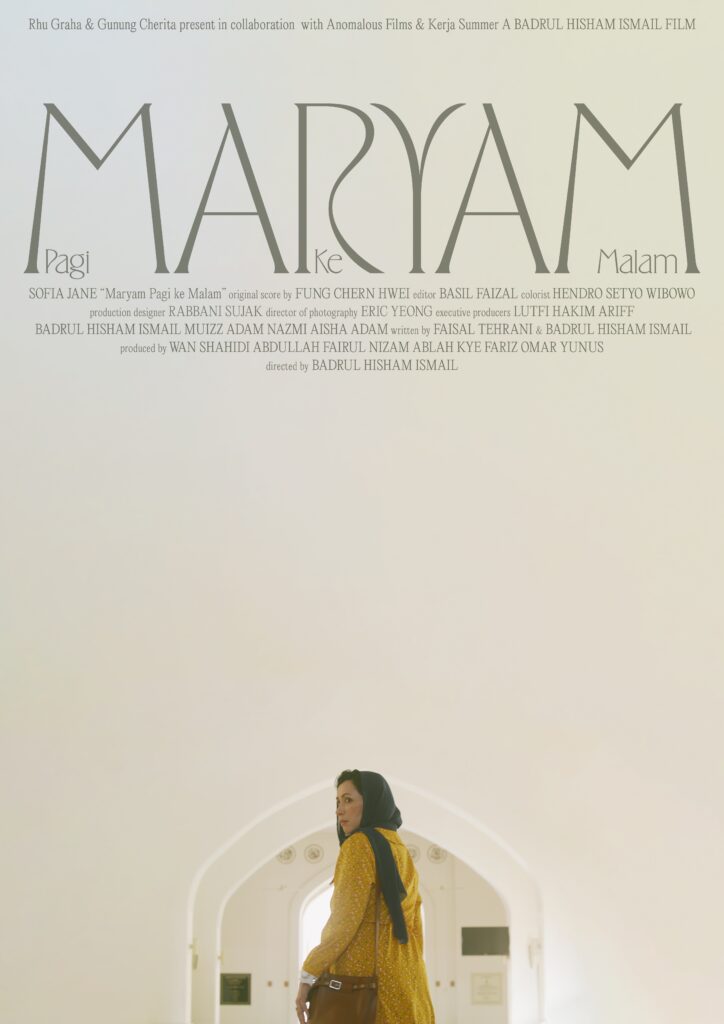

Through the years, Badrul’s filmography has consisted of short films ‘A Tale of a Mannequin’, ‘Apa Khabar Adiguru?’, a feature documentary ‘Voyage to Terengganu’ and most recently, his first feature film, ‘Maryam Pagi Ke Malam’ that had its international debut at International Film Festival Rotterdam 2023. Maryam is the story of a 50-year old gallery owner from an aristocratic family seeking blessings from her father to marry her much younger boyfriend from Sierra Leone. At the same time, she needs to overcome the challenges from Sharia bureaucracy which determines her ability to choose her own spouse. When men write womens’ stories, there are lines that lie between an empathetic allyship or fetishised fantasy. In the case of Maryam, Badrul Hisham Ismail and Faisal Tehrani shows that it is the former conclusion that displays itself throughout this motion picture. “When I first wanted to write the story, what I wanted to write about was bureaucracy and institutions. I never really liked them in general, in any country. I wanted to write something regarding that structure in a Malaysian context. When I thought further into it, the ones who have to deal with these oppressive institutions are women more than men as men tend to get away with more things. There is a clear double standard in all that. And if I was going to write about it, it has to be from the perspective of a female protagonist because they are the ones going through it and the disparity is really obvious. I went through a few directions in terms of how I wanted to tell this story but I decided to talk to Faisal about it first. We’ve always wanted to collaborate at some point and he has knowledge regarding these issues because of his academic works and writing as well. We ended up writing the film together. I only had the name of the character which was Maryam and a plot where she was dealing with her fathers’ rejection. Faisal took those pointers and explored actual cases through friends who were lawyers in Sharia court. All of this was happening during the lockdown so we were both doing research and exchanging information until slowly we came up with the script, both the character and the legal issues that a person can have when dealing with this kind of case”.

Maryam is further embellished with a team of promising casts and crew. The cinematography, placement of every object, locations, Maryam’s beautiful yellow dress, how everything looked, how everything felt and of course, yes, please, its soundtrack was an unforgettable illustrative experience of depth in independent creativity. Sofia Jane’s performance as the leading lady concludes that no one else could have breathed life into Maryam with more instinctive intentions and ease as she did. “When we cast Sofia Jane as the lead, a lot more things started falling into place. The dialogue didn’t change from the script but that was when we could really solidify the character’s backstory. Faisal and I had already thought that whoever plays the lead, that person would have to fill up whatever it is that we’re missing. There are a lot of things that we wouldn’t be able to know off hand regarding the character since both of us are men and we’ve never gone through the character’s struggles at a personal level. When Sofia came in, she really did all of that”.

Having spent a little over a year on the preparations of the film, every detail was continuously revised until the version we see on the silver screen was born. This careful curation is evident and educational to audiences who don’t necessarily have prior understanding towards how the theme of this film is closer to a non-fiction documentation than we think. With plans to host screenings of Maryam in and around Malaysia, Badrul tells us “My team and I want to screen it here but the budget and scale of the production is still considered to be small so it isn’t easy to do it through multiplexes. Also there is the process of censorship and reduction that we don’t want to go through. When Faisal and I were writing the film, we knew beforehand that we had to write it without the thought of censorship in mind and to just focus on writing whatever we wanted. We aren’t burdened to have it screened in cinemas as it wasn’t part of the plan or any agreement. So I thought, why not just use this position to make something that we don’t need to overthink. Of course we still want to have it shared in Malaysia and I’m in discussion with a few people in terms of how we can navigate the regulations here so that we can host screenings. Most likely, it would be done through private screenings”.

Platforming Maryam as a film that touches on the variety of subjects, Badrul Hisham shows a steady maturing in his approaches amidst this societal debacle. “Five years ago I wouldn’t even have made this film. It would’ve been a different film altogether. In terms of the story, it’s just an accumulation of how I’ve observed Malaysia through all my years that has lead to the worldview that I put in this story, the characters. In terms of the film itself, since it is still my first feature length fiction, it was more of a learning process for me. Prior to this, I’ve only worked with myself and 2 or 3 other people and never with a whole crew. I remember a friend that I had previously worked on a short documentary with who is one of the executive producers for Maryam telling me that next time we shoot, we’re going to need a screen for us to see our shots instead of looking through the camera. And on the first day of shoot for Maryam, he came down and I had a screen for myself, the assistant director had a screen. I was thinking of only getting one screen but now everybody has a screen!” He remarks with an echoed laugh. The image of this set through his story, painted in our heads. “It was a really great learning process for me to learn how to work with a big enough crew, it’s still a relatively small scale but a lot bigger than anything I’ve done before. It was truly a collaboration with others rather than me trying to do everything. Initially, working with other people was a concern for me but I was lucky to get an opportunity to work with a group of people who were not only experienced, skilled but also really into this story as well. No ego, no nothing. Everyone was just trying their best for this film. I think I’ve learnt so much more from them than they did from me.”

With experiences in the industries’ many faces both locally and abroad, Badrul shares the importance of communities in bringing creative vision to life. “For the most part, it’s just saying yes to people who have interesting ideas. Other than my own film works, everything else that I’m a part of are other peoples’ ideas and they ask me to be a part of them and I just say yes. Most of these are things that I’ve never done before. Managing expectations is an important factor, to have an idea of your own desired outcome from your participation in any project. It’s really about knowing what you can and cannot bring to the table and not overthinking about how this is going to help your career. I don’t have this kind of thinking to begin with, I mean if you ask me about my plans or career trajectory I have no idea and I’ll just focus on whatever that is in front of me. When people who have interesting ideas, want to do interesting things and for some reason are open to me helping or collaborating with them I just say yes.”