Is an artist someone who simply puts pencil to paper, brush to canvas, and allows the process to consume their artistic substance? Is an artist someone who bridges the gap between creative freedom and financial need – one who constantly toes the line of who they are and what is expected of them within the webs of patron-client linkages? Is it a state of being, a spirit of the mind, a way of life?

Or can an artist simply be an artist by claiming the title, given that the term itself eludes any form of cohesive understanding? It is a word that, when spoken aloud, bubbles up into the air beyond our reach. For multitalented Tan Zi Hao, there seems to be a negation of this title, emphasising that he is, above all, a human being sharing the collective burdens and responsibilities of humanity:

‘There is no need to define myself as an artist. I educate, I write, I make art, through which there is something I want to say, which I also hope will leave an impact on society. For me, it is quite clear from the get-go that my practice cannot be bound to a single discipline. For instance, art-making is capable of the most radical vision but it may not affect an immediate transformation due to its discursive nature and the attendant privilege.’

Education, on the other hand, is more immediate and potentially transformative but is always hampered by expectations that demand specific utilitarian or economic outcomes. Working across different disciplines is also a contingent strategy that I find increasingly necessary in an environment of neoliberal corporatism with imperfect infrastructures.’

One is always subsumed by captivation when engaging with a Tan Zi Hao piece. His work is conceptual yet reachable, mystical yet down-to-earth, finding resonance within the frequencies that define public life. It is outstanding, subversive, powerful, perplexing. And if anything, it is political. When I asked him about the political undertones of his work, TZH spoke of his coming of age as an artist during the heat of the 2008 General Elections. Noting that it was the first time Barisan Nasional lost its two-thirds parliamentary majority, Malaysia (at the time) was experiencing its first ‘political tsunami’ where waves of change seemed to take over the hearts and minds of educators and artists alike.

The unfathomable fall of Malaysia’s political goliath provided a spark of hope for reform and new idealisms, envisioned within the works of contemporary art which sought to reimagine what a new Malaysia would look like, and what it could be. This euphoria of change has since followed TZH throughout the years and his critical yet insightful outlook on the politics of resistance, race, and political patronage is both refreshing and necessary. His works Bhāṣā Jīva Vaṃsa (2017), Tin Kosong (2020-2022), and One of You Has Expired (2023) tackle themes of linguistic origin, political leapfrogging, and electoral apathy that act as visual symbols of our times. What is particularly interesting, however, is his fascination with the question of multilingualism, which for TZH (whose mother tongue is Mandarin) strikes a particularly significant chord.

When asked about his thoughts on the challenges he has faced in articulating a complex multilingual community that evidently subsists in Malaysia, the realities of power asymmetries and postcolonial legacies become all too apparent:

‘What is immediately apparent is that multilingualism is almost always a condition of the minorities, of the less powerful. Multilingual translation is a necessity for marginal cultures but a luxury for the dominant culture. English is the language into which others translate in the global arena; Malay is the language into which others translate in Malaysia. Most of my works on language politics reflect how multilingualism is a contested ideological battlefield, rather than a symbol of cosmopolitanism and cultural diversity. The latter idea is inherited from colonial epistemology (the desire to govern and be inclusive). These varying contextual factors create very different entry points and challenges for reading my works. For example, an Anglophone living in an Anglophone environment will struggle to resonate with my problematique because language is not a matter of topical concern in everyday life. I think to be able to perceive language as a problem requires an experience or a memory of displacement, which are mostly (but not exclusively) tied to communities with a history of migration.’

‘Colonialism did provide a certain condition for its politicisation, but the result is not always as intended. Language is heavily political in Malaysia (more accurately, in West Malaysia) because it was a bargaining chip dating back to Tunku Abdul Rahman’s time (i.e. his infamous Language Bill) and it was, unfortunately, yet understandably, tied to ethnic identities. From the 1960s onwards, we witnessed the rise of what Tunku Abdul Rahman would describe as the “ultra-Malays” and “Chinese chauvinists,” both arguing for different language policies. I do not agree with these dismissive labels, for they were in fact language and education activists, with vastly different understandings of what constitutes a “nation.” Nonetheless, we still live in the shadow of that conflictual history. If we could learn to see beyond the conflict, perhaps, the two are not that distinct in their collective zeal for upholding a language. Can language ever be cleansed of politics? If we consider “politics” as an integral part of life, language (or everything else) is always already political. To speak of “politicisation” presumes that there exists an apolitical, or pre-political, dimension in human life?’

However, when further pressed on the postcolonial context which Malaysia grapples with, TZH makes clear that a line should be drawn between the critical observation of our past and an overemphasis of nostalgia that tends to imbue institutional and epistemological inertia:

‘I am very cautious of the risk of romanticising my subjective experiences and am suspicious of nostalgia. I believe it is crucial that we understand our history and heritage, but any attempt at celebration is often selective. I have no qualms about sanitising traditions or modernising past heritage for a contemporary audience, but what and why certain components are selectively removed are seldom revealed to the public.’

In expressing these themes, the observer cannot help but engage with these works as historical artefacts, placing emphasis on historicizing our imagined futures to uncover the structures of power and privilege that they preserve.

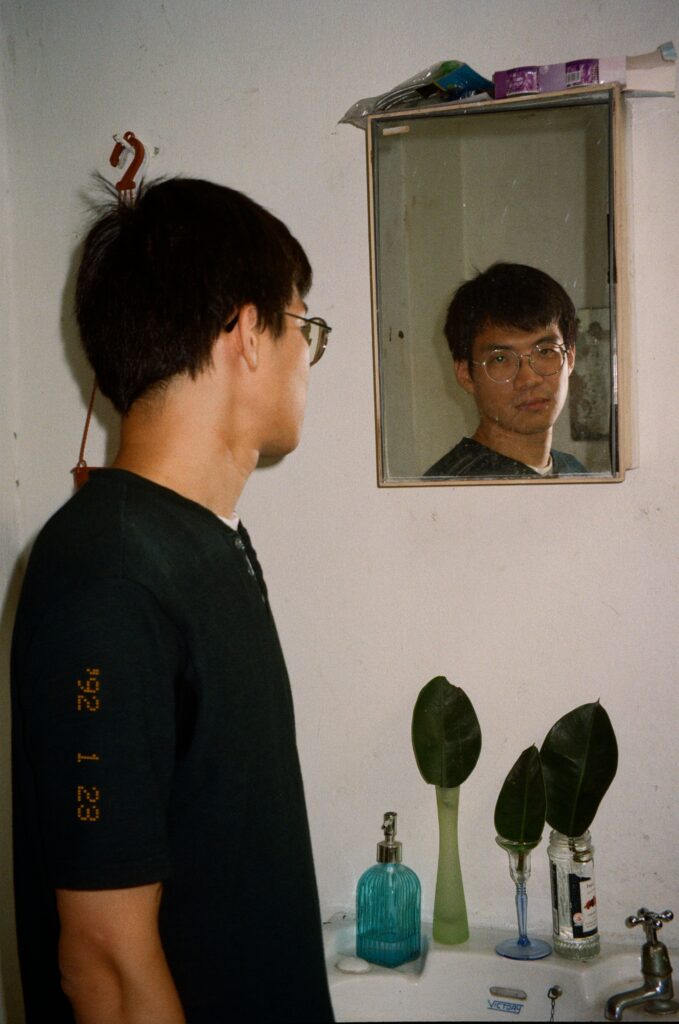

But what lies beyond these works? Who is the man responsible for them? I met TZH on a sunny afternoon at his shared workspace at 293 in Petaling Jaya, pleasantly surprised to find an individual, who was both smart and had great bone structure (one that is like an eloquently put novel) awaiting my arrival. We sat and talked about his journey in education and art, the shaky state of Malaysian politics, the assimilation of Islamic art in Southeast Asia, and his upcoming projects—our conversation taking on the fluidity of the quiet breeze that intermittently blew outside. I found out that his upbringing in Serdang, a predominantly Chinese locality, has played a significant role in inspiring the intentions and ideas that garner his work, providing a personal take on the intricate maladies that stick upon the conundrum of ‘Malaysian-ness,’’ tied alongside its nation-building efforts. However, he is careful to tell his audience that the reflection of his identity should not be construed as the prime motivator of his work:

‘It is not always conscious to me when my works reflect my identity as a Malaysian-Chinese or if it addresses my diasporic sense of belonging. Art-making, to me, can be intuitive or consists of a period of prolonged research and analysis. There are certain experiences that I may find captivating and perhaps what drew me to those moments has to do with my social and cultural upbringing. I could not escape my history, my place—my sense of belonging—but likewise, I could not elaborate on how I explore or redefine them. What is certain is that I view my subjectivity with a critical distance and am extremely cautious of the risk of romanticising it. Even though my experience can be subjective and singular, I believe they point to a common condition of being human, with regards to home, mobility, and belonging.’

In conversing, I came to find out that the artist is highly learned in multiple fields. From earning himself a diploma in graphic design and advertising to a PhD in Southeast Asian studies from the prestigious National University of Singapore. This insight, to me, explained the conceptual richness of his portfolio. I found out that he is a man of practicality, only using materials that are readily available to him in the process of creating. I also found out that he is rather awkward in front of a film camera. I guess one has to give and take with some things.

But I think what stood out most in our interaction was his emphasis on the role that art plays within the public sphere. He makes it clear that public expression through the medium of art should have the intention of challenging certain issues, providing a visual ground for valued discourse to happen. That, to make art, is to push forth a personal idealism; to be able to take part in a collective dream and take the first step to make it happen. As he says,

‘I believe an artist shoulders the responsibility to produce works that ask critical questions about the society we live in. I actively engage in this so it becomes necessary to articulate myself beyond art-making. The question of modes of expression – or mediums in general – is always secondary and dependent on the roles I assume in the fields of art and pedagogy.’

On the other hand, art is there to also capture events of collective despair, to provide a basis for reflection, an attempt to scream out ‘Never Again!’ as we hold on to each other in breach of our trajectories. Despite the unavoidable limitations that art holds in public consumption and reflection, it is this attempt that counts, it is in this attempt – and not necessarily the solution – that the grandeur of life holds itself. ‘The power of art is to show a certain ideal vision which is not necessarily practical and with no expectation to be utilitarian.’ Art in this context is simply there awaiting to be looked upon, to be laughed at, to be stared down, to be criticised, to be frowned upon – leaving an indelible mark on the conscience of its observers as they traverse back into the dizzying rhythms of the everyday.

So I ask again, how do you define an artist? What methodologies can we trust, and what truths are to be told? Deeper and deeper I fall back into this problem and the more I think the more I realise that the fault lies in the question itself, for to define the ‘artist’ one has to define ‘art’, and to define ‘art’ is a futile mission. For is it not that the powers of art are ingrained within ourselves, that the only difference between us and those ‘artists’ is the will to act upon our dreams, to invigorate our souls, to nourish our minds, and to be brave enough to stare directly into the eyes of hard truths.

The concept of the artist is everywhere and nowhere at the same time. It lies within the singular and the collective, weaving the individual in and out of the fabric of national wisdoms and ideals. It lies between the historic and the nostalgic, within the need to justify and the need to inform. It toes the borders of expression and romanticization, the real and the unreal. It is multifaceted, and because it is multifaceted it is not a concept that one needs to define. But instead, to feel.

*

Creative Direction by Alia Soraya

Photographs by Pravin Nair