Paired with the illustration of a man in a beret and a handlebar mustache, the artist was voted as the number one non-essential role. Not only is ‘artist’ an umbrella term that describes individuals who partake in any form of creative pursuits, but the label also serves as a compliment for anyone who excels in their own field. Compared to other more specifically defined roles (e.g. doctors and cleaners), the audience presumably relies on snap judgment to form an archetype of the artist. This idea is not dissimilar to the aforementioned illustration—a frivolous creator in pursuit of aesthetics with little care for utility, often successful with a privilege towards rejecting capitalism. They had forgotten about the other artists whose contributions they engage with on a daily basis: photographers, illustrators, models, actors, and musicians.

“Illness is the night side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place,” writes Susan Sontag. In hopes of keeping our good passports, the pandemic has pared us back towards utilitarian-based ideas while simultaneously driving the allure towards partaking in various flights of fancy as a form of escapism. Harkening back to the First Law of Thermodynamics, art exists simply as a reaction towards the living experience—as energy is not created nor destroyed, art merely represents a transference of vibrational energy onto the artists’ respective mediums. Although execution may not always be literal, the amalgamation of influences from the artist and society at large are present and direct. The historical value of art lies in its reflective, documentative nature that is vital for posterity. “Oh happy people of the future, who have not known these miseries and perchance will class our testimony with these fables,” wrote poet Francesco Petrach to his brother who was a sole survivor of the 12th-century bubonic plague.

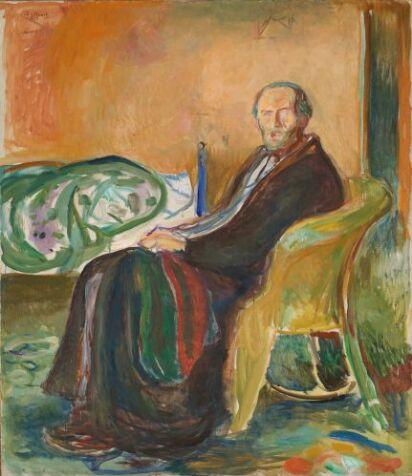

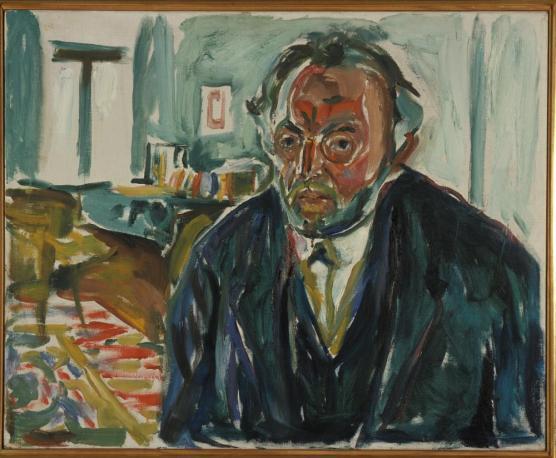

Unlike conventional sickness, a pandemic incites collective isolation that requires us to be alone together. “The Spanish flu is remembered personally, not collectively. Not as a historical disaster, but as millions of discrete, private tragedies,” writes journalist Laura Spinney. The most recent pandemic before the coronavirus, the Spanish Flu that ravaged about 50-100 million lives a century ago offers glimmers of insight for us to draw parallels from our lived experiences. As a form of solace from unseen terrors like oppression or viruses, creative minds would often turn towards their imagination to metaphorise their reality, Megan O’Grady of the New York Times suggests. However, the imagery of this pandemic paled in comparison to the other global crises that were happening concurrently (the Spanish Flu took place 10 months before World War I ended). As most artists from that time period focused on war-related imagery, notable pieces of pandemic-themed art like the self-portraits of Edvard Munch have given visual insight into the lives of people then. In line with Munch’s usual themes of melodrama, existentialism, and suffering, he depicted himself as a tired, dishevelled-looking man with his mouth ajar. A symptom of the flu? Difficulty breathing.

However, unlike his previous works that revolved around death and those who surround it, Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu pictured him alone and further emphasised isolation as a common denominator during pandemics. During the AIDS epidemic in the 80s, the concept of metaphorical thinking was not without its critics. While understanding the inevitability of metaphors, Susan Sontag cites the dangers of igniting mass hysteria and suffering among those affected through instances where people would regard AIDS as a plague, signifying the disease as a form of punishment given its association with nightlife and queer identities.

Although with initial plans to relaunch early this year, the Malaysian National Culture Policy––which has remained untouched since its first iteration drafted in 1971 ––has predisposed the local Arts and Culture Sector to a myriad of challenges without a properly implemented support system. This pandemic has only exacerbated the impact. With a niche market that’s saturated with talent but lacks consistent demand, galleries are proactively looking at virtual platforms and alternative forms of exhibiting to engage with their audience. A recent example, Gerak Angin was part of the first Malaysia Virtual Arts Festival (a joint collaboration between Masakini Theatre, Sutra Foundation, and Surprise Ventures along with support from the local Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture), was successful in providing the masses with access to performances. Art fairs and exhibitions that require a physical presence like KUL Biennale 2020 and Art Expo Malaysia were postponed with hopeful organizers looking to reinvigorate execution and engagement strategies next year during their return. Museums that once served as a popular spot for foreign tourists like the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia are now hoping to attract local visitors looking for a less crowded art-viewing experience.

While cultural institutions and collectives may possess more liquidity to stay afloat, the community of artists who have heavily relied on the gig economy without the backing of a constant income has been feeling the brunt of this pandemic the hardest. The decision to pursue what they enjoy and are good at comes down to the privilege and financial stability they possess. As a response, the Cultural Economy Development Agency (CENDANA) has also taken long-term initiatives to support the 10,000-something creatives by raising public awareness, urging policymakers on top of offering immediate response grants to artists in order to sustain the local arts industry. Other than a general trend towards diversifying their skills, writer Ellen Lee notices a shift towards community-focused, commission-based opportunities to allow mutual aid and better allocation of resources. As local designers sew away PPE gear to support the frontline, Fahmi Reza offered custom portraits to donors who participated in any of the #KitaJagaKita movements. The general public also had a chance to share Red Hong Yi’s platform which was used to showcase what people are yearning for the most in a project aptly titled “When This Is Over I Will”.

Despite its conventionally elitist perception, the patronage of art is universal and assumes a multitude of forms. Similar to how Dadaism and Bauhaus emerged as responses to a war-ridden society in search of absurdism in the midst of chaos and design that’s purposeful and hygienic respectively, new forms of resilience will emerge as a result of collective trauma. Art is necessary and will remain till the end of time, but we will need more purposeful ways to support creators through effective policymaking and education that empowers talent building and sustainable models of monetisation.

Some say nosy, he says curious. Through writing, LingJie observes his surroundings with an insatiable kaypoh mindset to unravel the know-why’s and know-hows of subject matters that pique his interest. With a primary interest in fashion, arts, and popular culture, his early years spent with Internet access and excess have helped fuel his fascination towards what’s beneath the glossy, printed images that are ready for consumption—craftsmanship, creative processes, cultural infatuation, and the person behind the celebrity. When he’s not thinking about writing or feeling giddy when he gets to write about himself from a third person’s view, he can be found saving reaction images and memes off Twitter. Find him on his website and Instagram.