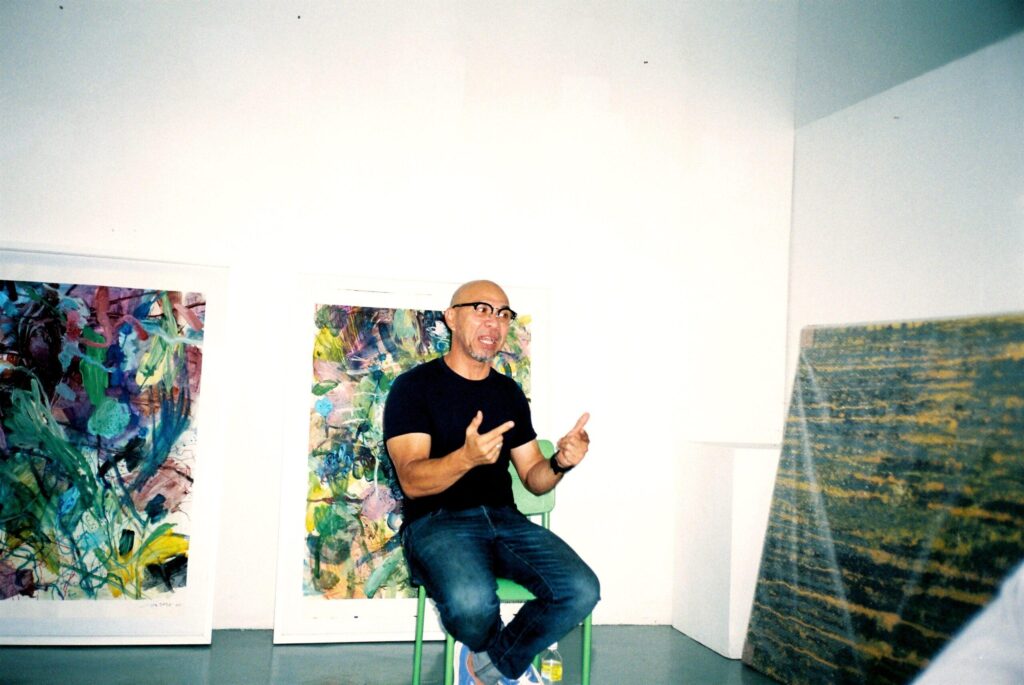

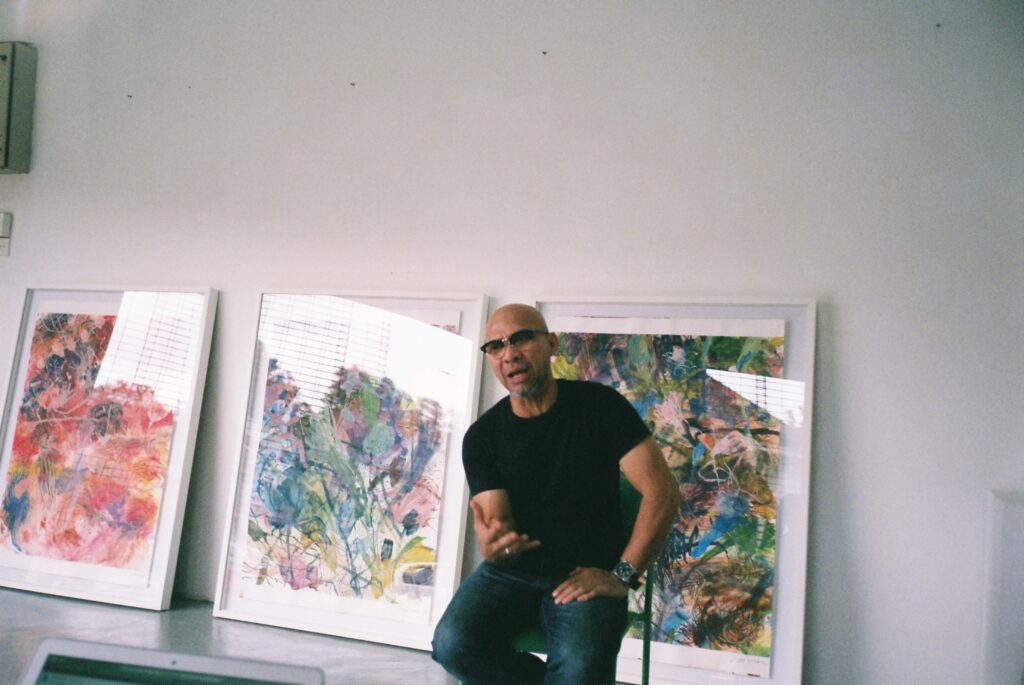

We see that it tells a story that goes beyond the empirical borders of its canvas and reveals the inner workings of its artist – in particular, the journeys and processes that underlie their work. This understanding found resonance during our little santai with the down-to-earth Prof Madya Jalaini Abu Hassan, as we discuss his navigations through the themes of the sense of self, Islamisation, and the embracing of blunders as undetachable characteristics to who we are. An alumnus of the prestigious Slade Institute of University College London and the Pratt Institute of New York, he explains the pivotal moments and periods that are still continuing to rebuild the walls of the art industry today; a gradual discovery of artists and identity happening simultaneously. Located at his open and welcoming studio Jalak, we were more than delighted to have the opportunity to have a little chat about how one can grasp the fluidity that defines the workings of art, and why at the end of the day it is important to stay true to yourself in your expressions.

How would you define your profession? Are you more of a teacher than an artist, more an artist than a teacher, or both?

I find that it’s a difficult question to give a simple response to because we have to consider how integral both those fields are. You need to be a good teacher to be a good artist, and a good artist to be a good teacher. You can’t separate them. I believe that art is something practical, and it causes you to be overly self-conscious about your skills, as you need to practice and harness your skills in order to teach. They want to see how you do your art, not necessarily the thought process behind them. So you have to have that sense of being able to show your art skills to produce a physical piece, in order for your students to see, and that is the teacher part in you. And to be able to make a good drawing is necessitated by an artist, to prove that you’re good at what you’re doing. So that’s why I feel like I am wearing two hats at a time- sometimes I’m an artist, and other times I’m a teacher. Whatever I produce in my studio, I bring back and show my students, and whatever my students produce, I try to bring them back to my studio. I feel like I am regularly inspired by them, and we regularly discuss art. It’s a back-and-forth thing. And I feel that is what distinguishes me from other artists, the collaboration between being a teacher and an artist simultaneously, which I see as being an advantage.

How much have your students inspired and influenced your art?

I wouldn’t call it inspiring per se, more like giving a source of energy to do what I do. When you talk about matters in the studio, and now you can’t wait to get back to the studio, and when you’re in the studio, once you discover something, you can’t wait to share it with the kids. So that is how we inspire each other. In terms of influence, it’s normal for art students to look up to their teachers like I had done before. And I find that healthy – that before you find your own way, you look up to certain individuals who have widely influenced you. So, as a teacher, I try to become their role model. But there are certain caveats to that. At times they get so inspired by you that they start copying and plagiarizing your work. There was even a time I told them

“If I see any more bitumen in your works (a material widely used by Prof Jai), I am going to fail you!”

It becomes a problem when they follow your footsteps too closely until they can’t let go. So you have to monitor that and impose controls when you need to. Of course, there are times when you feel flattered to have influenced them to such a degree, but at the same time, there are dangers to that, eradicating your student’s self-identity.

In your experience as a teacher, do you feel that there is a lot of potential that lies within our art industry in the future?

Recently, yes. I feel like we have picked up a lot in the last 10 years. And of course, the new generation of artists are looking at art differently. There is a new level of assessment behind their work. Cross-disciplinary and trans-disciplinary methods are languages that these artists are making use of. And I feel that art is a great medium for it. Everything now involves art, as compared to then when art was so exclusive- it belonged to certain groups and classes within society. But it doesn’t seem so right now. I feel that my daughter is now on her phone every day, and that provides her access to the arts. One time she asked me for a ukulele, which I found quite an odd request as she doesn’t play any music. But I bought it anyway, and she locked herself up in her room for two days. And I was shocked to see her play a Beatles song the next day, all thanks to an app. She only needs only to go on YouTube and search for a ukulele tutorial and in a matter of minutes, you’re able to keep up with them. Within two days, she became a musician. It shows you how art and ordinary lives are gradually merging. And I feel like my students share the same attitude, and it has changed the arts tremendously. I find that very advantageous.

Going back to how technological developments have progressed art to become much more inclusive, we still believe that particular forms of art: visual art, sculptural art, and the act of going to exhibitions, in essence, are exclusive avenues reserved for a certain populace. Do you find this true? If so, how do you think we can make these particular forms of art more inclusive?

I think it all boils down to our history with art. Art is something relatively new to us. We started in the 40s, much later compared to our neighbours in the Philippines and Indonesia, who started hundreds of years ago. Their knowledge of art and sensitivity has been greatly embedded within their culture. In Malaysia, we only started when artists like Abdullah Halip and Yeoh Man Sing started to make watercolour pieces for the British. So we have a young history in terms of appreciating art, which I believe has led us to this misconception that art is exclusive to certain groups, and that art is only for the talented few, and that is art is this pretentious, “syok sendiri”, thing, and they start to compare it with other disciplines. That misconception has moulded us into where we are now. That is not welcoming or “terbuka”, and I think that my generation suffered that severely. But not this generation. New forms of expression like street art, mural art, performing arts, and even community-based art are very largely applied today. So, going back to your question, I believe that we are opening up to the mass public, and we are opening the concept of consuming art in a broader manner.

And having said that, being in Jalak, I remembered when I proposed the idea of this space to the owner of the building, saying that I wanted to have a centre for the community to explore art. I wanted to provide free art classes and small workshops to teach everyone and the owner loved the idea. They told me how art and the studio [Jalak] can act as a medium to engage with the community, compared to the grand galleries that people find to be too exclusive. So, the community has become part and parcel of the component that needs to be addressed in order to make art more reachable and accessible.

We see that many more galleries and art institutions are becoming more community-centric in terms of involving more people in their activities and operations.

Yes, and I very much agree with that in believing we are heading in the right direction. And we also see more actors and intermediaries like MulaZine who are engaged with the community and the art industry. But we also need to recognise that there is another side of art: the market, the buying, the selling, and art as a commodity, which is another section altogether.

We’d like to move on to how you see yourself as an artist. I remember when I was younger, I attended one of your workshops at RumahLukis, and I recalled how you told us to not be afraid of making mistakes because mistakes are part of the art-making process.

Yes, I always say “if you make a mistake, make a big one.”

Right, so do you believe that artists today are very strict on having a context or a sub-context before proceeding to make their art and therefore following a stringent procedure when they paint, or is art much more fluid to them?

I feel that art is much more fluid. As I said earlier, this new generation of artists is adapting a new vision of what art is and what it can be, and it has become much more organic because of it. I feel that is what university and academia are all about. When you go to “learn” about art, it is not so much about learning to make a piece but learning how to engage yourself with the processes of art-making. We are not always interested in the product, but more on how you get there. I was recently with a student just now and their whole thesis is not about their artwork, but rather the journey they took to reach there. The process is what makes up the entire thing.

But there is nothing new with the “process” actually. In the ’60s, a group of artists established as the Process Artists, where the birth of performing arts took place. This was where artists would perform their processes of art-making and end it then and there. However, only now do we see “process” as an academic term. People now are interested to see your mistakes, how you’ve tried and erred. So, when you talk about young artists, as a teacher I encourage these things. Your product might not be superb, but the process of getting there is the whole journey.

I had a student who had a show recently, and instead of showing his work, he showed them all the different processes that he had honed. When the people in charge enquired him on his final product, he answered:

“Oh, you mean the result? I am not giving you the result, but the process towards it”.

And I found that to be a very good answer. It’s important to remember that the process is the whole phenomenon of creating and what you’re getting is just the by-product of it. Getting there is an amazing experience – your failures, uncertainties, and accidents ultimately are the joys of human life that you should leverage upon in promoting your work.

Do you feel that the public is aware of this, are we still too narrow when we see art as only the finished product and not the ideas and philosophies behind it?

No, I don’t think so. Hopefully, this new generation is taking that approach, but my generation had a different interpretation, a different reading, of what art was and still is. I remember when I was a fresh graduate and had to go to the bank to open an account, I faced an interesting misconception from the teller. When you fill-up the form, you need to disclose your occupation, in which I wrote “Artist”. As I handed the form to the cashier, he asked me this peculiar question: “Dah berapa dah dik?”.

He thought I was a musician. These forms of misconceptions are nothing new. But I feel that things are currently getting better. We need to remove this stigma that artists also need an immense source of talent propagated by sayings such as “darah seni mengalir di dalam jiwa” which I find to be untrue. Art is a discipline, just like any other discipline. Anyone can be an artist if they learn, and put enough work into the interest. Maybe I say that because I am a teacher, but it’s an acquired skill, just like any other skill. The gift of art-making doesn’t just drop from the sky.

You’ve been talking about how there is a generational difference in how we view art. Do you believe, as someone who has lived through the 80s and 90s, that there was a sense of freedom in local fashion and pop culture then? How do current times compare?

Those times were obviously different. Even though it was not so long ago, there were different perceptions of how we viewed things. One of the most glaring differences that I can see has a lot to do with culture and the current political situation, such as the national policies that were pushed forth within that time. When I was growing up as an art student, we were in the midst of finding a blueprint for a national identity. We were asking ourselves “What is a Malaysian identity?”. We know a lot about Chinese and Japanese art, but what is Malaysian art? So, we tried to formulate and look for the ingredients for national vernacular within our work. And I remember during my final year in Malaysia, we were banned from doing figurative drawings as it was condemned to be “not in line with our culture”.

We needed to assimilate some form of Malay, Chinese, or Indian identity – that was the formula. And I feel like it didn’t work because you cannot enforce these policies overnight. But that was the period that I’ve gone through. But after that, in the early 80s and 90s, came another wave within the art industry. Islamisation became the core to which we had to be aligned. That was another phenomenon. I consider myself a guinea pig, having lived through the 80s to the 21st century, and I find that who I am today is a concoction of those distinct periods. But that is not necessarily a bad thing. It makes you know who you are, and it brings in resilience, where you become more adaptable to rapidly changing times and policies.

I believe that art circles now are more aware of how it can be linked to the public – where art can be accessible, rather than viewing art as a mechanism to promote and consolidate a sense of identity. It is no longer about how we present Malay, Chinese, or Indian art, but how do we involve the community with what we do?

You mentioned about the surge of Islamic values and ideals that overlayed guidelines within Malaysian art. Do you believe that this period brought forth a sense of identity divide for Malay Muslims?

That is quite an interesting angle. Back to when I was in my final year, we were banned from doing figurative art. But in fine art, it is necessary for you to understand the anatomy of figures. After my time in UiTM, I was accepted into the Slade School of Fine Art at the University College of London. And I remember that my first encounter with a figure was a nude. I was so shocked at the experience of witnessing a nude, not knowing how to react – “berdosa ke?” [is it sinful?], “Should I not see ke?”, or “Should I just drop out of the class?”. But the more I thought about it, I realised that I just had to look at it as a form of knowledge. I took to it that the more you understood the figure, the more you understood creation. So, it depends on how you assess these types of situations. It is irrational to me how one can set up barriers to garnering knowledge. I studied nude figures for two years, and the more I looked at it, the more appreciative I became, of how there are universal proportions between the head and the body, how the length of your legs is proportioned to that of your torso, as if you’re a doctor studying anatomy.

So back to your question as to whether I faced a conflicting period: yes, in a sense, but at the end of the day, you have to assess things for yourself. It is all about the “niat” [intentions] behind your search for knowledge. I lived through a time when strict legislation was imposed upon me, restricting the avenues I could take to express myself. I was told that certain forms of expression would bring me to hell. I don’t think that is how it should be. What we need are deeper discourses that penetrate beyond the surface, toward the core of our intentions behind what we do.

But it was also good that I had a strong connection to my Malay identity. I was raised in a kampung [village] and was taught from an early age on certain values, mainly, respect. And I feel like these lessons should be encouraged. It should be embedded in you and expressed in your art, rather than being imposed upon you unwillingly by an authority.

Due to the strict enforcement of laws during that time, were artists finding solace in new alternative mediums that were in line with the current rules?

I don’t think so. When they banned “Mak Yong” in Kelantan, it was sad to see that our culture was being dismissed right in front of our very eyes due to certain beliefs. I think there was a lack of understanding and knowledge among scholars. So that’s the important thing about knowledge: having too little of it can be very dangerous. We need to always be open to discourse, and settling issues through “musyawarah” [council] is ideal. But back to your question, I don’t think there were any alternatives, I didn’t see anyone removing themselves from the restrictions. I think people were just finding their own way within those restrictions.

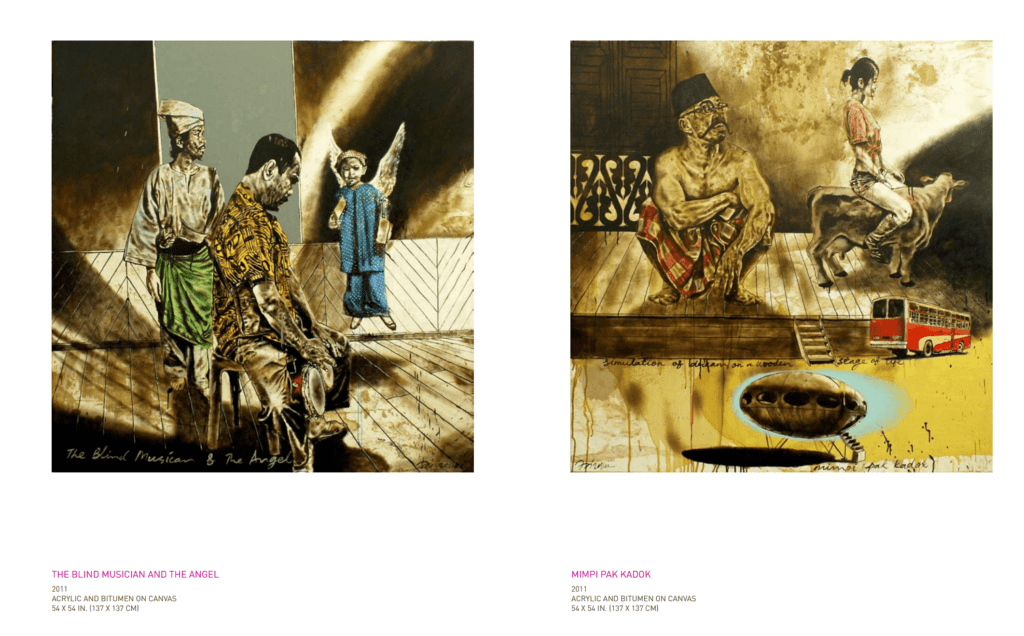

Something interesting that I have always experienced is people asking me: “How Malay is your art, Jai?”. I don’t think that I need to paint a “kain pelikat” [sarong], or a “wau bulan” [moon-shaped kite] to prove my ethnicity. It is the process of my art-making that I believe expresses that part of my sense of self. When I walk into the studio, I walk on the floor barefoot, I regard the floor as a sacred place, sharing that Malay belief of “gelanggang” [court]. And I feel that that is enough for me to pay homage to who I am. I do not need to explicitly show my Malay-ness through the products of my art. It’s all about the consciousness behind your work. I enter the studio with a “bismillah” and I feel that is enough for me.

Going back to your Malay identity in your art, we would like to talk about some of the work that you have done, such as “Mantra” and your recent “Cerpan Cerpen”. We see that it involves many local, familiar imagery. Do you believe that more artists should strive towards a Malaysian visual vernacular that can incorporate our individuality as a nation? To make art more inclusive and representative of who we are.

I think that when you apply your artmaking, you automatically tune into your roots. I had a solo in New York where I was thinking about what to put up. I felt that abstract and contemporary works were in abundance during that time. So, I had a strategy to showcase my local element. I took photos from our local Malaysian streets and markets and made those ingredients for my art. There was a particular piece of mine that depicted the slaughter of a cow during Hari Raya Korban. That caught the attention and fury of those in New York. But what they failed to understand is that we view these practices within a different context. I had to explain to them that we slaughtered these animals to give to the poor.

That was the concept. And that is what I feel excites me to add local ingredients into my work – it acts as an opportunity to spark discourse and discussion with others. In a way, you become an ambassador for your culture and your beliefs for your audience. So, going back to the question, I feel that the best part of showcasing your art occurs when you integrate a sense of your identity and culture within your works. Because, though the role of art has changed throughout the ages, what maintains is that at its crux, it reflects who you are and your origins.

In your personal experience, do you believe that some artists throughout their art-making journey lose their sense of self due to an excessive need to make sure that viewers understand the messages and themes that they are trying to project?

I wouldn’t call it losing your sense of self. You may lose your sense of integrity and your sense of purpose as you try to please other people. I think it goes back to your purpose, your “niat”. What is it that you’re looking for? Are you looking for recognition and validation from others? Or are you looking at telling the truth about your art? I think those are two different things. It happens at times when artists compromise their work to send it off to a gallery. You have to remember that certain works have a higher commercial value than others. Sometimes you’d like to make something that you like but it cannot sell, and due to the need for sustenance, you’re supposed to temporarily utilise other forms or mediums of art. And we can’t say that because of it you lose integrity. We as humans need to do what we must to survive. So, think of it like this – you make art to make money so you can sustain the profession that you love. Still-Alive artworks are very sellable, and sometimes artists make still lifers in order to support their other forms of art. I don’t think that is much of an issue. I feel that a lot of younger artists have this issue, as their works need to be approved by a gallery so that they can showcase their art in hopes of making a name for themselves in the future. It’s an interesting twist – you make money from your work, but you do not work for the money.

But when you try too hard to validate yourself amongst others, I think that becomes an issue in trying to tell the truth about who you are.

Should viewers be given the freedom to interpret art? How would you then define art? Is it bestowed on the eyes of the viewer or the artist?

It becomes hard when you get too stuck on definitions. Art does not need defining. Interpretations should be left to be vast and open. If I draw a flower and you see a monkey from it, who is to blame? You have the right to make your own interpretations, I can only suggest and give hints on what I am trying to present.

Let’s take this analogy: Music is suddenly being played, and you find yourself shaking your legs to its rhythm, but you don’t know what it’s about. And sometimes you hear something that you just hate without knowing its meaning. It’s really about how that piece of art makes you feel at that certain point in time. However, if you try too hard to understand what that piece means you still wouldn’t get it. That’s when the doors for interpretation start to close. So always have an open mindset when it comes to art. For me, it’s so rewarding when people react to your art. And when I mean react, I don’t mean like – like and dislike are reactions. It’s good when you’ve garnered a response from your viewers. So, don’t take only the good responses, negative pulak tak boleh. That’s not fair.

And what about artists who make art that is consciously made to be hated? Can we disqualify that? Remember that it is not always about the beauty, it can also be provocative, forcing you to put thought into it.

What advice can you give to those who find it difficult to emote themselves?

I’ll tell them what I always tell my students. I understand that now is a challenging time, especially for young artists. You have art that you cannot show, you have galleries but are unable to invite everybody to come. What’s the point of having only 50 people at an opening? You need to make your openings as big as you can. And because of this, I can understand that young upcoming artists might feel discouraged and unmotivated to continue on their creative paths. But we must also take advantage of this. If you think about, with the restrictions imposing a maximum of 50 people to galleries, bigger artists won’t be interested in showing their pieces during these times. So now they are looking for upcoming artists to fill in their spaces to get an audience. Take advantage of that while you can. Start preparing your portfolios and online promotions.

Understand that God works in mysterious ways. Even if you see things from a negative viewpoint, there might be positive elements embedded within it. I recently read a book about the power of bad, and how bad situations can empower you through difficult times. To be fair, bad impressions tend to last longer than good ones. But if you let bad impressions govern you, you’ll find it difficult to accept how things are. So, take advantage of bad situations by finding out the ways in which they can benefit you.

What about those who would like to pursue art but are facing challenges (financial, personal, etc.) in reaching that goal?

I have young artists who are working in odd jobs. Making art is not your job, it is a hobby that you do on your own time. Make the money to make art. And make it through all means, Work, unless if you’re an established artist. But at this stage, work hard to get the provisions to support your art. It also teaches you to be more flexible and versatile, to persevere through situations in order to do what you love. That would make you a better artist, I am sure, even a better human being.

Photographs by Pravin Nair & Kelly Lim