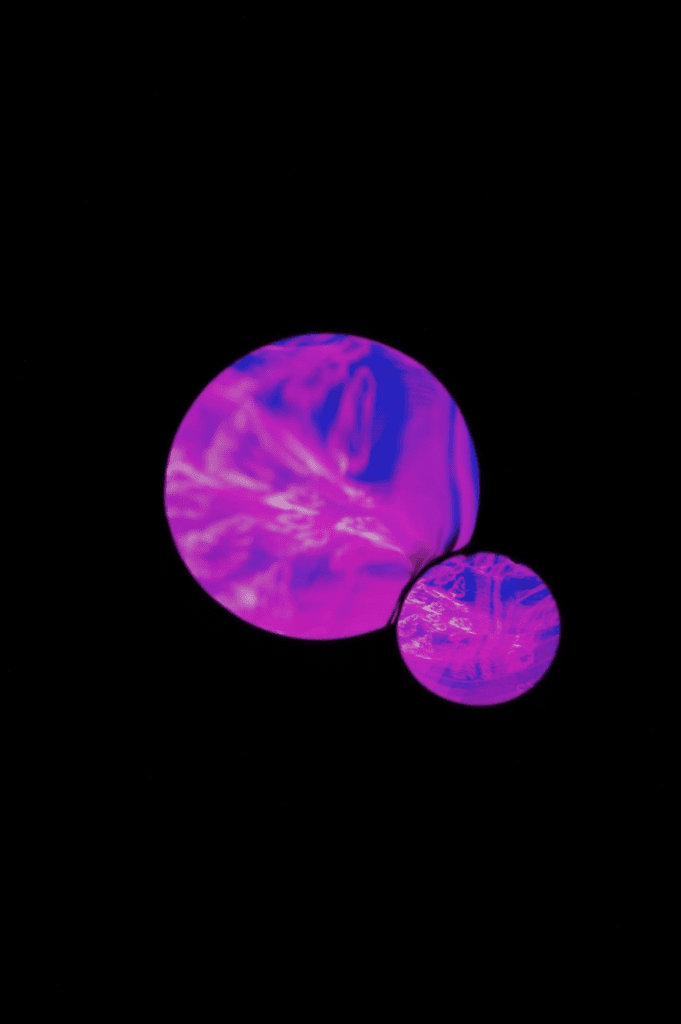

Yet it was this ambiguity that I felt maintained the gaze of the observer, for we dare not move our eyes away, all in hopes of finding a better interpretation in deciphering its meaning and intentions, for it leaves you never truly satisfied with what you come up with. Almost like an inviting wave, it makes you want to know more. It also had this almost mystical tendency, amidst your pondering, of swallowing you whole within its darkness, entranced, the bright circles acting like portals to some foreign dimension that I found incomprehensible yet still infinitely intriguing. Curiosity later turned into an awestruck wonder that simply took over the body; an appreciation for a work of art simply for what it is and its capacity to invoke certain feelings and movements inwards, regardless of its intentions. ‘Isn’t that what art is all about?’ I recalled asking myself. Having the opportunity to soon interview her on the piece, I knew the conservation was bound to take on interesting twists and turns.

While speaking to Mariame, my initial curiosities began peeling away as I was provided with her intention and contexts, much like how one leads the blind (yet in this case, however, somewhat paradoxically, the latter is a very much sighted yet unknowing observer). It was interesting to hear how she wanted to portray an unconventional image of Lyon that seemed to transcend spatial and temporal boundaries, by creating a rather unusual juxtaposition of the new with the old. This was done by editing a digitalized archive of a 19th-century topographical map of the city with a 3D computing software called Blender. To her, it seemed to reconcile awareness of the developments and urbanisation that subjected the city to rapid changes and shifts, an epiphany sparked by the transformation of the hospital she was born in into a luxury hotel and commercial centre. It would be wrong, however, to interpret this piece as reflecting a nostalgic longing for the resurgence of the past, she exclaims, for it was more an embracement of the changes that are part and parcel of modernity. It was therefore not a love letter to what Lyon was, but an invitation and reflection to what it could be. Yet the intentions of these developments did not go unquestioned, as she reflected upon the replacement of buildings like those of a hospital that provides a social benefit with commercial hubs that were built to fulfill desires of a more individualistic nature.

With myself satisfied as to the pieces of the puzzle finally came together to form a coherent understanding of the artwork, I should have felt at ease. Yet that was certainly not the case. As our conversation ventured deeper into her work, new and much more abstract interests, and curiosities began to reopen the void of knowledge that still lay prevalent within my mind. For I came to know that her work resonated less with the ‘finished’ product that I have grown to become comfortable with (known simply as Experimentation #12), and more towards the processes that have led to what is arguably its final end result. Here, its name bore the clue to a set of preceding experimentations that were not necessarily about Lyon. Rather, the transformation and the development of the city are embodied within the artist’s innovative take on photography that seeks to challenge earlier writings and scholarship on the theories and definitions that made up the now anachronistic yet fascinating world of analogue photography. By consciously contradicting the assumption and theories of earlier scholarship laid the artist’s desire to represent the highly contingent nature of our lives- that what it is is simply what we make of it, and therefore precedent upon the environment and context that we find ourselves in. It seems to push against the notion of a positivist and objective reality, cynical in how it puts into question the principles and ideals that we hold dearly in our hearts and minds. What was then termed absolute and objective understanding of ‘the photo’ by scholars like Rosalind Krauss and Alfred Stieglitz were now put into question by developments within digital photography.

Done skillfully in numerous ways by the artist, what intrigued me most was her reinterpretation of the index and trace of a photo. She explains that in digital photography, complex algorithms have replaced light and shadow as its foundational aspect. This was interesting as it represented the photo as a physical product with a non-physical element, and puts into perspective the role of the artificial and virtual within our material realities. Her usage of mirrors, reflections, and projections seem to express this, where she claims that ‘the virtual space created on the blender is doubled with its reflection on the virtual space of the mirror in the photographic field’. Lurking back to the constructivist nature of our visual reality, the composition of the projected images seen on the black backdrop can be easily altered in accordance to the position of the mirrors, leaving it with a sense of fragility due to its susceptibility in being ‘broken’ and rearranged.

Yet, upon individual reflection, I realised: aren’t photos themselves a construction? Aren’t they fragments that are skillfully selected by the photographer to wholly represent a certain time and space to evoke certain emotions and memories? Like ourselves, our perception of life and our history as a species (which has become increasingly visual) are mortal. They are subject to decay and demise and can constantly be replaced. Photography is also highly individualistic, for it portrays a multitude of meanings that are subject to change with individual imaginations and ideas of a time and space that once was. Paradoxically, it is then also infinite, for it can transcend the limitations of human life expectancies and maintain a relevance that can stretch for generations due to its versatility. I now think of the photos that lay around my room and question what they mean to another, ‘What feelings do they evoke?’ ‘What memories do they put in motion?’ ‘How different are they to mine?’ and ‘How much will my own perception change with time?’. Photos that are now no longer interesting merely for their subject matter but the debates and questions that they present underneath their glossy surfaces. In conclusion, Mariame Ahmad’s Experimentations is an amazing work of art, for I believe that the best are ones that keep you questioning.